Why do restaurants serve so much food in tasting menus?

I still recall the 'Oysters and Pearls,' a dish that featured a 'sabayon' made from pearl tapioca paired with oysters and caviar.

It was one of many flawless creations from Thomas Keller, and they just kept coming.

I was thrilled to be dining at Per Se that evening in 2004, only a few months after Thomas Keller and his partner Laura Cunningham opened their East Coast restaurant in the Time Warner Center in Manhattan.

There was no conventional appetizer, entrée, or dessert. It was the ultimate tasting menu, I thought, perfectly curated by Keller, Cunningham, and their team.

True to its fine dining status, the atmosphere overlooking Columbus Circle was refined and serene, and the service was impeccable. (The staff had taken movement classes to master walking gracefully through the space.)

As for the food? I lost count of the more than a dozen exquisite dishes served throughout the evening, and it lasted well into the night.

Yet, at times, it felt like an endurance challenge for my stomach.

Demonstrating a chef’s artistry

Typically found in cities where dining is a major cultural focus and where people have significant disposable income, tasting menus are often associated with affluent diners willing to spend hundreds or even thousands of dollars on three-hour meals entirely curated by the chef.

For chefs, tasting menus offer a chance to be inventive with a range of dishes and showcase their culinary expertise.

“Thomas Keller is at the forefront of this movement,” says restaurant consultant Clark Wolf, who has worked with restaurants across New York City, Las Vegas, and throughout the United States.

“His approach has always been to create a small dish that’s just one or two bites — enough to capture the essence of what’s being offered, but not so much that it overwhelms your ability to move on to the next course.”

Our taste buds are more inclined toward smaller plates

In an ideal world, tasting menus would align perfectly with the human palate.

That’s because humans often experience 'palate fatigue' after just three or four bites, explains food historian Beth Forrest, a professor at the Culinary Institute of America’s New York campus.

In essence, our taste buds grow tired. “But if you stop right at the point when people are truly enjoying the food, their memory of it will be far more satisfying,” she adds.

However, when taken to extremes, the experience can become overwhelming – a display of dominance by mostly male chefs “trying to force the diner into submission,” says Wolf. “That’s just forced feeding.”

(Keller faced criticism in a 2016 review by New York Times dining critic Pete Wells, who lambasted the renowned chef’s staff for becoming careless and downgraded his restaurant from four to two stars.)

Even farm-to-table pioneer Alice Waters has grown weary of them.

While Waters can recall the legendary, extensive tasting menus from her youth, she’s become less enthusiastic about them as she’s aged.

“I always feel like when the portions are small, it’s just too much and drags on too long,” says Waters, the founder of Chez Panisse in Berkeley, California, known for its three-course prix fixe menu.

This is not the same as Japanese omakase

While many Western tasting menus are inspired by Japanese omakase, they are distinct creations, says Greg de St. Maurice, a culinary research fellow at the University of Toronto.

Omakase originates from the sushi tradition, which is typically ordered a la carte. By choosing omakase, diners are allowing the chef to select the freshest, in-season ingredients, explains de St. Maurice, a scholar of Japanese cuisine.

Even at high-end restaurants in Japan – some of which have been around for centuries – diners often don’t see a menu, says de St. Maurice. They trust the chef’s judgment. (This, however, is not omakase.)

“It’s assumed that the chef will serve what’s in season and freshest. This mindset is a very different starting point compared to Western tasting menus.”

A Western tasting menu “feels more like a chef’s greatest hits, while omakase is about what’s in season and what’s spontaneously available,” he adds.

The evolution of the Western tasting menu

While modern tasting menus likely originated in the 1960s, the concept of multicourse meals in the West dates back to the 19th century, and even earlier, according to food historian Forrest.

“If you look even further back to medieval times, you’ll find large courses with as many as 25 dishes per course,” she explains. “The spectacle was created by the sheer number of plates served at once.”

The 20th century saw the rise of celebrity chefs preparing tasting menus, beginning with French chefs such as Paul Bocuse, Alain Chapel, Michel Guérard, and the Troisgros brothers. They pioneered smaller portions and menus with six to eight courses, says Forrest.

“It wasn’t until the late 1980s that we saw an explosion in the number of courses, with menus featuring not just nine, but sometimes 20 or more courses,” she adds. “It became a clear symbol of status and wealth, whether economic, cultural, or social.”

They thrive in major, food-centric cities like New York and San Francisco, where there’s a large population of residents and visitors – including Wall Street and tech moguls – willing to indulge in extravagant meals that last for hours.

Fine dining as performance art

For some of the most influential and affluent diners, it’s a curious decision to relinquish control and allow a chef to decide every aspect of their meal.

Renowned for his unique approach to foie gras, a visit to Ko last year showcased Gray’s food as entertainment, much like Wells described in a 2015 review.

A chef grates a “frozen cured brick of foie gras over a Microplane held above a bowl filled with pine nut brittle, Riesling jelly, and lychee, scattering delicate pink flakes of culinary magic,” writes Wells.

At Blanca, hidden behind Roberta’s in Brooklyn, diners at one of two seatings gather around a bar to watch the culinary team prepare and serve each dish simultaneously. It’s a performance, with Chef Carlo Mirarchi and his team taking center stage.

“It’s not just about the dish you’re eating, but the entire experience — the dishes before and after it too,” Mirarchi explained. “There’s a rhythm, an ebb and flow, not just a peak and a finish.”

“We enjoy experimenting with temperature contrasts to keep guests from experiencing palate fatigue. And when it comes to the food itself, it’s about discovering a unique ingredient and showcasing its finest expression.”

The small plates are flawless. Yet, as the courses progress, the portions seem to grow larger — a more American style perhaps — culminating in a large piece of freshly baked bread. The temptation to finish it, warm and inviting, makes it nearly impossible to continue.

A true sampling of the entire experience

In cities with a lively dining scene, where patrons don’t want to spend excessive time or money on a regular meal, the American tasting menu has adapted to a more approachable size.

Empire State South in Atlanta offers a six-course tasting menu in addition to its regular options.

While it’s listed online, the tasting menu isn’t on the printed menu, so regulars typically book it ahead of time. Occasionally, servers recommend it to guests who are unsure and want to sample a bit of everything.

Launched in 2011 by former executive chef Ryan Smith, who is now at Staplehouse in Atlanta, the abbreviated tasting menu highlights the chef’s technical skill, inquisitive nature, and inventive flair.

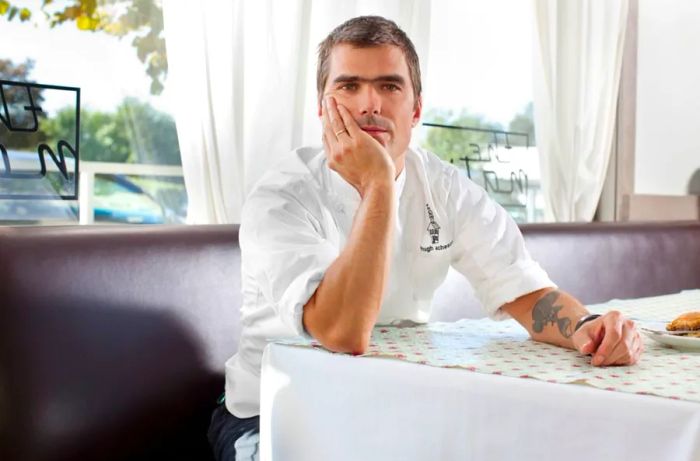

“It’s sometimes made up of dishes from the regular menu, and other times it includes new creations or ideas Josh is experimenting with,” explains chef/owner Hugh Acheson. “It’s always a demonstration of technique and the current culinary direction we’re passionate about.”

“Occasionally, it features dishes we plan for the future, or we might alter a dish to explore a different flavor profile or experiment with a new taste,” notes executive chef Josh Hopkins, who left the restaurant in late April.

Every day, Hopkins would arrive at the restaurant, assess the menu, and adjust the dishes based on the fresh ingredients or new concepts he wanted to incorporate. If a tasting menu was booked, he might even modify a recipe to offer guests something uniquely special.

“There’s something a bit magical about a multi-course dinner – the variety, the surprises along the way, and the opportunity it gives our team to practice professionalism in a fresh context,” says Acheson.

Empire State adapts its tasting menu to accommodate various dietary needs, from allergies to vegetarian preferences, by modifying dishes from the printed menu.

As long as everyone at the table opts for the tasting menu, dietary restrictions are never an issue, says Hopkins. “We can always accommodate those needs.”

Despite its appeal, Empire State’s tasting menu isn’t enough to sustain the business. While it’s popular for celebrations and business dinners, many guests still prefer traditional meat, cheese, and vegetable dishes paired with drinks, or additional vegetable-forward plates.

Even Alice Waters has expanded with a cafe addition to her iconic restaurant.

At Empire State South, offering diners a range of options isn’t just a possibility, it’s a key feature.

Alice Waters, the founder of Chez Panisse, acknowledges that her renowned farm-to-table restaurant has had to adapt over time.

Chez Panisse, which opened its doors in 1971 when Waters was just 27, has always offered a fixed-price menu. In 1980, she expanded by opening an upstairs café, giving guests more flexibility in their dining choices.

At the café, patrons can choose from a menu featuring fresh, seasonal dishes prepared in the classic Chez Panisse style – a place where chefs are trained, inspired, and eventually branch out to create their own restaurants.

Momofuku Ko, the exclusive tasting menu-only venue in Manhattan, has recently introduced an à la carte option in its newly expanded bar area. Per Se, on the other hand, continues to offer a five-course tasting menu in its elegant salon setting.

Does the tasting menu still hold its relevance today?

As the iconic restaurant marks its 47th anniversary, Waters and her team are reflecting on whether the tasting menu still remains a key part of their culinary identity.

'I've been reflecting on this a lot,' says Waters.

'Without the café upstairs, accommodating guests with various food allergies and preferences would be much harder,' she explains. 'That’s the biggest challenge to the tasting menu, besides the cost.'

'I enjoy offering people things they might never have chosen on their own, like mulberry ice cream. Because it's part of the fixed-price menu, they try it and end up loving it. That’s what excites me.'

'I don’t want the experience to feel elitist or hard to understand,' she says. 'It should just be a joyful experience. Plus, at this stage in my life, I can’t handle large portions of complicated dishes.'

'I'm less interested in complex techniques than I am in experiencing a new flavor, like a berry I’ve never tasted before.'

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5