A Quiet Olive Oil Revolution Is Unfolding in Tunisia

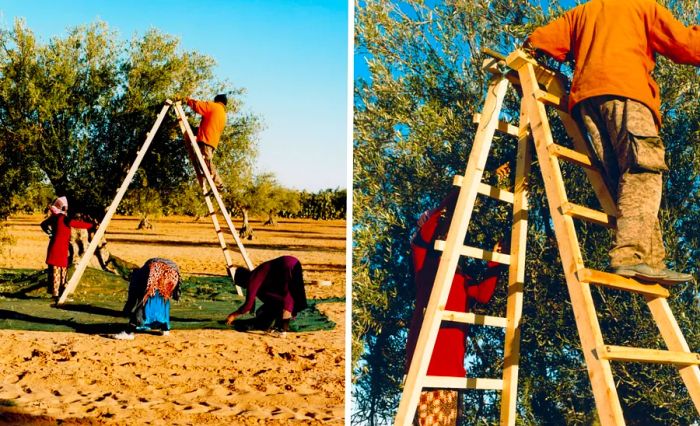

As November begins and olives shift from green to purple, Sarah Ben Romdane and her team of nearly 50 women farmworkers set out. Under the warm glow of a Bou Thadi sky, they divide into groups, meticulously working tree by tree—planted at the same distance apart as the Romans did centuries ago. They use small hand rakes to gently coax the olives from their branches, letting them fall onto large nets below.

While they work, the women sing timeless songs passed down through generations. The lyrics express, “I have a garden of black olives, beautiful ladies come to harvest it.” As they gather the olives, the melody softens, and they transport the harvest to the mill for cold-pressing, ensuring quality and flavor are preserved.

Photos by Ilyes Griyeb

“Many people think olive oil primarily comes from Italy, Spain, or Greece, and that’s the end of the story. They have no idea that Tunisia ranks as the world’s third-largest exporter, the top outside of the E.U.,” says Ben Romdane, a 29-year-old entrepreneur who divides her time between Paris and Mahdia, a coastal town about 60 miles northeast of Bou Thadi. “In reality, they know very little about Tunisia.”

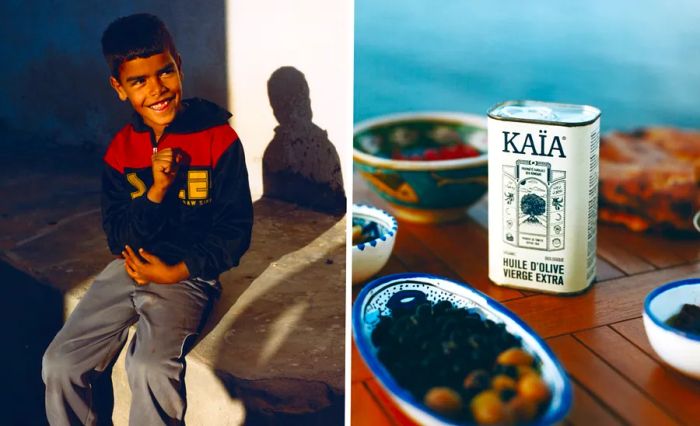

Picture yourself browsing the aisles of your local grocery store for a new olive oil. The labels may suggest the oil is entirely Italian, but a closer look at the fine print reveals more: Pressed in Italy, Produced Outside the European Union. And that’s assuming the bottles even clarify that detail. Ben Romdane, who distributes Kaïa, her own brand of organic extra virgin olive oil crafted from heirloom olives handpicked on her family’s fifth-generation estate, is part of a rising movement to promote high-quality, artisanal Tunisian oils. With one foot in Tunisia and the other in Europe, she has become a natural ambassador for this transformation.

Photo by Ilyes Griyeb

I aim to demonstrate that small producers can create an alternative system that prioritizes the quality of olives and honors the people who work with us while safeguarding our land.

For millennia, North African countries have cultivated olive trees and produced olive products. Researchers trace the cultivation of the olive tree back to the Phoenicians, who began spreading it across the Mediterranean through trade around the 10th century B.C.E., soon producing oil in Tunisia. The country’s sun-soaked, semi-arid landscapes provide ideal conditions for olive cultivation, fostering a thriving global industry. Consequently, olive groves encompass approximately one-third of Tunisia’s total land area, with olive oil making up nearly half of its agricultural exports.

Photos by Ilyes Griyeb

Similar to wine merchants who source grapes or finished wines from various producers to bottle under their own label, the global olive oil market has long traded in bulk olives, often relying on cost-effective production in countries like Tunisia. “Quality was often overlooked for many years,” notes Sonda Laroussi, an engineer, olive oil consultant, and professional taster based in Sfax, Tunisia. “Producing and marketing a high-quality product with complex aromas requires superior machinery and expertise, which comes at a price. If profit margins are slim, the prevailing thought is: Why bother?”

Nevertheless, Tunisian olives possess remarkable character. The two primary varietals used for oil are Chetoui and Chemlali, both rich in antioxidant-packed polyphenols, offering distinct flavor profiles. Chemlali, the heirloom variety cultivated on Ben Romdane’s family estate, constitutes 70 percent of the olives produced in the country. It yields an oil that is smooth and versatile, low in acidity, and harmonized with notes of almond and artichoke, culminating in a peppery finish.

Photos by Ilyes Griyeb

A key motivation for Ben Romdane is to honor and raise awareness of the country's rich terroir. Raised in Paris by Syrian and Tunisian parents, she spent her childhood summers in Mahdia, just a short drive from three olive estates with a lineage spanning five generations. Her great-great-grandfather, Mohamed Romdane, was the first Tunisian to export local olive oil to the United States, where it earned accolades. The family business continued until the 1950s.

In the summer of 2020, Ben Romdane left Paris to join her parents in Mahdia, expecting to return quickly to her life as a culture journalist. However, she reconnected with her heritage during a time of global uncertainty, gaining a fresh perspective on life. With her family’s support, she purchased olives from the estate in November 2020, preparing to bottle and globally market the oil under the name Kaïa, a Product of Tunisia.

Her second batch caught the attention of specialty retailers like La Grande Épicerie in Paris and Sabah in New York City. “We seek the trifecta: an exceptional product, stunning packaging, and a compelling backstory,” explains Clémence Le Tannou, the buyer for La Grande Épicerie, who introduced the brand—its first Tunisian olive oil—onto its shelves. “Kaïa had it all, plus a distinct character compared to our other oils. Sarah's presence in-store for tastings allowed our regular customers to instantly connect.”

Photo by Ilyes Griyeb

By establishing a direct supply chain that allows her to oversee every aspect of production and provide fair wages for workers, Ben Romdane aims to use heirloom agriculture as a form of cultural and political resistance: “The existing trade system perpetuates a cycle that damages the reputation of ‘Made in Tunisia.’ I want to demonstrate that small producers can create an alternative model that honors the quality of the olives and respects those who labor and protect our land.”

Ben Romdane's vision is shared by other Tunisian olive oil producers. Slim Fendri of Domaine Fendri and sisters Afet and Sélim Ben Hamouda, who revitalized their family farm in 2015 to launch A&S extra virgin olive oil in 2017, have also received prestigious awards at NYIOOC, the renowned global olive oil competition. The benefits of such recognition can be immediate, Afet notes. “We face tough competition from European producers with better infrastructure. However, contests raise our profile, and consumers begin to take notice.” She believes that spreading awareness of Tunisian olive oil beyond these competitions is just a matter of time.

Photos by Ilyes Griyeb

Tunisia's ambitions are on a tight timeline. In 2020, the country exported 27,000 metric tons of bottled olive oil. The target, as stated by Chihab Ben Slama, president of the Tunisian Chamber of Olive Oil Exporters, is to reach 70,000 metric tons by 2025.

With only 5.5 metric tons produced from her 2021 harvest, Ben Romdane is still a relatively small contributor. However, her dedication is evident. “A nation is empowered when it understands its culture and shines,” she asserts. “This is my way of reviving that pride for our people.”

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5