A Tulsa Writer Contemplates His City's Efforts to Honor the Legacy of the Tulsa Race Massacre Responsibly

Crowds gather at the Black Wall Street mural situated in Tulsa’s Greenwood district.

Photo: Shane Bevel

Crowds gather at the Black Wall Street mural situated in Tulsa’s Greenwood district.

Photo: Shane BevelIn Tulsa, we take pride in claiming remarkable Black individuals. John Hope Franklin exemplifies this, despite not being born here and spending only a brief time in the city. For many, Franklin stands as the greatest figure Tulsa has ever produced. He graduated as valedictorian from the city’s segregated Booker T. Washington High School at just 16 years old in 1931 and became the first Black individual to hold a full professorship at a predominantly white university (Brooklyn College, where he led the history department). Yet, for me, a Black man raised in this Oklahoma city, he is someone who only lived here as a teenager for six years before departing.

As the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre approached last June, I reflected deeply on Franklin, his legacy, and the significance of remembering a tragedy. During the summer months, I explored the monuments, exhibitions, and galleries—many bearing Franklin’s name—curated by the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, established to honor that tragic event. What I discovered was a city, my city, caught in a tension between the desire to remember and the unwillingness to achieve genuine reconciliation.

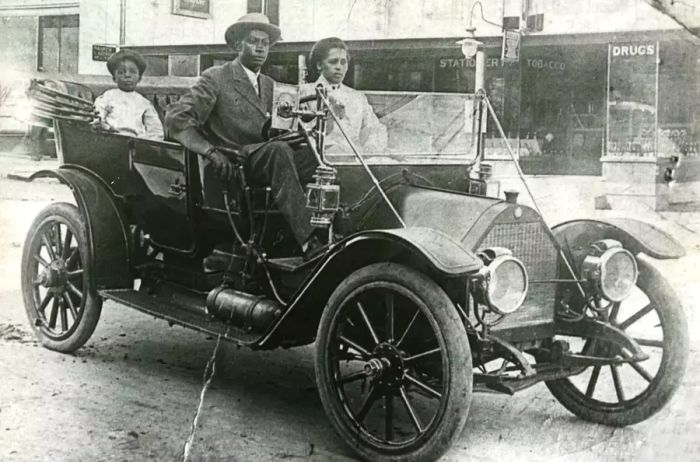

This image features John Wesley Williams, Loula Cotten Williams, and their son, William Danforth Williams. The family was the proud owner of the Williams Dreamland Theatre, which was tragically destroyed during the massacre. Source: Tulsa Historical Society & Museum

This image features John Wesley Williams, Loula Cotten Williams, and their son, William Danforth Williams. The family was the proud owner of the Williams Dreamland Theatre, which was tragically destroyed during the massacre. Source: Tulsa Historical Society & MuseumIn the early 1900s, the all-Black Greenwood district in northern Tulsa thrived, often hailed as 'Black Wall Street.' This vibrant community spanned 35 square blocks and operated as a self-sufficient Black society, complete with its own shops, grocery stores, doctors, lawyers, schools, and entertainment venues such as the Williams Dreamland Theatre, which showcased live performances and silent films. Greenwood also had its own newspapers, including the influential *Tulsa Star*, edited and published by A.J. Smitherman, a prominent Black man.

On May 30, 1921, a white mob gathered in response to the accusation against Dick Rowland, a Black 19-year-old shoeshiner, who was said to have assaulted Sarah Page, a white 17-year-old elevator operator. By June 2, after the flames were finally extinguished, a significant hub of Black entrepreneurship in America was obliterated: 600 Black-owned businesses, including the *Tulsa Star* offices and the Dreamland Theatre, were destroyed, leaving nearly 10,000 Black Tulsans homeless and claiming an estimated 300 lives.

Today, the only remnants of those businesses are the plaques embedded in the sidewalks along Greenwood Avenue, marking what once thrived there. Visitors can find these plaques by following the newly established Pathway to Hope, which leads to the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park. This pathway runs alongside Interstate 244, which bisects the historic Greenwood district. Last June, I walked the entire length of this pathway, observing the many plaques as vehicles zoomed past overhead. The walkway, adorned with benches and quotes from Franklin, Maya Angelou, and Toni Morrison, culminates at the recently built history center, *Greenwood Rising*.

An image showcasing the Greenwood Rising history center. Photo by Melissa Lukenbaugh/Courtesy of Selser Schaefer Architects.

An image showcasing the Greenwood Rising history center. Photo by Melissa Lukenbaugh/Courtesy of Selser Schaefer Architects.The exhibits detail the history of Greenwood's development and include a reenactment of the violence through first-person narratives. They depict the massacre as a historical event while emphasizing a model of reconciliation that, in my view, Tulsa has yet to realize. I left with the thought, *This might appeal to white audiences, but it doesn’t resonate with me.*

On June 5, just days after the centennial of the massacre, I found myself seated in the *BOK Center*, situated in the heart of modern downtown Tulsa, about ten blocks from Greenwood. I was there to see Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra perform *All Rise: Symphony No. 1*. It was my first experience witnessing Marsalis live, and I was unfamiliar with this particular piece. The music struck a deeply emotional chord, and I appreciated the presence of the multidenominational Tulsa Symphony & Festival Chorus joining the orchestra. However, upon reading the program, I discovered that Marsalis had composed *All Rise* in 1999 after being commissioned by the New York Philharmonic to create a reflection on 20th-century music. I couldn't help but feel that the Centennial planners missed a vital opportunity to invite an artist of Marsalis's caliber to create a unique piece for Tulsa in response to an event of such profound significance as the Tulsa Race Massacre.

The Pathway to Hope stretches from the center of Greenwood to John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park. Photo by Michael Noble Jr.

The Pathway to Hope stretches from the center of Greenwood to John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park. Photo by Michael Noble Jr.I reflected on Franklin's passion for music; he was a teenage trumpet player and part of a marching band in the early 1930s. When he attended a concert at the Convention Hall (the equivalent of today's BOK Center), he had to sit in the segregated section. In 2021, I found myself watching an integrated orchestra perform pieces by a Black composer, and I managed to force a smile.

During the 1910s, the Stradford Hotel was a symbol of Black prosperity located at 301 North Greenwood Avenue. It was the largest hotel in America that was Black-owned, operated, and exclusively for Black guests, featuring 54 rooms, a gambling hall, a dining area, a saloon, and a venue for live performances. Tragically, it was burned down by white individuals during the massacre. However, a Black-led initiative aims to restore the legacy of the Stradford with plans for the opening of a new hotel named Stradford21 in North Tulsa in 2023.

I contemplated the significance of this as I checked into the *Tulsa Club Hotel* (rooms starting at $116), just a mile south of where the Stradford once stood. Designed by Tulsa architect Bruce Goff, this building was initially funded by the Tulsa Club and the all-white Tulsa Chamber of Commerce in 1927, six years after the massacre. It served as a hotel for sixty years before being abandoned from 1994 to 2013, during which it suffered three arson attacks in two weeks in 2010. Now, it's been revitalized into a stylish lodging option, complete with a bar, restaurant, and Art Deco lobby. Approaching the entrance, I was struck by the presence of a Black valet and another Black front desk staff member, both of whom were exceptionally kind. Upon checking in, I found it ironic that my assigned room was on the fourth floor, which had been devastated by one of the fires.

A holographic display brings the atmosphere of a barbershop to life at Greenwood Rising. Photo by Michael Noble Jr.

A holographic display brings the atmosphere of a barbershop to life at Greenwood Rising. Photo by Michael Noble Jr.Later, I noticed a poster outside *Silhouette Sneakers & Art* proclaiming BLACK LIVES MATTER, accompanied by another that stated SAY THEIR NAMES: TERENCE CRUTCHER, JOSHUA BARRE, JOSHUA HARVEY, all Black men who were killed by Tulsa law enforcement in the last five years. Inside the store, a few racks filled with T-shirts, hoodies, and jackets occupied the center of the shop, surrounded by a carefully arranged collection of high-end sneakers. One pair featured black tops with red soles and displayed Michael Jordan's legendary No. 23 on the heel. I leaned in to confirm my suspicion—they were indeed Air Jordans—and then glanced over at the clerk.

"Hey, are those the Retro 11 Breds?"

"Absolutely," the clerk replied.

"May I take a photo?"

"Do you want to?"

I snapped a photo of the sneaker along with the price tag on the sole: $190.

An olive-green jacket featuring 'GWD AVE' (short for Greenwood Avenue) in gold block letters on a patch caught my attention. The clerk emerged from behind the counter.

"That's the last one of those jackets," he informed me. "Just in case you were curious," he added.

"Are you really buying this in the summer?"

"Yeah, you know, people visiting from out of town? With the last two festivals? They kept coming back to buy things for their friends. Those jackets flew off the shelves!"

I snagged the last one on the rack, driven by a protective instinct for what felt like mine.

The front page of the white-owned Tulsa Daily World dated June 1, 1921. Source: Tulsa Historical Society & Museum.

The front page of the white-owned Tulsa Daily World dated June 1, 1921. Source: Tulsa Historical Society & Museum.*Tulsa '21! Black Wall Street,* a play at the *Tulsa Performing Arts Center*, beautifully conveyed our narratives. I adored this production because it didn't shy away from the harsh realities of the massacre or the ongoing victimization of Black individuals that followed. It delved into the core of the truth—not just what white audiences can handle.

My partner, Laurel, and I experienced this artistic production that beautifully retold our oral histories, highlighting our families' victories and fears, while addressing our ongoing struggle to reconcile the violence inflicted by white Tulsans on their Black neighbors, a century later. I was deeply moved to tears, grateful that someone in Tulsa had accurately captured our story and honored us.

When the performance concluded, Laurel proposed we cross the street to *Andolini's Pizzeria*, which I firmly believe serves the best slice in the world. We ordered two Tulsa Flags and a blonde ale from the local *Dead Armadillo Craft Brewery*. As I savored a few bites of my pepperoni slice and downed half a glass, Laurel gently rubbed my arm and took my hand.

"That play was beautifully complex, right?" she remarked.

I smiled and nodded in agreement. Black survivors in Tulsa are remarkable because we have to be. This is Tulsa: the city that shaped John Hope Franklin and placed a significant burden on its sons like me—to be exceptional or risk being forgotten.

This is my city, my home. I too attended Booker T. Washington High School and graduated from the University of Tulsa. I want others to learn from our history, but I also hope to see it better safeguarded. Responsibly honoring a tragedy means visiting the site, understanding the true narrative, and passing it on so future generations will avoid the unforgivable mistake of forgetting.

This story was originally published in the February 2022 edition of Dinogo, titled This Is Tulsa.

Evaluation :

5/5