An Odyssey Through Oman, Where Skyscrapers Are Banned and Warmth is Abundant

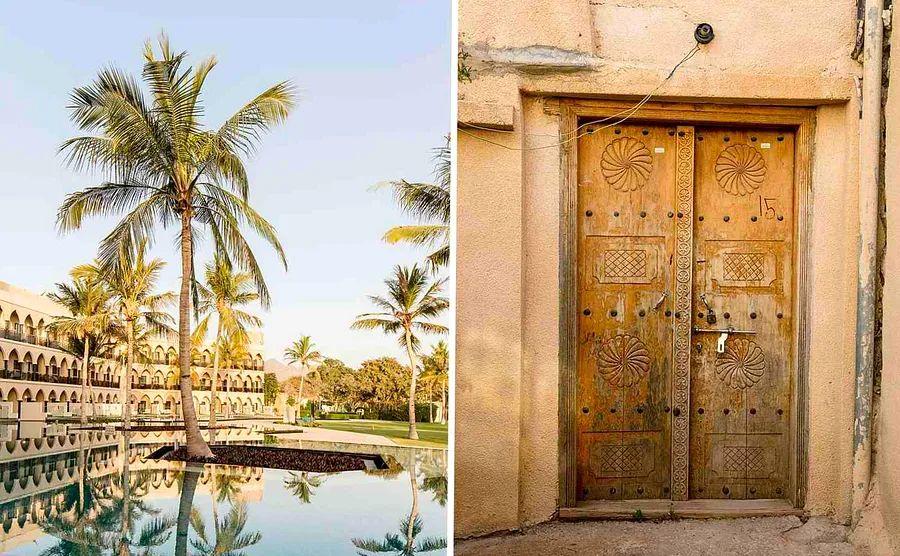

Left: Al Bustan Palace, a Ritz-Carlton hotel located in Muscat; the entrance of a house in a village near Jabal Akhdar, one of Oman's tallest mountains.

Photo: Stefan Ruiz

Left: Al Bustan Palace, a Ritz-Carlton hotel located in Muscat; the entrance of a house in a village near Jabal Akhdar, one of Oman's tallest mountains.

Photo: Stefan RuizWhen I shared my plans to visit Oman, a small nation by the Arabian Sea, most responses were puzzled looks. O-what? Where exactly is that? Is it safe? To be honest, despite my extensive travels in the Middle East, I knew very little about it myself. In a region marked by unrest, it stands as a serene refuge, and thus, isn't the kind of place that frequently makes headlines.

Naturally, that’s precisely why it deserves more attention. Alongside its red-sand deserts, shell-strewn beaches, and mountains where farmers cultivate peaches and pomegranates on terraces hewn from rock.

And the people. While traveling between luxurious hotels where staff greet you with warm smiles each evening, it’s easy to feel that the nation you’re visiting is the epitome of hospitality. In Oman, however, this may truly be the case. Strangers on the street stop to invite you into their homes.

My journey in Oman began in Muscat, the historic coastal capital. Walid, my guide and driver for the week, welcomed me at the sleek new Muscat International Airport, designed to handle the increasing number of visitors. 'You won’t see anyone unhappy here,' he remarked as we cruised down a clear highway lined with pristine white houses. 'As soon as you set foot in this country, happiness follows you.' Initially, I suspected he must be a government spokesperson, given his enthusiastic proclamations. But after meeting more Omanis who spoke with the same exuberance about their homeland, I realized their pride was genuine.

Upon reaching the Al Bustan Palace, a Ritz-Carlton hotel, I was amazed to find it was an actual palace. The grand marble plaza led to an atrium topped with a magnificent dome, intricately adorned with swirling Arabic designs. The young man at the front desk mentioned that it was built by 'his majesty' just a few decades ago, originally for a summit of the Gulf Cooperation Council.

'His majesty' refers to Sultan Qaboos bin Said al Said, the reclusive absolutist monarch with a neatly trimmed white beard, whose portrait gazed down from the lobby wall, one of many displayed across Oman. Qaboos has ruled for nearly 50 years, and while his governance is autocratic, many Omanis attribute their country's tranquility and stability to his leadership. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have blockaded Qatar due to its alignment with Iran, which is backing rebel forces in Yemen while trading threats with Israel. Yet Oman manages to maintain friendly relations with all these nations, existing within its own peaceful enclave. Friendliness is a core trait of the Omani spirit.

The following morning, Walid guided me through the bustling city of 1.3 million. As we passed impressive houses featuring traditional Omani turrets, he noted that they were all constructed in the last 20 years. I inquired about what Muscat was like before this expansion. 'Smaller houses?' I asked. 'Desert,' he laughed. Just a few decades ago, Muscat was a small port town with a significant role in global trade. Strategically positioned near the entrance to the Persian Gulf, it has long served as a center for trade routes stretching from India to Zanzibar, off the African coast, blending diverse cultures. Walid shared that his ancestors hailed from Balochistan, in present-day Pakistan, which has deep-rooted connections to the sultanate. At the fish market by the port, he showed me bustling vendors bantering in Swahili as they haggled over 50-pound tunas displayed on shimmering tables.

Like many travelers to Oman, I made my way there with a layover in Dubai, curious if Muscat would mirror the hypermodern skyline of its neighbor. While both cities share some peculiarities, such as indoor sledding malls, their rapid growth driven by oil wealth, the contrasts are far more pronounced.

Firstly, Muscat has no skyscrapers, as they are banned by law. While Dubai’s architecture looks towards a shiny, chrome-and-glass future, Muscat’s structures, even the newest ones, reflect a rich history of crenellated sandstone. This longing for the past is epitomized by the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque, an expansive marvel of Indian stone and Persian carpets designed at the end of the 20th century, evoking the splendor of the ancient Islamic empires.

From left: The ornate dome of Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque in Muscat; visitors strolling through the mosque's courtyard.

Stefan Ruiz

From left: The ornate dome of Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque in Muscat; visitors strolling through the mosque's courtyard.

Stefan RuizAs I stepped through the entrance and neared the impressive complex, the dazzling white minaret and golden dome shimmered in the polished courtyard below. “What do you feel when you see this?” Walid asked after we removed our shoes and entered the grand prayer hall. It was a rhetorical question, which he answered with a simple, “Wow.” Walking through the expansive hall in my socks, I could only nod in agreement. The scale was immense, with a worshipper capacity of 20,000 and 1.7 billion knots woven into the carpet over four years. At the public information desk, staff treated us to halwa, a fragrant saffron pudding, served directly into our hands as they discussed the importance of religious tolerance. “We don’t endorse fanaticism,” said a kindly elder with a long white beard who joined me on the couch. “Oman has always been peaceful, and we wish for that peace to extend throughout the world.”

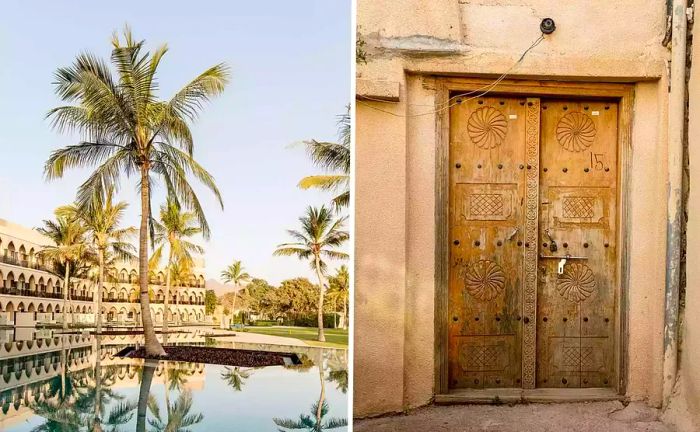

From the mosque, a brief drive along Sultan Qaboos Street leads to another of the classical-music-loving sultan’s ventures: the Royal Opera House. One of only four opera houses in the Middle East, it opened its doors in 2011 with a performance of 'Turandot,' conducted by the legendary Plácido Domingo. If you stop by during the day when performances are not taking place, you can take a tour for three rials (about eight dollars) and admire the array of musical instruments displayed in the lobby. Oman boasts a vibrant musical heritage, influenced by its role as a trading hub, yet the exhibit lacked any African-inspired Omani drums. Instead, I found myself captivated by artifacts from the royal courts of Europe, including lyres, flutes, and a charming pocket-sized violin known as a pochette. Not long ago, Western nations filled their museums with treasures acquired from places like Oman, and what better way to showcase Muscat’s rise and global aspirations than by inviting visitors to reflect on the relics of Western cultural history?

From left: The Royal Opera House in Muscat; an infinity pool at Anantara.

Stefan Ruiz

From left: The Royal Opera House in Muscat; an infinity pool at Anantara.

Stefan RuizOn my third day, Walid drove me along the coast to Sur, renowned for its traditional dhow-building — the wooden sailboats that historically transported slaves and spices across the Indian Ocean. We explored a factory where these vessels are still crafted, now repurposed as leisure boats for affluent visitors from the Gulf. Outside, a massive boat rested on wooden beams while South Asian workers sawed planks under the blazing afternoon sun. Afterwards, we dined at a simple restaurant where patrons lounged on carpets, enjoying a traditional Omani meal: a whole red snapper marinated in curry, grilled, and served over fragrant biryani studded with cardamom pods — a true taste of the Indian Ocean on a plate.

Later that day, after traversing the rugged Hajar mountain range that lines Oman’s northern coast, I climbed onto the back of a camel named Karisma (after the Indian actress Karisma Kapoor) and set off across a mesmerizing sea of dunes that perfectly matched every Westerner’s vision of an Arabian desert. I was on the outskirts of the Wahiba Sands, following my turbaned guide, Ali, toward my overnight stay at a desert camp about half an hour away. I knew that Bedouins don’t exclusively travel by camel anymore (Toyota trucks have become the preferred mode of transport), but the authentic vastness of the empty landscape and the sting of sand in my face heightened my eagerness to converse with Ali — to learn about Bedouin life, Toyotas included.

Stefan Ruiz

Stefan Ruiz'I am not Bedouin,' Ali stated after we dismounted from the camels. 'I come from Pakistan.'

As the evening unfolded, Ali and I chatted outside my opulent tent, set up by the camping company Canvas Club. It was spacious enough for a king-size bed and adorned with Oriental cushions, reminiscent of the luxurious accommodations a high-ranking British officer might have enjoyed during an Arabian campaign. He exuded a blend of cheerful formality and candidness, sharing stories of his village, the devastating drought that wiped out his family's livestock, and how it compelled him to leave home in search of work in Dubai, where he initially donned a Bedouin costume for tourists. 'There were floodlights, DJs, quad bikes, dune buggies, and all sorts of luxury cars,' he chuckled, 'in the middle of the desert.' He expressed a preference for the tranquility of Oman, where the desert was serene and the nights were adorned with stars.

A luxury camping company, Canvas Club, has set up a traditional Bedouin-style tent.

Stefan Ruiz

A luxury camping company, Canvas Club, has set up a traditional Bedouin-style tent.

Stefan RuizBefore dawn, I ventured out of my tent to conquer the dunes. The sand felt cool against my bare feet, and as the sky began to brighten, I spotted tiny, stitch-like tracks crisscrossing the sand—footprints of beetles, as Ali later explained. I climbed what I believed was the highest dune, only to discover an even taller one nearby, prompting me to ascend it as well, and then the next, until I lost sight of my tent. I settled in the sand, watching the sunrise transform the desert into a canvas of gold, rose, lavender, and red. Upon retracing my steps back to camp, I found Ali tending a fire made from the dry brush, preparing an omelette, which I paired with coffee brewed in a French press at a quaint table set up in the sand. My desert adventure didn’t impart much about Bedouin culture, but it did offer insight into another facet of Oman. With over 2 million residents like Ali—migrants from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and the Philippines—seeking to earn enough for their children's education or to fund necessities back home, their stories are vital to grasping contemporary life in Oman.

When you picture Arabia, the desert comes to mind. However, Oman is also home to magnificent, rust-hued mountains and mesas where farmers have cultivated apricots, walnuts, olives, roses, grapes, and pomegranates on narrow ledges for thousands of years. These terraces are nourished by a unique irrigation system known as falaj. Each day, designated officials called areefs unlock a gate in a stone cistern atop the mountain, allowing just the right amount of water to flow down through a series of narrow channels carved into the rock.

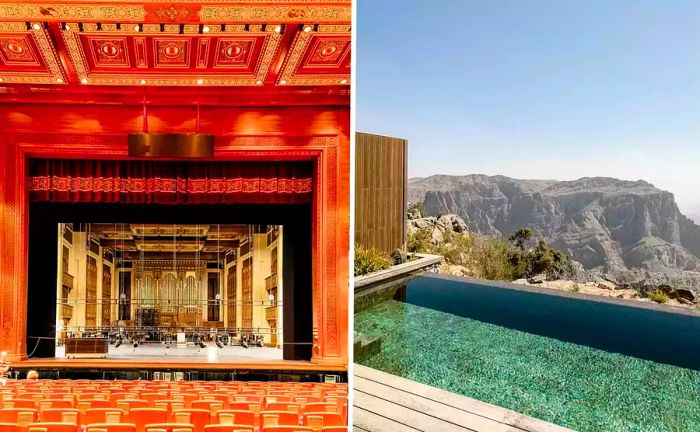

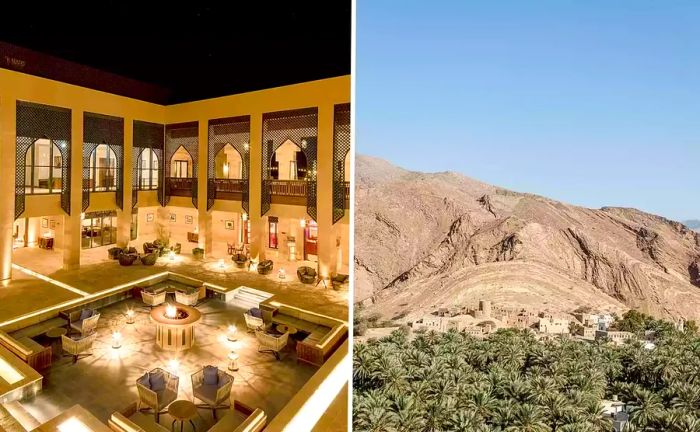

From left: A courtyard at Anantara; the remains of Birkat al Mawz, a settlement at the foot of Jabal Akhdar.

Stefan Ruiz

From left: A courtyard at Anantara; the remains of Birkat al Mawz, a settlement at the foot of Jabal Akhdar.

Stefan RuizDuring my stay at Anantara Al Jabal Al Akhdar, perched atop one of Oman’s highest peaks, I explored some of the stunning cliffside gardens. The upscale hotel chain operating here boasts locations in hidden gems worldwide, and like many leading hospitality brands today, it emphasizes harmony with the local environment and culture. On the “Green Mountain,” or Jabal Akhdar, the resort has landscaped its idyllic grounds with an abundance of native flora—figs, plums, lemons, and thyme—alongside winding streams inspired by the traditional falaj irrigation system. While the original structures that influenced these designs were built to sustain life in a challenging environment, the resort focuses on comfort and luxury. Beyond the lavish infinity pools and spa treatments, the genuinely warm and welcoming staff made me feel as though my charm was infectious.

One afternoon, a hotel guide accompanied me and a Belgian family to explore the villages nestled in the mountains. The weather was bright and pleasantly cool, typical of my days in the highlands—sunny enough for sunglasses yet cool enough for a sweater. The rugged stone houses were stacked upon one another, so standing at one entrance, I looked down at a neighbor's rooftop; the narrow streets barely accommodated a donkey cart and were primarily composed of steep stairs. I spotted a group of children playing soccer in one narrow alley and wondered how they managed to find a flat field for a proper game. Later, a local shared that when he and his friends were young, they would hike 45 minutes up the mountain carrying their soccer ball.

At one point during our walk, the guide noted that many of the terraced gardens appeared barren. She explained that roughly a decade ago, rainfall in the mountains had diminished, and a creeping drought claimed another three to four terraces each year. The sultan is reportedly constructing a pipeline to supply desalinated seawater to these villages, but its effectiveness for sustaining delicate crops like peaches and grapes remains uncertain. In the meantime, the hotel has to transport 50,000 gallons of water up the mountain daily for its guests.

This prompted me to reflect on Oman’s complex relationship with oil. While oil is vital to the nation's economy, it also contributes to increasing global temperatures and dryness, impacting Oman significantly—after all, it is among the hottest and driest places on earth. I posed a hypothetical question to the villager who spoke of playing soccer atop the mesa: if he could reverse climate change's effects and restore his family's orchards but had to forfeit the comforts of the oil economy—like roads, vehicles, air conditioning, hospitals, and universities—what would he choose? He opted for the comforts, admitting, “I am too used to this,” yet he recognized that Oman would need to move away from oil eventually, hoping the burgeoning tourism sector would fill the gap. He had pursued engineering to work in the oil fields, but with declining oil prices, he now found joy leading adventure courses at the hotel near his childhood home. “I like it,” he stated. “The world is coming to us.”

My journey in Oman concluded at the Musandam Peninsula, which juts northeast into the Strait of Hormuz, edging towards the Iranian coast and creating a crucial passage for ships traveling between the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf. Getting there proved to be an adventure in itself. Musandam is entirely isolated from the rest of Oman, reminiscent of Alaska's remoteness from the Lower 48 states. I had to fly from Muscat to Dubai, then take a two-hour taxi ride through sprawling urban areas before reaching the Musandam border. As soon as we crossed back into Oman, jagged mountains rose dramatically around us, and a tranquil silence enveloped the deserted road, making the noise and bustle of Dubai feel worlds away.

From left: The stunning beach at Six Senses Zighy Bay, a resort on the Musandam Peninsula with breathtaking views of the Gulf of Oman; dishes crafted with local ingredients, many of which are cultivated on-site.

Stefan Ruiz

From left: The stunning beach at Six Senses Zighy Bay, a resort on the Musandam Peninsula with breathtaking views of the Gulf of Oman; dishes crafted with local ingredients, many of which are cultivated on-site.

Stefan RuizI spent three enchanting days at Six Senses Zighy Bay, a luxurious resort set between the mountains of Musandam and the Gulf of Oman, located on a secluded crescent beach adorned with tropical shells. Just a short stroll along the shore led to Zaghi, a fishing village that had remained largely untouched by modernity until the resort's arrival 11 years ago, which introduced a road and electricity. The resort mirrored the village’s opulence, with villas constructed from palm thatch, stone, and mud. Meandering pathways of raked sand connected the buildings, pools, and the organic garden, where I wandered among buzzing bees and fluttering butterflies, plucking leaves of Indian basil, za’atar, and various herbs and vegetables.

As I held the herbs to my nose, I recalled how the chef had incorporated them into my seven-course dinner the previous night. That evening, I ascended over a hundred stone steps to an open-air restaurant perched on the mountainside, overlooking the bay. There, I indulged while gazing at the twinkling lights of container ships drifting at sea. I savored ravioli filled with silky quail confit, a lobster tail drizzled in an orange emulsion, and octopus that had been sous vide to perfection. While these dishes weren’t traditional Omani fare, the local ingredients showcased in a Western style reflected the country’s culinary heritage, influenced by diverse cultures—spice traders bearing curry from India and saffron from Persia, fishermen with fresh kingfish and tuna, and desert nomads who slow-cook goat and lamb in earth ovens.

On a hot, clear afternoon, I encountered a friendly and self-assured Bulgarian paraglider pilot. His confidence was reassuring as I was about to entrust my life to him. A driver navigated a winding mountain road, parking near a cliff that overlooked the sea. The pilot unfolded his paraglider and strapped us both into our harnesses, adjusting the ropes until the fabric billowed with the wind. We sprinted together toward the cliff’s edge and leaped into the air.

As I jumped, I felt the harness secure around me, and I settled into my seat while the pilot guided us higher and higher on the warm air currents, the wind whipping past. We glided over a rugged ridge, the jagged rocks jutting up like pikes on a castle fortress. The pilot swooped into a gap between the cliffs and executed a few thrilling loops before heading back toward the bay. Below, I could see the thatched roofs of the villas alongside the mud-domed mosque of the fishing village — a blend of the luxurious and the humble, old and new, coexisting harmoniously. The breathtaking landscape of Oman unfolded beneath my dangling feet. Gradually, we began our descent, spiraling down in leisurely loops until we were racing down the soft sandy beach toward the sea.

City, Desert, Mountains, Beach

Oman boasts a rich tapestry of landscapes—allocate yourself a week or more to experience its diverse offerings.

Getting There

The most convenient option is to connect through a nearby Gulf city such as Doha or Dubai, both only a 90-minute flight from Muscat. U.S. citizens should secure an e-visa ahead of time.

Muscat

The seaside Al Bustan Palace, a Ritz-Carlton Hotel has recently undergone renovations that highlight traditional Omani architecture. Other luxurious openings around the capital include the Kempinski Hotel Muscat and the Jumeirah Muscat Bay, both set to debut later this year.

Wahiba Sands

Located a few hours southeast of Muscat, this desert region is more accessible (and welcoming) than the renowned Empty Quarter, which spans a quarter of the Arabian Peninsula. Canvas Club offers a lavish, Bedouin-style camping experience under the stars.

Jabal Akhdar

A three-hour drive northwest from Wahiba takes you through scenic hillside villages and flourishing date plantations. The area’s newest addition is the impressive 115-room Anantara Al Jabal Al Akhdar, recognized as the highest resort in Arabia. Another superb choice is Alila Jabal Akhdar, the first luxury resort in this region, featured on our It List of top new hotels in 2015.

Musandam Peninsula

Roughly a five-hour drive northwest of Muscat, this exclave is bordered by the eastern United Arab Emirates. To simplify travel and avoid multiple land border crossings, fly into Dubai and then drive. The luxurious Six Senses Zighy Bay is definitely worth the extra effort.

Travel Guide

This journey was organized by Amalia Lazarov from Travelicious Travel, a proud member of the T+L A-List specializing in the Arabian Peninsula. She visits the area multiple times a year, is fluent in Arabic, and collaborates with local businesses like Zahara Tours, which provide experiences like dhow sailing and hiking in Oman’s renowned wadis.

This story was originally published in the July 2019 issue of Dinogo, titled The Edge of Arabia. The reporting for this piece received support from Al Bustan Palace, Anantara Al Jabal Al Akhdar, Canvas Club, Six Senses Zighy Bay, and Zahara Tours.

Evaluation :

5/5