Expedition to the Geographical Center of North America

North Dakota is a land abundant with honeybees, their white hives dotting the lush green fields in every direction. It's said that there are so many hives that one could traverse the width of the state without ever touching the ground.

It's fitting that honeybees flourish in the Peace Garden State. With over 90 percent of its land dedicated to agriculture and ranching, North Dakota offers vast open spaces rich with untouched grasslands, where bees flit about as the guardians of the land beneath. Although honeybees don’t stay year-round in North Dakota, they always find their way back. They instinctively navigate towards their center.

My father used to call it big sky country, where my great-great-grandparents settled after arriving from Norway in the late 1800s, lured by the promise of fertile land. I was born in North Dakota, just like my father and his parents. Although my family moved to Germany when I was three, like bees returning home, we find ourselves headed back to the vast skies of North Dakota. The geographical center of North America is calling us, one of them, at least.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock

A Note on Geographic Centers

Throughout the United States, the concept of “centers” has often been romanticized as locations of significant importance, where one can stand and feel a connection in every direction. However, the U.S. Geological Survey states that there is no definitive definition of a geographic center and no standardized method for calculating it. Any claim to a place being a “center” is simply an approximation.

Over the last century, several states have passionately asserted their claims as the true “centers.” In 1918, residents of Lebanon, Kansas, hired engineers to prove that their town was the center of the contiguous states. Castle Rock in Butte County, South Dakota, claims to be the center of the 49 continental United States; just to the west lies the alleged center of all 50 states. Yet, the title of the geographical center of North America, which includes the USA, Mexico, and Canada, remains a topic of debate.

In 1931, inquisitive researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey balanced a cardboard cutout of North America on a point to determine its center. This method led them to pinpoint the heart of North America at coordinates 48.10° N, 100.10° W. On a map, this places North America’s geographical center about 6 miles west of a town named Balta, North Dakota, which is situated 16 miles southwest of Rugby.

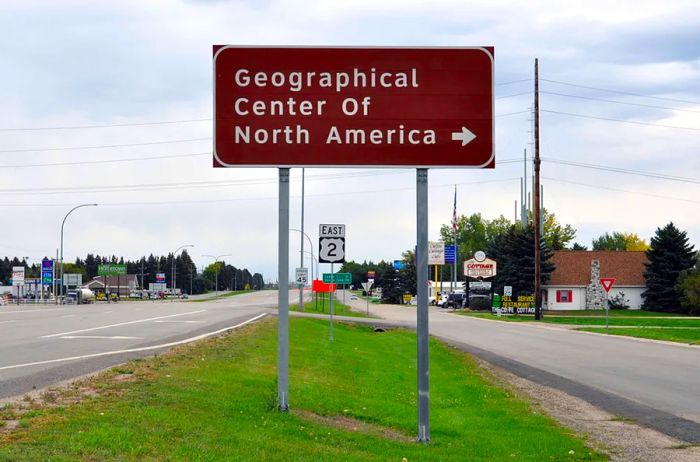

Rugby quickly embraced its newfound title: In August 1932, local Boy Scouts erected a 21-foot fieldstone monument at the junction of U.S. Highway 2 and North Dakota Highway 3, proudly declaring it the “Geographical Center of North America.” The town also revamped its seal to feature an outline of the continent with Rugby marked at its center. Since then, Rugby has fully embraced this identity: it hosts a “Miss Geographic Center” beauty pageant and celebrates “Geographical Center Day” every final weekend of September with street dancing, a basketball tournament, and even a mechanical bull.

This enthusiasm persists despite the U.S. Geological Survey's objections, which has never validated the claims of Lebanon, Castle Rock, Balta, or Rugby as geographic centers. In a 1964 report, they stated: “No government agency has officially established any points marking the geographic center of the U.S., the conterminous U.S. (48 states), or the North American continent.”

Nevertheless, Rugby deserves recognition for seizing the opportunity.

“Ya Oughta Go Ta, North Dakota”

Growing up far from its borders, I often heard tales of North Dakota: how it boasts more wildlife refuges than any other state, how Lewis and Clark lingered there longer than anywhere else on their expedition, and how Theodore Roosevelt remarked, “If it hadn’t been for the years spent in North Dakota and what I learned there, I would not have been president of the United States.” Family reunions were filled with relatives and that beloved rallying cry: Ya oughta go ta, North Dakota / See the cattle and the wheat, And the folks that can’t be beat / Ya oughta go ta, North Dakota / And you just can’t say goodbye.

Throughout all those years, I heard just two notable things about Rugby: my father was born there in the 1950s at a hospital called Heart of America, and that it was definitively the geographical center of North America. So, last fall, when the chance arose to explore Rugby, I told my father what my relatives often sang: we oughta.

Photos by Katherine LaGrave

On the Road

Our adventure to the geographical center of North America kicks off before dawn as I leave my apartment in New York and catch a flight to Fargo. At 30,000 feet above Minneapolis, my father departs from my parents’ home in northwest Minnesota. By the time I land, he’s already there, ready and waiting in the car.

For the first leg of our journey, we drive north on Interstate 29 towards Grand Forks, with my father behind the wheel and me in the passenger seat, watching glimmering fields and Russian olive trees whiz by. Years ago, my father worked on the construction of these roads, which seamlessly curve and straighten every five miles.

According to him, the road hasn’t changed much since those days when he labored under the sun. My dad isn’t one for reminiscing. What the landscape looked like when our ancestors first arrived is anyone’s guess. “It’s hard to imagine being here, wandering with six-foot-tall grass, completely lost,” he reflects.

Our first destination may not be the center, but it marks the beginning of my story: the town of Thompson, where my parents purchased 12 acres after meeting in the Peace Corps in St. Kitts during the 1980s, trading the heat for the cold, rain forests for plains, and an island for a landlocked state.

When I was born one January, my father was at work, so my mother drove cautiously to the hospital in Grand Forks. When I ask her what she recalls from that day, she simply says: it was bitterly cold, even for North Dakota, which shares temperatures similar to those in Orenburg, Russia, located in south-central Siberia.

This time in Thompson, the sky is as blue as the waters of St. Kitts, with prairie grasses swaying in greeting. We cruise slowly through the quiet town at 20 miles per hour, passing a gas station and the high school. We edge toward the old farm, and as my father speaks, he gently taps the brakes, crunching down the gravel road, with memories intertwining with our journey. A hawk swoops down from a telephone pole into the vast sky, but it feels like it’s just us and the wind. My father points. There’s where the pigs escaped. There are the neighbors who kept an eye on you and your sister. There’s where your mother and I would stroll through the woods and spotted a moose crossing the road. There’s where There’s where There’s where.

In stark contrast to the serenity of Thompson, Grand Forks, just 15 miles to the north, feels almost overwhelming. There are signs pointing to Winnipeg, as well as to Arby’s, Kohl’s, Ashley’s, Hobby Lobby, and C’Mon Inn. HELP WANTED. HIRING MANAGERS CREW. We settle into polished booths at the Italian Moon for lunch. Later, on my way to the restroom, I spot a photo on the wall of my father beaming from a sunlit moment in his youth, wearing #22 on his high school basketball team. Phil Jackson played basketball in North Dakota, too, he reminds me when I return and lean over a plate of chimichangas to share what I’ve seen. After finishing our meal, we drive two miles to the cemetery to honor my grandparents, our shoes sinking into the muddy ground. With no flowers to offer, we instead clear their graves with our bare hands.

As we exit Grand Forks, we see turbines spinning in the distance, their large blades harnessing the wind. Neat rows of trees provide a windbreak for the farms, protecting them from the very gusts that are captured and transformed into energy. We pass Devils Lake, the largest natural lake in the state, whose name is a loan translation of Dakota words mni (water) and wak’áŋ (“pure source,” or spirit).

We don’t really stop again until we arrive in Leeds, where we pause outside a powder-blue house and a man steps out, asking us, somewhat stiffly yet courteously, what brings us here. My father tells him that his grandmother used to live in this very home. “OK,” the man replies, turning his back to us. Isn’t it amusing how things that once belonged to us seem to linger on?

Photos by Shutterstock (L) and Katherine LaGrave (R)

A Great Debate

On a day in the 1970s, so forgettable that he can’t even remember when, David Doyle found himself at his desk in the office of the National Geodetic Survey. This government agency was tasked with determining the nation’s latitude, longitude, elevation, and shoreline—its motto: “Positioning America for the Future.” Suddenly, someone dropped a manila folder on his desk, bulging at the seams. It bore just one word: Centers.

At first, Doyle suspected it was a joke. Perhaps a punishment of sorts. Inside the folder, he found no scientific data or geodetic analysis; instead, it contained hundreds of letters from the public regarding geographical centers, some dating back to 1945. Why am I stuck with this thing? he recalls thinking. But as more letters arrived, his outlook shifted. “I began to realize that people are genuinely passionate about this topic,” he says.

Nowhere is the debate over centers taken more seriously than in North Dakota. In a state that ranks as the second least-visited by American tourists (after Alaska), holding any claim—no matter how peculiar—holds weight. It signifies visitors. Revenue. An attraction to build dreams upon. Thus, it’s not surprising that Rugby’s proclamation as the Geographic Center of North America has stirred controversy. After all, thus says the Lord: Let not the wise man boast in his wisdom, let not the mighty man boast in his might, let not the rich man boast in his riches. Let not the center of it all boast about its center.

In 2015, whispers began to circulate across the plains when the co-owners of Hanson’s Bar in Robinson, North Dakota, consulted a map and concluded that the geographical center of North America was actually nearer to Robinson than Rugby—specifically, just a few feet outside of Hanson’s Bar. They even created a decal to mark the location and held a dedication ceremony to place it on the floor of their establishment, which proudly claims to be the oldest bar in North Dakota.

“We’re not geological scientists or anything,” says Bill Bender, the owner of Hanson’s, discussing their method for determining the geographical center. “It was basic, to be honest. But what we did was far more scientific than just cutting out a piece of cardboard and balancing it on a point. That’s not science; even a child could manage that.”

By 2016, Bender had gone beyond mere words: After realizing that Rugby hadn’t renewed its trademark on the term “Geographical Center of North America” with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, he paid $350 to acquire the rights. Almost immediately, he received a letter from Rugby’s town attorney, urging him to reconsider the claim. He politely declined.

Throughout the region, this move was seen as David overcoming Goliath. “North Dakota Bar Owner Pulls Off a Monumental Coup” shouted one headline. Another reporter wrote: “In this narrative, Rugby is akin to a municipal Phaethon, soaring on the geographical sun chariot lent by the USGS’s Helios until—intoxicated by its own sense of centrality and careless at the wheel—it veered wildly off course, ultimately struck down by the patent-snatching Zeus, Bill Bender.”

In early 2017, another Zeus appeared, this time in the form of a geography professor from the University of Buffalo, who suggested instead that the continental center was actually 145 miles southwest of Rugby, in a town named Center, which has a population of 588. Center, so named centuries ago because it was believed to be at the heart of Oliver County, viewed this designation as a significant honor—even if it took a while for someone to take the academic seriously.

“When they reached out to the city, the city official kind of dismissed them,” recalls Dave Berger, a lifelong resident of Center and member of the Community Club. “But then they contacted the county agent’s office, and he was the one who got in touch with me. From there, it just started to gain momentum.”

By early 2018, Center had also erected a monument to assert its claim: a massive 30,000-pound rock perched on a bluff 4.4 miles north of the town, offering views of the surrounding wind turbines. However, unlike Robinson, Center was more willing to seek common ground.

“We didn’t want to create—how should I put this—competition,” explains Berger, who led the effort to install the marker. “We aimed to avoid any hard feelings. Our intention wasn’t to take the title away from Rugby. So, we decided to call ourselves the ‘Scientific Center of North America,’ and that’s what we went with.”

After a lengthy legal battle, Rugby regained its trademark rights in April 2018. But the struggle on the plains is far from finished. Center is adding flagpoles, signposts, and seating around its monument. Meanwhile, Robinson, which continues to host an annual “Center Fest” complete with fire-eaters and a surströmming (fermented fish)-eating contest, established an International Center for Determining Centers in 2018, which Bender says will create a standardized method for identifying geographical centers.

“In terms of the terminology, Rugby can claim it, and they can use it,” states Bender, who served as mayor of Robinson from 2014 to 2020, a town with a population of 39. “But we’re going to have this discussion whether Rugby likes it or not.”

“When science has spoken, let the chatterers hold their peace,” penned Jules Verne in his 1864 work Journey to the Center of the Earth. Yet in this quest for the center, the science remains unclear, and official government agencies have remained silent. The chatterers know no rest.

The Heart of North America

When we arrive in Rugby at 7:15 p.m., the town is in slumber: doors are shut, signs displayed, and lights extinguished. By 8 p.m., we find ourselves at our hotel bar, munching on onion rings and enjoying a glass of merlot and a Blue Moon.

Established in 1886 at a pivotal junction of the Great Northern Railway, Rugby was named after the railway junction in Rugby, Warwickshire, England, in hopes of attracting English settlers. It met with moderate success: by 1920, the population stood at 1,424. A century later, that number has grown to 2,549, making Rugby the 20th largest city in North Dakota.

The following morning, we explore the Prairie Village Museum, which boasts eight exhibition halls, 22 fully furnished historic buildings, and over 50,000 artifacts from north-central North Dakota. My father discovers a carriage once used by his childhood doctor to navigate snowy fields in winter, while I marvel at the display of the “Scandinavian Giant,” Clifford Thompson—my 5’11 next to his towering 8’. The museum also features a gift shop where we browse T-shirts, magnets, mugs, and postcards, all under the watchful eye of the shopkeeper. Each item proclaims: Life Is Better at the Center. My father buys me two bumper stickers, silently acknowledging our contribution to promoting this center’s claim.

Right, this center. Finally, we head to the monument, relocated in 1971 after Highway 2 was widened to four lanes. It now shares a parking lot with True North Fitness and a Mexican eatery called Rancho Grande. Across the street, you’ll find a Subway and a Family Dollar. Flags from Mexico, America, and Canada flap in the breeze.

My father and I find ourselves at the heart of North America, gazing at the towering 21-foot obelisk before us. We make a polite circuit around its base, like diligent explorers inspecting this stone monument from all sides. We snap a selfie together. I climb the four steps to take a seat on a bench beneath the monument and pose for another picture. The signs inform us that we are 2,090 miles from Acapulco and 1,450 miles from the Arctic Circle. Meanwhile, we also find ourselves in the path of drivers in their trucks, searching for parking at Rancho Grande.

After spending what seems like just the right amount of time at the monument on this overcast North Dakota day, we head to Rugby’s Main Street for a meal. When the waitress looks down and asks if we’re locals, we point at each other: She’s tracing her roots. He was born here.

“Oh,” she responds, her curiosity piqued. “Which family do you belong to?”

Photo by Katherine LaGrave

Throwing Darts

You might be curious: What would it take to pinpoint the exact geographical center of North America with precision? Why can’t this be resolved once and for all, awarding the title to a single town? For starters, it would require substantial time, funds, and manpower—resources that the organizations responsible for making this designation—the U.S. National Geodetic Survey and the U.S. Geological Survey—are not inclined to invest, according to them. Furthermore, the conclusion likely wouldn’t vary significantly; the Geographical Center of North America would still be located in north-central North Dakota.

“It’s similar to throwing darts,” remarks Doyle, who retired from the National Geodetic Survey in 2012 after four decades. “If you hit the bull’s-eye, it doesn’t really matter whether you land precisely in the center or just inside the outer circle. Any point is equally valid.”

Rugby isn’t our final destination in North Dakota. In the days ahead, my father and I plan to travel to Esmond, Bismarck, Steele, and Jamestown, stopping to witness the world’s largest sandhill crane and the biggest buffalo. We’ll visit more cemeteries, enjoy more beers, and be asked once again if we are from “around here.” We’ll encounter real bison grazing alongside the interstate and pull over to observe them. Most significantly, we’ll walk on the land belonging to my great-great grandparents. And four days after departing from New York City and northwest Minnesota, amidst the wind and wheat, we will realize we are home. It appears that centers can indeed be wherever you discover them.

This article was initially published in 2020 and updated in March 2024 with new insights. It’s part of our Meet Me in the Middle series, celebrating the unique towns, cities, and outdoor spaces that await travelers between America’s well-trodden coasts. Explore more from Nebraska, Oklahoma, Utah, Wisconsin, and the Midwest.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5