Experiencing a Cruise Through One of Australia's Most Isolated Regions — Featuring Deadly Crocodiles and Timeless Landscapes

Photo: Matt Dutile

Photo: Matt DutilePinch me: I’m gliding through a prehistoric wonderland of towering sandstone cliffs in vibrant shades of orange and burgundy, an azure ocean, and inviting white-sand beaches that feel almost surreal. Such a breathtaking landscape would usually be bustling with tourists and luxury resorts, yet we cruise for miles in Zodiacs without encountering a single soul or animal. Life here is mostly hidden — lurking below the surface, concealed in the trees, or blending into ancient rocks. Some of it poses a danger, even a threat to life.

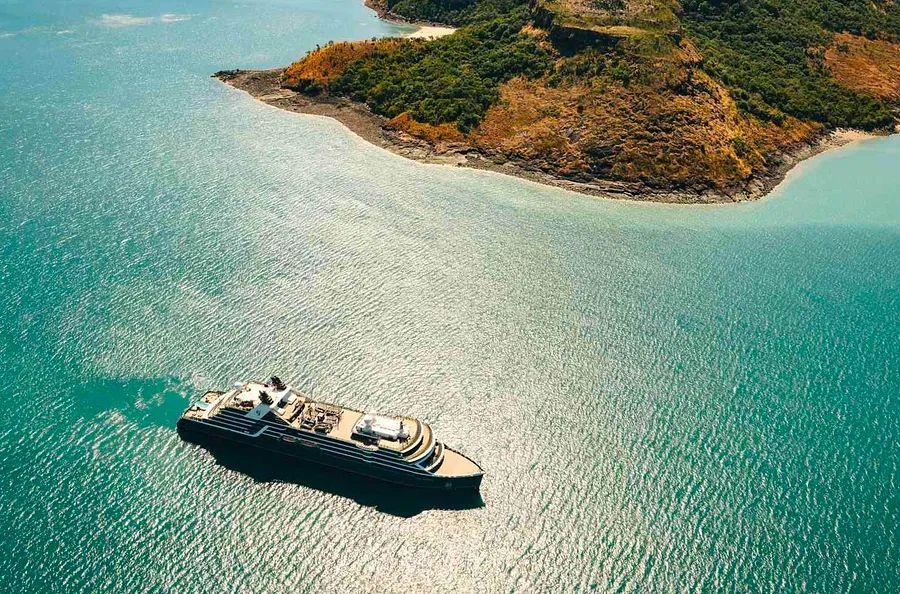

Welcome to the Kimberley in northwestern Australia, a region roughly the size of Sweden and so remote that even many Australians never set foot here. It’s among the world’s last great wildernesses, with a sparse population, nearly half of whom are Aboriginal. Here I find myself, a self-proclaimed wuss with a tendency toward catastrophic thoughts, embarking on an expedition with the 264-passenger Seabourn Pursuit during its inaugural sailing in June 2024. With the Kimberley now a hot spot for expeditions, I had to join this 10-day journey from Broome to Darwin, despite my initial hesitations.

During our first excursion, while idling in a Zodiac close to the mothership, we received a briefing on the fierce saltwater crocodiles that might be lurking beneath and around our rubber boats. Greg Fitzgerald, one of 24 expedition team members and our guide for the day, seemed almost gleeful as he rattled off a flurry of croc facts: Salties are stealth hunters, creating no wake or bubbles in the water. You won’t see them approach. They can detect a Zodiac from a kilometer away. They swim swiftly and can even sprint on land, just in case you’re considering stepping ashore. They eat humans. They even consume one another.

“Saltwater crocodiles are the oldest reptiles on the planet, the ultimate predators. They can grow up to 19 feet long and weigh over 1,000 pounds,” he explained in a thick Aussie accent. "Never put your hands or legs in the water. Do not stand up unless I give the go-ahead," Fitzgerald warned, as if I were contemplating it.

Photo: Matt Dutile

Photo: Matt Dutile“Can a crocodile leap onto a Zodiac or bump it from below?” I asked, my voice shaking. “I won’t say it’s impossible, but I’ve never encountered it,” Fitzgerald shrugged. With those reassuring words, we sped off, all leaning slightly forward in our Zodiac as instructed, and I was probably the most inclined. Although we wore life jackets, I’d prefer to fall into the boat rather than into the water.

Though we don’t spot any crocodiles today, the wealth of knowledge we gain about this ancient region is overwhelming. For instance, Fitzgerald highlights the underwater mangrove forests that line our ocean route, pointing out the yellow leaves drifting in the water. “These are sacrificial leaves,” he explains solemnly. “To survive in saltwater, the mangroves must sacrifice these leaves, which secrete salt to keep the trees thriving.”

Photo: Matt Dutile

Photo: Matt DutileThe sandstone cliffs flanking our waterways are an astonishing 350 million years old, crowned by flat plateaus adorned with acacia trees. Their layered, compressed, and rugged formations, shaped by sun, water, and time, resemble faces and sandwiches — one even earns the nickname ‘lasagna.’ I can’t resist taking countless pictures, as no two perspectives are the same.

Even though it's winter, the heat here is intense, marking the only season when expedition ships can visit, as the rainy summer brings typhoons and unbearable warmth. The temperature feels hotter than the reported high 80s, with the sun blazing through my protective hat and clothing. “Drink a liter of water every hour,” Fitzgerald advises. He’s spot on. If we don’t, dehydration and fatigue will take their toll. The Seabourn Pursuit falls silent when cruisers aren’t out exploring — naps are definitely the order of the day.

Photo: Matt Dutile

Photo: Matt DutileDespite the heat, I find myself utterly captivated. Each day unfolds like a spectacle. Picture this: cruising on an ultra-luxury expedition ship, where every suite is a lavish retreat with marble baths, and caviar and drinks flow without charge. Yet, the moment we board a Zodiac, we are whisked back to ancient times, surrounded by fossilized dinosaur footprints and unseen dangers lurking beneath. I can’t help but half-expect a T. Rex to emerge from one of those cliffside plateaus, like a next-gen Godzilla or a chest-thumping King Kong. It feels like a film set poised for a dinosaur-led adventure.

As someone who tends to worry, I find our expedition team — mostly composed of laid-back Aussies eager for adventure and committed to our safety during every excursion — to be absolute champions. They scout for crocodiles before and during our shore landings and snorkeling trips, ensuring we all make it back to the boat safely, and I’m particularly impressed by how they assist the older guests.

Our expedition team is positively exuberant, as if the presence of crocodiles, venomous spiders, and poisonous snakes only heightens the excitement. Fitzgerald shares that there's a rare snake with a single fang whose bite can be lethal within 30 minutes. I admire team member Sue Crafer, a world-class yacht racer. Before we head to the Horizontal Falls, Crafer advises, “Absorb your surroundings. Feel the place.” She encourages us to inhale the iron scent from the sandstone, her face glowing with joy as she breathes deeply.

We arrive at the Horizontal Falls in Talbot Bay — the only ones of their kind in the world — where extreme tidal forces push water through narrow gorges, creating the illusion of waterfalls flowing horizontally. Crafer explains that the water can reach speeds of up to 10 knots, matching our ship’s pace, as she maneuvers our Zodiac to the edge of the Falls. We skid and swirl, reminiscent of the Mad Tea Party ride at Disney World. Suddenly, Crafer receives a radio call and somberly informs us of an incident involving another Zodiac. She expresses her hope that no one is injured. Our group’s wonder shifts to anxiety until we reach the affected boat and find a cheerful Seabourn crew welcoming us with glasses of Champagne and passionfruit popsicles.

Photo: Matt Dutile

Photo: Matt DutileNext, we head to Paspaley, a pearl farm in Kuri Bay, which is a unique stop — Seabourn is one of only two cruise lines allowed to visit. We get a quick lesson on how South Sea pearls develop over a two-year period and even sample oyster pearl meat — which tastes delicious, akin to scallops — brought back by our chef for a sunset caviar celebration.

One unforgettable morning, we wake at 5:30 a.m. for a Zodiac adventure to Montgomery Reef, estimated to be around 1.8 billion years old. The sunrise sets the dark sky ablaze with vibrant orange hues, making the early wake-up exhilarating. We speed past green sea turtles, their heads briefly surfacing before disappearing. This coral reef, the largest inshore reef in the world, ebbs and flows with the Kimberley’s extreme tidal changes, which can reach an astonishing 30 feet in a single day. At low tide, the reef seems to rise from the ocean, revealing lagoons, inlets, waterfalls, and mangroves, while at high tide, it vanishes beneath the waves once more.

We marvel at ancient cave art in two locations; these artworks are thousands of years old — some may date back as far as 65,000 years, although no one can say for certain. At Freshwater Cove, members of the indigenous Worrorra tribe invite us to partake in a cleansing smoke ceremony and paint our faces with ochre. This experience feels both joyful and surreal, and I can’t help but smile widely. Before we admire the sacred art, a Worrorra guide offers a prayer in his native language. We are captivated by the delicate drawings — a cyclone shaped like a spider web, a hand, a turtle, and a fish — leaving us with more questions than answers, pondering who created them and what their lives were like so long ago.

Photo: Matt Dutile

Photo: Matt DutileAt last, we spot crocodiles on the sandy banks of the Hunter River. We cut the engine and drift closer. One is estimated to weigh around 1,200 pounds, likely male. I lock eyes with him, so reptilian and ancient, and I’m filled with goosebumps.

As our cruise nears its conclusion, it’s the inaugural day for Seabourn Pursuit, and all passengers gather for a shoreside ceremony on Ngula (Jar Island). Seabourn has spent years fostering relationships with the Wunambal Gaambera Traditional Owners to reach this moment. (Traditional Owners refers to Indigenous peoples who hold a traditional connection to their land, from which their ancestors were forcibly removed.) These Traditional Owners, flown in by helicopter, serve as the godparents for Seabourn Pursuit, marking the first time Kimberley’s Indigenous people have taken on this role for any expedition ship, even though vessels have been navigating these waters for decades.

Photo: Matt Dutile

Photo: Matt DutileSeabourn also supports tourism initiatives that enable Traditional Owners to return to their land during the dry season and sell their exquisite arts and crafts to all expedition ships, not just Seabourn’s. Their faces radiate pride and joy, and tears glisten in our eyes. Instead of the customary Champagne bottle for christening the ship, we have a special one made of sugar and filled with Kimberley sand — a meaningful gesture towards sustainable tourism that I wholeheartedly embrace.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5