How Tierra Bomba, Cartagena’s “Hidden Gem,” Sparked a Recycling Initiative

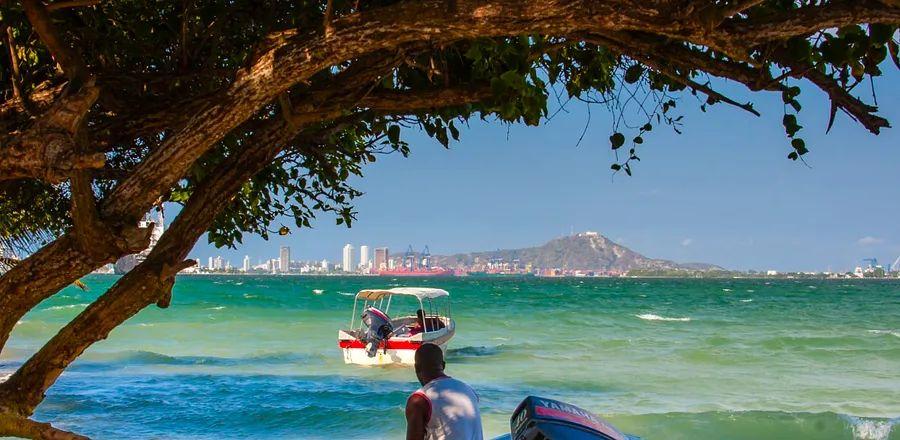

From the lively Walled City of Cartagena, visitors can gaze across the water to see the seven-square-mile island of Tierra Bomba. With a population of around 9,000, it's surrounded by rugged black coral cliffs and sandy beaches, adorned with vibrant churches, palm trees, and kapok trees, alive with children riding motorbikes. Once a crucial defense against pirates and armies, locals remember a time when tourists flocked here for shopping, sunbathing, and historical exploration—featuring a 17th-century castle, an 18th-century fort, and a sprawling network of tunnels built by Spanish colonists using enormous coral blocks.

In 2015, independent hotelier Portia Hart considered Tierra Bomba for her beach club venture. It was the quickest escape from the city, set in a stunning location with limited job opportunities, allowing new enterprises to make a positive impact on the local community. At that time, there were only a few modest beach clubs offering basic amenities. While foreign tourism surged by 500 percent on the mainland and other islands like the Rosario Archipelago thrived, Tierra Bomba saw a decline in international visitors to its once-thriving attractions over the last 15 years. Colombians referred to it as the “forgotten island.”

“When I first visited, my immediate thought was, ‘Why is it so empty here?’” Hart reflects.

The reason, she would discover, is intricate and tied to Indigenous rights and the legacy of formerly enslaved African and Caribbean communities that settled Tierra Bomba. Unlike any other island in Cartagena, there is no land ownership here. Residents and business owners may occupy a location legally, but they cannot claim ownership of it.

This situation has sparked years of turmoil and legal battles, deterring potential investors. As they witnessed land disputes persist, developers who were once hopeful about the island’s economic prospects redirected their funds elsewhere, as did the government. Essential modern infrastructure—like sewage systems, paved roads, and running water—remains absent. Drinking water arrives by barge, costing 240 times more than on the mainland, and the nearest medical facility can only be reached by boat.

Photo by Alexandra Marvar

For Hart, a 39-year-old British-Trinidadian who had recently relocated from France to Cartagena, the infrastructure challenges on Tierra Bomba appeared manageable. In fact, they presented an opportunity with little competition and a community eager for economic growth. In July 2016, she launched Blue Apple Beach, a vibrant beachfront retreat featuring five rooms and six cabanas, just a short motorbike ride from Bocachica, the island’s largest town.

However, she soon discovered that the most significant issue wasn’t the erratic electricity, lack of running water, or the dilapidated dock that vanishes under rough seas. The island lacked a trash disposal system. Waste was simply sent to above-ground dumping sites in the woods, much of which eventually ended up on the shores.

“I think I may have underestimated the logistical challenges—like many young people starting their first business,” Hart reflects. However, finding a solution turned into a series of humorous mishaps. After learning that the hotel waste was being dumped on the island, she started loading it onto boats to take back to the mainland, which she described as “extremely costly and complicated.” Consequently, Blue Apple Beach sought to minimize waste in every way possible, hiring waste management expert Caitlin Oliver, who visited the mainland center where their recycling was sent.

What the team discovered about glass was shocking: Employees informed Oliver that they kept accumulating glass until the storage room was full—and then sent it to a landfill anyway, as there was no market for it. “That’s when we realized that in Cartagena, no one recycles glass,” Hart explains. Not even businesses that believed they were recycling.

While glass is infinitely recyclable, it can be challenging to process affordably. The United States hasn’t cracked this yet, and neither has Colombia. A recent coastal cleanup initiative reported that a group of volunteers collected over 100 pounds of glass from the beach and nearby communities in just one day on Tierra Bomba—and they had only covered 3 miles of the roughly 27-mile coastline.

After a lengthy year of trial and error, the Blue Apple team successfully figured out how to manage all other types of waste in environmentally friendly ways. However, glass remained a challenge they needed to address directly. They acquired the Colombian coast’s first glass pulverizer and began upcycling glass bottles into products that locals could sell for income.

Before long, Hart recalls, other clubs—even her competitors—began to reach out: Can you assist us in recycling our glass? By spring 2018, she had devised a solution—the glass recycling and upcycling nonprofit known as the Green Apple Foundation.

People seek to create change not just for their own sake, but for the future of their children.

Five years later, it’s a warm February morning in Cartagena. Caracaras glide above the Spanish colonial rooftops, while parakeets flutter from the power lines that stretch over the roads near the ancient city wall. Early risers navigate the streets beneath the clock tower’s shadow, and a bicycle, pulling a green-and-white cart, rattles over the cobblestones of the plaza, creating a melodic clinking of glass.

The cyclist is traversing the Walled City and Getsemaní districts, collecting empty bottles from the bars and restaurants that served the night before. Soon, back at the docks, he and his small team will load heavy plastic mesh bags filled with dozens of pounds of glass onto a boat, ready to set sail across the bay.

At their destination on Tierra Bomba, sunlight streams into a cozy glassworks studio. Albert Valiente, Green Apple’s operations manager, rests against the windowsill. His glass processing area lies out of sight behind the main building of the resort, but this front room serves as his connection to the public. Here, a central table displays an array of glassware—blue, brown, clear, and green—available for purchase.

Green Apple has experienced rapid growth: Currently, 27 hotels and restaurants are involved, contributing six to eight tons of discarded glass each month. Collectively, they are diverting hundreds of tons of glass away from Cartagena’s landfills. Valiente’s team processes about 85% of the collected bottles into fine sand, which is then sold for use in concrete for building projects like this one. The remaining 15%, the thicker bottles, are transformed by a group of six women in the workshop into housewares: rocks glasses, tumblers, carafes, and light fixtures.

A native of Bocachica, Valiente observes a growing interest in recycling among the island's residents. "People want to create change not just for themselves, but for their children's future," he explains. Fishermen on Tierra Bomba are noticing fewer fish in their nets. Valiente points out that weather patterns are shifting and coastal erosion is encroaching on the land. One report indicates that nearly 60 homes have collapsed into the sea within just two years. Locals attribute this to shipping traffic, rising sea levels, and pollution. "The environment is changing every day here," he remarks. "As small as our [recycling] efforts may seem, we strive to make a difference."

Yohiceth Gómez, Valiente's wife, is one of six artisans working at the Green Apple workshop. "We are driven by the environmental impact we can create through recycling," Gómez shares while standing alongside her coworker Greisis de Avila in the glass workshop. While she appreciates the income they earn, she emphasizes that their primary goal is to benefit the planet. "We’re not just reducing landfill waste; we’re also giving it a second life."

Over the past year, the artisans have successfully sold over 2,700 products to more than 150 businesses and customers. (They share the profits with the foundation at a 70/30 split.) Diners at popular Cartagena restaurants and bars like Caffe Lunático, Celele, Carmen, and El Baron enjoy drinks from Tierra Bomba’s upcycled glasses.

De Avila, one of three single mothers working at the workshop multiple days a week, reflects: "Look at all we have accomplished so far."

Photo by Alexandra Marvar

Wheelbarrows transporting today's glass delivery rumble along a sandy path from the dock. Hart sits barefoot at a table in the sand, surrounded by the artwork of artist-in-residence Diana Herrera, featuring portraits of Bocachica locals. She's enjoying a great day.

"I just had one of the most renowned restaurant owners in the country approach me, saying, 'I want to launch Green Apple in Medellín this year,'" she shares. "What’s been truly exciting is hearing business owners express their desire to establish their own versions of it on their properties, wanting to lead similar initiatives in their cities. From the very beginning, we aimed to create something that could be easily replicated."

Once overlooked, the island’s hospitality industry is now thriving. Thanks to a surge in post-pandemic tourism, new clubs are opening one after another. Over 20 now line the coastline, particularly on the northern edge of the island, where day-trippers can enjoy views of the Cartagena skyline from beach cabanas and swim-up bars. Three years ago, the government launched a trash barge to transport waste to the mainland, reducing the need for ground dumping sites.

Hart and Valiente recognize that as the island builds its tourism industry from the ground up, they are setting a precedent for others to follow. Green Apple has already advised on establishing independent glass recycling facilities at three other resorts on Tierra Bomba. Valiente mentions that other locations have ventured out on their own to create similar initiatives, which fills him with pride. "It proves we are pioneers," he states.

Evaluation :

5/5