In Uzbekistan, a Writer Discovers Blinis, Family Heritage, and the Home of Her Father's Birth

The manager of the Samarkand guesthouse claims the breakfast room is a place where wishes come true. I think about sharing the story of my journey from Los Angeles, but I remain skeptical of his beliefs. Instead, I immerse myself in the feast—blinis, cherry compote, fried eggplant. The walls display a vibrant array of intricate carvings and paintings from the Jewish family that once resided here. Above the remnants of an altar hangs a blessing in Hebrew: May you be blessed when entering and blessed when leaving.

Such a blessing feels necessary as I find myself in Muslim Central Asia, driven by a challenging mission: to trace the footsteps of my Jewish family more than 75 years after they departed and never returned. Unlike the Bukharan Jews, who had deep roots in this ancient city, my Polish Jewish family had a much shorter, more fragile connection to Uzbekistan. They were part of the many Jews who sought refuge in Uzbekistan during the Holocaust.

At the onset of World War II, my grandparents fled east into Soviet-held territory. In June 1940, they were deported to Siberia, enduring a year of forced labor in camps. Upon their liberation, they traveled by train to Uzbekistan in the fall of 1941, searching for safety. Samarkand was overwhelmed with refugees and unable to accommodate more. The authorities directed them to the village of Juma, 18 miles away, where they lived for four years, struggling to make a living on the black market. My father was born in that dusty village.

Seventy-six years later, as I wander the alleyways of Samarkand, I sense my father's presence among the stunning azure-tiled mosques and mausoleums. Here, at the crossroads of the Middle East, Russia, and China, I envision him pausing in awe at these structures—both familiar and foreign—a part of his heritage yet completely new. But he is not by my side.

I sit alone in the breakfast room when a woman dressed in black enters confidently. Anait, an Armenian Uzbek, introduces herself as my guide on this quest to uncover my father's roots. I share with her that he had always intended to return to his birthplace, but after his mind faltered two years ago, his body followed suit. Uzbekistan was merely a name on his passport, in his obituaries, and on his death certificate—a place shrouded in mystery. Tears begin to fall.

“You’re here with a purpose,” Anait says. “You are realizing his dream.” She then suggests it’s time to begin our work.

I made my way to Uzbekistan alone, but friends later joined me in Samarkand. I introduce Anait to Oleg and Lilia, scholars who escaped Russia at the onset of the Ukraine war, now deemed enemies of the state by Vladimir Putin. Like my grandparents before them, they view Uzbekistan as a temporary stop, not a final destination.

The four of us squeeze into a white micro taxi bound for Juma. I gaze out the backseat window, feeling cramped and hot as sweat runs down my legs. I try to envision what my grandparents experienced on their journey to an unfamiliar home in a foreign land. Like our group today, they may have also passed cotton fields, donkeys pulling carts, and vendors selling towering piles of watermelons.

Deep within the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum archives, I discovered an address my grandfather had listed as the family's home in Uzbekistan: Kaganovitcha 5, Juma. However, every Uzbek I consulted insisted that street name had likely changed. It was originally named after Lazar Kaganovich—known as Iron Lazar—one of Stalin’s enforcers, notorious for his involvement in the devastating famine that claimed millions of lives.

Upon our arrival in Juma, Anait and Lilia hail taxi drivers, inquiring if anyone knows Kaganovitcha Street. Each driver shakes their head. We then step into a nearby restaurant and ask the patrons inside. The answer remains the same: no.

Suddenly, I remember that my grandparents had come by train, spending their first night on the ground next to the station before finding a nearby house. The woman at the restaurant informs us that the old depot lies just across a bridge. Anait recalls a detail I had shared: My grandparents rented from a Tatar family, part of an ethnic Muslim minority. Under Soviet rule, neighborhoods in Samarkand were segregated, and Anait assumes Juma followed suit. She queries the manager about a Tatar settlement in Juma. Bingo. But that was long ago. Only one Tatar group remains now.

The conversation moves too quickly for my companions to keep up. It isn’t until we cross the bridge that I realize the middle-aged man from the restaurant, with kind eyes and a relaxed demeanor, has offered to drive us to the Tatars. He opens the doors of a Soviet Lada sedan, its windows broken. “This used to be the coolest car around,” Anait reflects. The driver navigates us through cobblestoned streets, honking and waving at every vehicle that passes.

In a courtyard on the town's edge, we encounter the four remaining members of Juma’s Tatar community, taking a break from their morning tasks. They are farmers with roots tracing back to Crimea. A woman adorned in a vibrant floral headscarf and cutoff jeans recounts how Stalin deported her mother to the Ural region, before her mother eventually made her way to Uzbekistan seeking arable land. Another member explains his family’s arrival was not voluntary: After the German retreat from Crimea in 1944, the Soviets forcibly loaded over 183,000 Crimean Tatars into cattle cars; over weeks, the entire community was relocated to Central Asia. My thoughts swirl as I try to grasp the intricate layers of the more than a million people the Uzbeks welcomed during and after World War II.

Most of this ethnic diversity has now vanished. The woman confirms that they are the last of the Tatars and that they too have never heard of Kaganovitcha Street. Just then, a lively discussion begins: they mention a Russian woman whom they refer to as the oldest person in town. Perhaps she might have some knowledge.

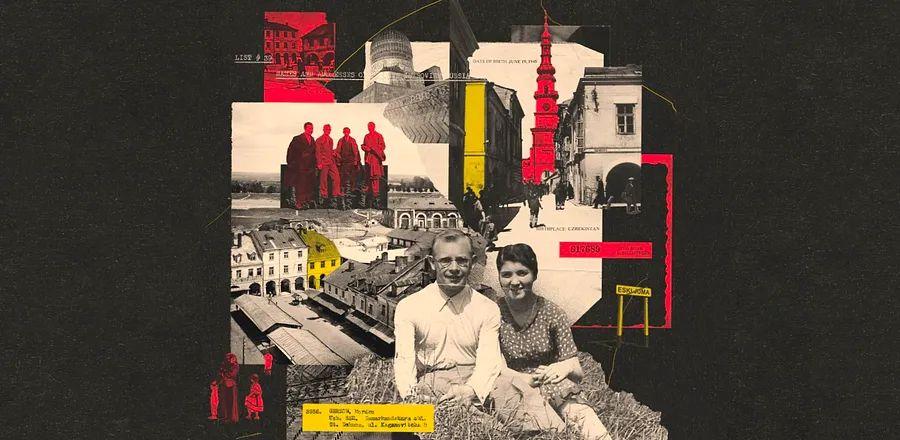

Illustration by Israel Vargas

Through the gate of a vibrant turquoise house, we spot a lively woman with black and purple-dyed hair, dressed in a velour jacket. She warmly invites us inside. The walls are painted the same vivid turquoise, carpets adorn the floor, and freshly picked raspberries from her garden sit on the counter.

The woman, named Zoja, serves us black tea and converses comfortably with Anait and Lilia in Russian. Suddenly, they exclaim in unison, “Wow, wow!” We no longer need to search. We have discovered the one person who seems to remember Kaganovitcha Street. Miraculously, we are standing on it. Zoja has spent most of her life at what was once #6 Kaganovitcha. The address I’m looking for, #5, is just across the street.

Zoja recounts a harrowing childhood: her father died in prison and was buried without a headstone; her mother was murdered at the train station. She learned to survive the bitter nights and sweltering days. She recalls playing with two girls in the home where my grandparents once lived and how they all left with the other Tatars.

I follow Zoja across the street, stopping to pluck a cherry from her tree. Two girls lounge in the wide, arched doorway of the house where my father spent his early months. A bald Uzbek man with gold teeth opens the door and greets us with a broad smile, clearly delighted by the American visitor.

This is the home my grandparents would have retreated to after my great-uncle passed away in the local jail, just as Zoja’s father did. It is here that they would have read a letter from the mayor of their hometown in Poland, Zamość, responding to my grandmother’s inquiry: The fate of their parents and sisters left behind mirrored the fate of all Jews. The town was Judenfrei—free of Jews.

I choose not to share the pain my family endured in this place. Instead, I smile, sensing that what for my family was marked by hardship is this man’s greatest pride. He tells us the house was a significant investment; he rebuilt it using a blend of mud and straw. I linger in the garden, hesitant to step inside the home. I realize that Zoja, with her vibrant spirit and stories, is the connection to my family’s past that I had longed to find. The renovated house is a testament to this man’s family story. I express my gratitude with the Uzbek gesture of placing my hand on my heart and say farewell.

What was once a distant memory is now a place I have smelled, felt, and touched.

There’s one final place I wish to visit in Juma. In an oral history recording I discovered in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum archives, my grandmother recounted that despite the hardships they faced in Uzbekistan, the women would dress nicely in the evenings and walk along the train tracks with other Polish refugees. We stroll a few blocks to the closed station, with its shuttered ticket office, mint-green chairs, and an empty kitchen.

Like my grandmother, the four other women traveling with her were all young during the war, yet none became pregnant for five years. Eventually, most of them began to show signs of pregnancy. “We already knew the war was coming to an end,” my grandmother remembered. In June 1945, my father was born.

The following summer, my grandparents, with their one-year-old son in tow, boarded a train to Poland, completing a 5,000-mile journey only to find that their loved ones had turned to ashes. They spent another four years in refugee camps across Europe before finally boarding a ship to New York City in 1950.

As we walk away from the train station and cross back over the bridge, the sun no longer bears down on us. During the drive back to Samarkand, I sit in the front seat, enjoying the cool evening breeze, and I feel a sense of relief. What was once just a vague memory is now a place I have smelled, felt, and touched. Juma is where so much heartache took place, yet it also holds joy. I can feel my father's presence, even as I long for more: to experience his excitement at this significant place where he came into the world and to share in his awe at the incredible journey he undertook.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5