Introducing Alaska’s Final Milk Producer

About two hours southeast of Fairbanks, Alaska, on a farm nestled in the wilderness, you can usually find Scott Plagerman, Alaska’s sole commercial dairyman, overseeing his milking robot in action. A bubblegum-pink udder, freshly cleaned, approaches a set of laser-guided suction devices. Adjust left. Adjust right. Lock in place. Then the milk begins to flow.

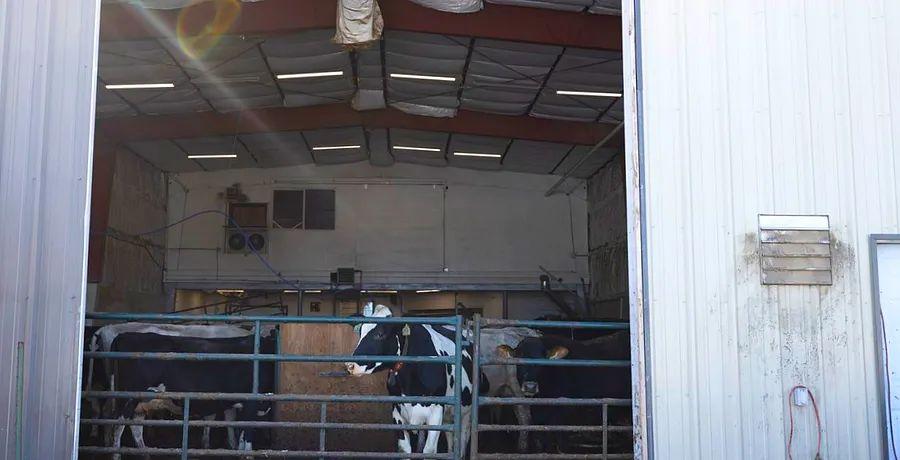

Plagerman’s Alaska Range Dairy is the only source of fresh grade A cow milk in the state. The farm is home to 35 milking cows that reside in a heated barn for seven months each year and graze on grassy pastures during the summer. They produce between 200 to 240 gallons daily, which is a small portion of the state's total consumption, but their market share is on the rise.

Running a dairy farm in remote Alaska is no easy task. It requires growing your own feed, addressing veterinary issues, repairing equipment on your own, and managing the bottling and distribution of your milk. Not to mention the costs associated with keeping cows warm in minus 30 degrees and deterring bears from the fields. Plagerman relishes the challenge of going solo.

“And the payoff, if it succeeds,” he states. “Sometimes it doesn’t.”

Dairying is all Scott Plagerman has ever known, and he’s relying on a niche market in Alaska to sustain his business for the long term. His family has been in dairy farming for at least four generations, most recently in Washington state. Since starting his milking operation in Delta Junction a year ago, he’s discovered a demand from locals who rarely experience truly fresh milk or have never lived near a dairy farm. They’re eager for his mostly grass-fed, nonhomogenized, glass-bottled milk, even at a premium price. He hopes the locavore market, his automated milker, and the relatively relaxed regulations in rural Alaska will keep his business viable in an increasingly challenging environment for small dairies everywhere.

While wild foods like fish, moose, and berries abound in Alaska, the state’s relationship with perishables like winter produce and milk has always been complex. The majority of groceries are sourced from outside the state, with milk and produce needing to travel at least 1,500 miles from Washington to reach Anchorage. Especially during the pandemic, various delays have impacted these shipments. Empty dairy shelves have become a common sight in grocery stores across the state over the past two years, serving as a stark reminder of Alaska’s fragile food security.

Scott and Connie Plagerman at their Alaska dairy farm site.

Scott and Connie Plagerman at their Alaska dairy farm site.Understanding Alaskans' connection to milk reveals key dynamics of the state’s food culture. Geographically and commercially, Alaska resembles an island, largely dependent on outside sources for food. There’s deep pride in the local wilderness and its wild foods, but also a desire to connect with the broader culture of the Lower 48, sharing in its diverse food experiences — from stone fruits and shishito peppers to Trader Joe’s Thai peanuts and In-N-Out Burger. What could be more American than pouring milk over Cheerios or dunking an Oreo in it? Without milk, how would Alaskans define themselves?

Many long-time residents, particularly in rural areas, grew up with powdered and boxed milk, often mixed in old milk jugs as parents tried to pass it off as the real thing. Consequently, many people still have an aversion to it. Others, however, harbor nostalgic fondness for canned milk in their coffee or cocoa. Even before the pandemic's supply chain issues and rising inflation, fresh milk, when accessible, was costly, especially in communities off the road system, which are predominantly Alaska Native.

“In the villages, there’s virtually no access to refrigerated milk,” states Sarah Coburn, an assistant state veterinarian who collaborates with dairies. When she first relocated to Alaska, she lived on the North Slope, a remote area in the northern part of the state where travel is primarily by small plane. Fresh milk may be available, she notes, but it could be nearing its expiration date and priced at $10 or $12 a gallon.

The tendency Plagerman noticed — the willingness of people to pay a bit more for milk that hasn’t traveled hundreds of miles — mirrors the motivations of Presbyterian church women in Fairbanks who compiled recipe books for white cakes a century ago, despite the difficulty of sourcing butter, sugar, fresh eggs, and white flour. There’s a certain magic to the novelty and a sense of validation in having direct access to it.

Before the arrival of non-Native peoples, Alaska Native diets did not include dairy. However, milk held significance for early white prospectors and missionaries who brought it to Alaska Natives. During the Gold Rush, it was a crucial part of supply packs, despite its weight and cost (canned condensed milk was pricier than liquor at that time). “It served as both a quick energy source — packed with calories and sugar — and a reminder of the lives they had left behind,” explains David Reamer, a historian based in Anchorage.

In the early 20th century, many small dairies, each with just a few cows, opened and closed in early Anchorage. The challenge of sourcing fresh milk in Alaska, both then and now, is that local production costs have never been able to compete with the lower costs found Outside, where grain is cheaper and larger commercial dairy operations yield much grMytour volumes, even when shipping costs are factored in.

Plagerman emphasizes that his automated milking machine is crucial to the operations at Alaska Range Dairy.

Plagerman emphasizes that his automated milking machine is crucial to the operations at Alaska Range Dairy. Alaska Range Dairy's milk is priced higher than that which is shipped over long distances, but enthusiasts believe it’s worth the extra cost.

Alaska Range Dairy's milk is priced higher than that which is shipped over long distances, but enthusiasts believe it’s worth the extra cost.“The economies of scale that allow milk production in the Lower 48 simply can’t be matched here,” Reamer explains. “Everything is too small and too fragmented.”

Matanuska Maid, a state-run dairy that purchased raw milk from small farmers north of Anchorage, closed its doors in 2007 after 71 years due to an inability to maintain competitive milk prices. The smaller Matanuska Creamery followed suit, shutting down in 2012 after failing to provide farmers with adequate payment for their milk. Most recently, Havemeister Dairy, a large supplier to grocery stores, ceased operations late last year because of labor shortages, high land costs, and aging equipment.

“In the Lower 48, it’s hard to fully appreciate how different things are. There’s much more support for small farms,” notes Coburn. “In Alaska, with far fewer people and farms, the commitment to producing and serving the community is truly remarkable.”

Plagerman and his family — wife Connie and children Kyle, Jessica, and Cody — relocated to Alaska in 2008 to take over a remote farm near Delta Junction. With a population of 1,000, Delta lies deep in Alaska’s interior, where summer temperatures can soar into the 90s with nearly continuous sunlight, and winter temperatures plummet well below zero, accompanied by deep snow and short days. They initially grew hay for the equestrian market before starting their dairy, and they also maintain a small herd of bison.

The Plagermans moved north as urban sprawl and land use regulations began to encroach on their operations. “They were pushing small farms out of business,” Plagerman explains. “I want to emphasize that government regulations are stifling family farms, even while they claim to support them.”

Fortunately, Delta offers ample land and significantly less government interference.

Connie Plagerman and a neighbor fill glass bottles by hand three times a week.

Connie Plagerman and a neighbor fill glass bottles by hand three times a week.“Population and farms don’t mix well, which is crucial. We don’t face population encroachment, and it doesn’t seem likely for a long time,” he states.

Aside from the Plagermans, the only other commercial dairy in Alaska is on Kodiak Island, where they sell goat milk.

“The major expenses for a dairy — feed, labor, and energy costs — are challenging everywhere, but in Alaska, you multiply those costs by two, three, or even four,” Coburn explains.

Plagerman’s cows are fed a mix of local grain and hay. The growing season in Alaska is quite brief, allowing for only one hay cutting each year, unlike the multiple harvests possible in many Lower 48 states. Supplements and machine parts must be shipped in. If a milking machine breaks down, cows must be milked by hand or an alternative system has to be ready until the necessary parts arrive. Though the Plagermans brought valuable experience to Alaska, they still had to employ ingenuity to bring their milk to market, according to Coburn. Most dairymen Outside primarily focus on raising and milking cattle, rather than processing dairy products.

“He’s a lifelong dairy professional, but he had to master processing and bottling, which typically isn’t handled by one family,” she explains. “Those tasks are usually divided among various companies and facilities.”

Plagerman asserts that technology enhances his farm's competitiveness. His barn features a heated floor, and manure is removed by a machine similar to a large Roomba. Most crucially, he utilizes a milking robot. Each cow is fitted with a monitor that tracks various data points, including milk output, quality, and any signs of illness.

“It’s akin to a Fitbit. It keeps tabs on their movement and digestion,” he remarks.

When the cows are ready to be milked, they approach the machine and nibble on grain while the system does its job.

“The robot is essential for our dairy operation here since we lack sufficient labor to have someone milking the cows full-time,” he explains.

During the winter months, the cows reside in a temperature-controlled barn.

During the winter months, the cows reside in a temperature-controlled barn. Plagerman’s cows are fed a diet of hay, grains, barley, and peas.

Plagerman’s cows are fed a diet of hay, grains, barley, and peas.Plagerman’s cows are quite sociable, with names chosen by his daughter, such as Doris, Rachel, and Tina. On a snowy April day, they munched on hay in the barn, which was open on one side for fresh air. Nearby, a pen held three calves, their heads poking out as they searched for a meal.

The cows enjoy a diet of hay and grains that Plagerman cultivates on his land, including barley and peas; corn isn't suitable for the local climate. Their milk is pasteurized at a lower temperature for a longer time compared to larger dairies, resulting in a creamy layer on top, ideal for adding to coffee. Some customers who are sensitive to dairy find it easier to digest due to the lack of homogenization.

Three times weekly, Connie Plagerman and a neighbor wear white coats and hairnets as they begin the bottling process. They fill a machine with 800 gallons of pasteurized milk, which dispenses it into clear glass bottles topped with red caps. Each bottle is dated and placed in a cooler for transport to stores. While the milk hasn’t reached many large grocery chains yet, it’s available at smaller outlets like health food stores and local groceries, with the aim of becoming a specialty item in larger stores.

Alaska Range milk is a premium product, sold in gallon jugs or half-gallon glass bottles priced between $5 and $8, depending on the location, plus a $3 bottle deposit. In urban Alaska, commercial milk prices vary from about $4 per half gallon to nearly $7 for organic, grass-fed options. This slightly higher pricing has been a challenge for many dairies in Alaska.

“The milk market has been favorable, but we’ve noticed in recent weeks that due to economic factors, including gas prices, people are cutting back a bit,” Plagerman notes, referencing the market fluctuations tied to the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. “The milk is more expensive because it costs more to grow grains here. In my opinion, it’s a superior product, but at some point, people prioritize price over quality.”

Plagerman samples his milk with the same care a vintner applies to wine tasting. A sip of Alaska Range Dairy milk envelops the palate with richness, a hint of salt, and a subtle, pleasing earthiness. In most cases, small farmers' milk gets combined with that from larger dairies to balance out minor flavor variations, but this practice isn’t feasible in Alaska.

“The challenge with small dairies is that we can’t blend milk from multiple farms to standardize flavors, so we must be extremely mindful,” he explains.

Interestingly, this distinct flavor is often a key selling point.

“Whatever they’re being fed clearly affects the flavor. It’s just genuinely whole milk,” says Jessica Johnson, co-founder of Blue Market, a small Anchorage grocery that emphasizes bulk and reduced packaging. Since last fall, she has stocked Alaska Range Dairy milk, attracting customers who regularly return to pick up and exchange bottles. They appreciate how the milk is packaged, she notes, and the unique flavor has garnered its own following.

Alaska Range Dairy milk is available in specialty markets and gourmet shops throughout Anchorage.

Alaska Range Dairy milk is available in specialty markets and gourmet shops throughout Anchorage.Johnson, an Alaska native, describes a sense of being distant from the abundant food options available in the rest of the country — a feeling that prompts many Alaskans to bring back rare foods in their luggage when returning from trips to other states.

This might explain why, when Drew Harlos and his wife Jennifer tried Alaska Range Dairy milk from Blue Market for the first time, they eagerly opened it in their car. It simply felt authentic, he remarked.

“It smelled like real milk, if that makes sense,” he shares. “The milk we usually buy is nearly tasteless compared to this.”

The Harloses took the opportunity to explain to their kids that this milk originated from cows right here in Alaska. Many children in Alaska seldom connect fresh grocery items with their origins. “I have a 4-year-old and a 2-year-old, and we’ve been trying to teach them about milk and farms. I said, ‘This milk comes from here; there are cows here,’” he recalls. “That’s a lot different from saying, ‘Here’s a big jug, and I don’t know where it’s from.’”

Plagerman is counting on more customers like the Harloses to discover his milk and appreciate its worth in such a remote area far from other dairies.

“We hope to expand to more stores; getting into larger ones is crucial,” he explains. “We want to raise awareness about our product.”

If things go well, he hopes to pass down his farm to his children, just as previous generations of dairymen have done.

Julia O’Malleyis a third-generation Alaskan, an editor, and a James Beard Award-winning writer based in Anchorage.Nathaniel Wilderis an Anchorage-based photographer passionate about all things Alaska.Fact checked by Victoria PetersenCopy edited by Paola Banchero and Nadia Q. Ahmad

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5