Mules, Ranchers, and Gorges: An Expedition to the Timeless Murals of Sierra de San Francisco

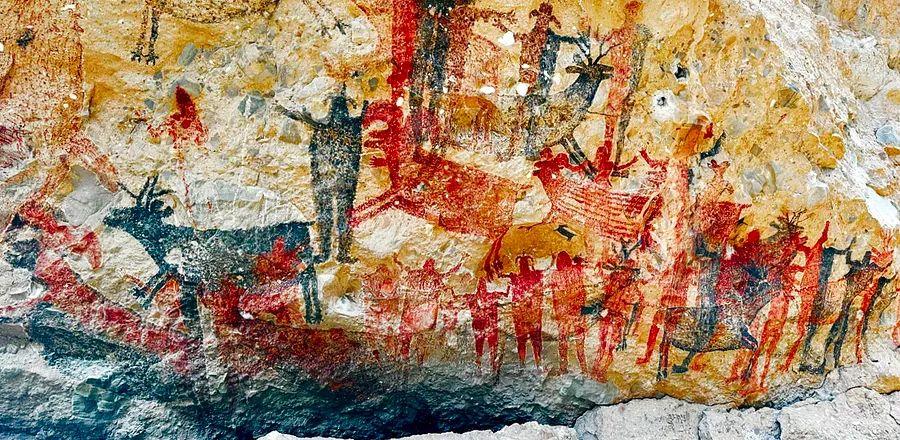

Primitive revelers. That’s how these imposing nine-foot figures struck me when I first encountered them last fall. Exquisitely crafted in vivid red and black, with arms raised high, they seemed to twirl joyfully, as if enchanted by some grand, cosmic DJ.

I first stumbled upon the Great Murals of the Sierra de San Francisco in 1997, a time when the rave scene was undeniably captivating my thoughts. Back then, I was teaching English in Villahermosa, Tabasco, and the enigmatic artworks felt frustratingly distant. They were a thousand miles away—nestled in a canyon deep within the Baja California Peninsula—and I lacked the time and means for the journey. I marked the pertinent page of my Rough Guide with a bold, red star and promised myself I would visit one day.

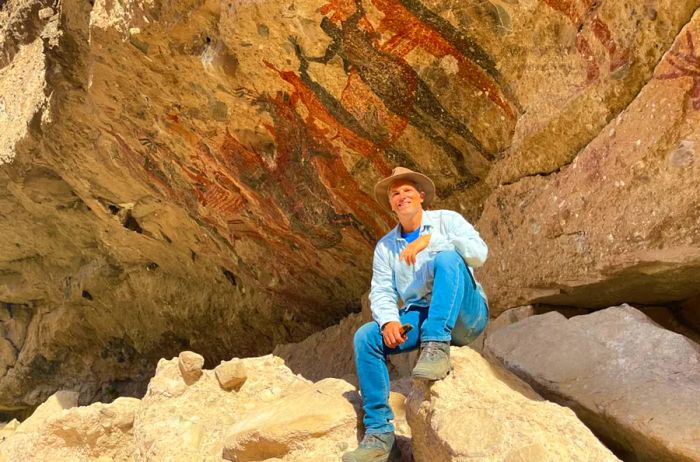

It took me a quarter-century to fulfill that pledge. But last November, I found myself in Loreto, greeting anthropologist Orloff Nagorski: my companion for the upcoming six days. Orloff, the director of Aventuras Mexico Profundo, has been conducting tours to the murals since the 1990s.

“You’re about to witness some of the finest rock art globally,” he remarked, brimming with pride. “If you visit Lascaux in France or the prehistoric murals in Spain, you’ll encounter only reproductions. But these are the authentic masterpieces, remarkably well-preserved.”

The Great Murals represent the oldest cave art in the Americas, dating back between 7,000 and 12,000 years as per carbon dating. They are primarily credited to the Cochimí tribe and their ancestors. However, like much about these ancient masterpieces, this attribution remains largely unverified.

Historical records about the Cochimí are scarce: they were semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers inhabiting the central part of the peninsula during European contact. Writer and adventurer Harry W. Crosby noted: “For those living in the central desert, movement was essential. No area could sustain a large population year-round, not even the coastal regions. . . . They relied entirely on the seasonal availability of fruits, seeds, stems, and roots. In ancient times, the primary goal of Cochimí men was hunting deer, sheep, and antelope—their only meat source.” The first comprehensive accounts come from the Jesuits, who founded a small monastery in Loreto in 1697. Some of these writings are distressing. For instance, Father Johann Jakob Baegert described the Cochimí as: “dimwitted, dishonest, thieving, and horrifically lazy.” Baegert provides no insight into the tribe’s spiritual beliefs, omitting their “absurd and superstitious rites” “for reasons of decency.”

Similar to “The International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs” in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899), the Jesuit order sought to replace any indigenous belief systems with their own. They introduced Catholicism to the area, but they also brought disease. Seventy-five years post-arrival, the Indigenous population had plummeted by 90 percent. By the late 19th century, the Cochimí had completely vanished.

The mission bells rang throughout the night, but it hardly mattered. Today, I was to embark on my journey to San Ignacio: the starting point for my long-awaited expedition. I was accompanied by Orloff, his wife Janet, and two other travelers, Allen and Chuy. As we navigated Highway 1, we passed through the heart of Baja: the traditional land of the Cochimí.

Ospreys perched on telegraph poles while hawks circled menacingly above. The road south of Mulegé had been torn apart by a recent hurricane. Our van bumped over the uneven pavement as we traveled north, hugging the shoreline of the Sea of Cortez. Native tribes had fished these waters for thousands of years: turtles, manta rays, and sea lions are all depicted in the Great Murals.

As we drove along, Orloff shared that the origins of the paintings likely trace back to the ancestors of the Cochimí, who are thought to have arrived on the peninsula around 12,000 years ago. Following this initial creation, it appears that subsequent generations added layers and embellishments to the murals. Compounding the enigma of their origin, the Cochimí claimed to the Jesuits that the artists were a tribe of giants hailing from the north.

We reached San Ignacio just in time for my Zoom meeting with Maria De La Luz Gutiérrez Martinez, a senior archaeologist at INAH (National Institute of Archaeology and History). Martinez oversees the management of around 600 archaeological sites in the Sierra de San Francisco. She has been investigating the Great Murals since 1981 and is recognized as one of the foremost experts in the field. In 2014, she received the prestigious Alfonso Caso Award for her doctoral thesis: “Ancestral Landscapes: Identity, Memory and Rock Art in the Central Cordilleras of the Peninsula of Baja California.”

“The Cochimí lacked a written language, making these paintings their sole record,” she explained. “It is the responsibility of INAH to safeguard them.”

Maria revealed that the Great Murals were created as an expression of ancestor reverence, with the headdresses on the human figures symbolizing different family lineages. The Jesuits systematically obliterated Cochimí ceremonial artifacts, including guanakaes—sacred garments made from human hair. The tribe’s traditions, lifestyle, and attire: all of it was wiped away.

When the Sierra de San Francisco was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1993, INAH initiated the Sierra Management Program, establishing specific regulations for visitors. The number of guests and group sizes are restricted, and all excursions necessitate permits and are overseen by the rancheros, who have inhabited the Sierra de San Francisco for generations.

Photo credit: Edmund Vallance

The next day, I was set to meet three of these rancheros, the guardians of the Great Murals.

“I view them as the original Californians: the direct descendants of ranchers who fled persecution in Spain,” Orloff remarked as we traveled toward Rancho Guadalupe, a small desert outpost near the canyon's entrance. We drove north on Highway 1 for 28 miles before turning east at a worn sign reading "San Francisco." That other California—the one filled with celebrities and tech moguls—felt astonishingly distant. Suddenly, the pavement vanished, and we seemed to be gliding on a magic carpet made of rust-colored dust.

The road constricted, and the valley dropped steeply to our left. After a quick stop to collect our permit, we reached the ranch and met our guides: Jesus (22), Ramón (54), and Gertrudis (70). The men swiftly secured our luggage onto a line of donkeys and mules, and we began our three-hour descent into the canyon. I opted to walk along a narrow, winding path carved into the steep mountainside. Vultures circled above, and I lost my footing on the loose rocks, jabbing my hand on a stray cactus paddle. I decided to try riding a mule, but the unfortunate animal brayed and swayed, perilously close to plunging into the sun-baked ravine, 500 meters below. My Harrison Ford fantasy was quickly fading. I felt like a city boy in a sombrero, an impostor in double denim.

By the time we hit the valley floor, I was trembling, my jeans soaked with mule sweat. Towering cliffs surrounded us, and a full moon glowed like gaudy Vegas lights. Politely passing on a tequila shot, I stumbled into my quickly set-up tent, cocooned myself in a sleeping bag, and drifted off, fully dressed.

If the canyon had appeared nightmarish under the moonlight, by morning it transformed into a paradise. Yellow brittle bush, purple marisol, and enormous barrel cacti emerged from every nook of the campsite, each petal and thorn glowing in vivid detail. The air was so pure, it felt like fire in my lungs.

“I’d love to offer you pancakes,” Orloff said, “but a donkey raided our cooler last night and devoured them all.”

Photo credit: Edmund Vallance

After breakfast, our group of eight mounted our mules and set off down the parched riverbed. Fifty-foot palms danced gently in the breeze, and powder-pink boulders dotted our route like pieces of cherry candy. These arroyos served as the Cochimí’s highways during the hunting season, and some of these stones were used to create paint for the murals. For red, they crushed iron oxide; for yellow, they utilized sulphur compounds; and for black, they ground volcanic rock.

“We repaint our houses every 5 to 10 years,” Orloff noted. “But this paint has endured for 10 thousand years. Just think about that.”

I did, but it was giving me a headache.

“Look!” exclaimed Jesus, gesturing with his reins. “La Cueva Pintada!”

This was the location that Harry W. Crosby described as: “the most painted section of the entire range of the Great Murals . . . the center of the phenomenon.” I had relished his book, The Cave Paintings of Baja California (1975), but no amount of reading could prepare me for what lay ahead.

Shielding my eyes from the glaring sunlight, I noticed a wide rock ledge dotted with numerous black and red figures. The artwork wound along over 200 meters of the canyon wall, elevated above a shimmering oasis. For a fleeting moment, I envisioned Monty Python’s hand of God breaking through the sky.

Climbing up the slippery slope on our hands and knees, we eventually reached the ancient gallery. Six clusters of murals decorated the walls, each appearing more breathtaking than the last. Pumas, coyotes, antelope, and various desert creatures vied for our attention. The human figures seemed like blood-red visions, shifting and transforming in the bright morning light. Being so close to the Great Murals, with no other visitors around, made me choke back tears.

“The hallucinogenic plant, datura, grows abundantly in this area,” Orloff explained. “The Cochimí likely utilized the flowers to induce altered states, along with repetitive music and dances. Notice how their arms are lifted above their heads in a ceremonial dance, a state of ecstatic flight.”

Maybe my raver theory wasn’t as absurd as I initially thought.

Photo by Edmund Vallance

“What do you think, Gertrudis?” I inquired. “What significance did these images hold for the Cochimí?”

The ranchero examined the paintings carefully, his thumbs tucked into his jean pockets. He lingered in silence for so long that I began to doubt he would respond at all.

“Well,” he finally replied, adjusting his sombrero with his index finger. “The tribe observed the animals in the valley. Then... later... they painted them on the wall...

“That’s all there is to it,” he concluded.

I wished I could linger longer. However, time was slipping away. We had to reach La Cueva De Las Flechas (“Cave of the Arrows”) by four o’clock to ensure we could return to camp before sunset. Rattlesnakes and tarantulas were among the hazards that necessitated this urgency.

Luckily, the second cave was situated directly across from the first. We scrambled down, then up again, and within 20 minutes, we arrived: standing before another prehistoric showcase. The site was much smaller, yet the figures were fluid and intricate, exuding the elegance and solemnity of a medieval tapestry. Above the depiction of a deer, a human figure was pierced by arrows, resembling a Stone Age Saint Sebastian.

We never discovered any arrowheads; no Temple of Doom relics. Hollywood bombards us with golden idols, hidden chambers, and human sacrifices. But the Cochimí had none of that. Their legacy was their art: captivating images that resist clear understanding. The painted figures gaze down at us from Dinogo—defiant, distant, and inscrutable.

I’m neither an archaeologist, anthropologist, nor a member of an Indigenous tribe. I’m just a writer who cherishes Mexico, a middle-aged man with a laptop. Yet, the Great Murals resonated with me profoundly. They pulled me in like an electrifying rave beat or the verses of a sharp folk ballad. Were these creations the result of hallucinogenic shamanic visions? Tributes to ancestors? Or merely artistic embellishments, akin to primitive wallpaper? The reality is that no level of contemplation will ever yield a conclusive answer. Their beauty remains the sole certainty.

These reflections swirled in my mind as we made our way back to camp that evening. When our joyful group finally settled down to eat, Ramón serenaded us with his rich, wavering baritone voice:

“I’m unsure of my destination.

And I can’t predict where I’ll find myself.

All I desire is to immerse myself in the wonders of this life.

The splendor of this canyon!”

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5