Once exclusive havens for women, these sites are now recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Ghent is a picturesque city of canals, adorned with vibrant floral displays on its bridges. The Gothic buildings rise majestically like intricate sandcastles against the skyline. As I traverse the cobblestone streets, cyclists rush past, and the bells of St. Bavo’s Cathedral resonate. I've journeyed a great distance and risen early to explore this first beguinage, a historic site that once sheltered spiritual laywomen known as beguines.

Our-Lady Ter Hooyen, affectionately called 'the little beguinage,' was originally established in 1234, though much of what stands today was built five or six centuries later. This classic court beguinage is encircled by a tall white wall with a single gated entrance. By the mid-13th century, many major cities in the Low Countries had their own beguinages: enclosed communities of adjoining buildings fortified by high walls and sometimes moats. This layout was designed for privacy and to deter intruders, as women living or walking alone were often vulnerable to male assaults. Beguinages secured their gates nightly, and leaders typically required that members only leave in pairs. While the informal nature of beguinages means we can't ascertain the total number that existed, at their peak, there were tens of thousands.

I first discovered the beguines in 2016, during my quest to align my life more closely with my values. Having been in consecutive monogamous relationships from ages 15 to 35, I found myself independent and ambitious in my roles as a writer and professor, yet my life had always been defined by my connections with romantic partners. I didn't truly know myself alone, and I felt increasingly that I was missing something. My journey into abstinence began with a three-month period, which I referred to as celibacy, unsure of how else to label it. I completely distanced myself from any form of romantic or erotic intimacy—no dating, no flirting, no intense friendships.

Initially, I believed celibacy was marked by deprivation and driven by asceticism—a dry, prudish impulse. However, that period turned out to be one of the most sensuous and intimate of my life. As it unfolded, I delved into research on female celibacy to better understand my experience. I read the ancient Greek play Lysistrata, which explores sexual desire, along with pamphlets from radical feminist groups. I studied the Shakers, the teachings of Father Divine—whose followers embraced abstinence—and the Dahomey Amazons, an all-female regiment in what is now Benin. Yet, no celibate women resonated with me more profoundly than the beguines.

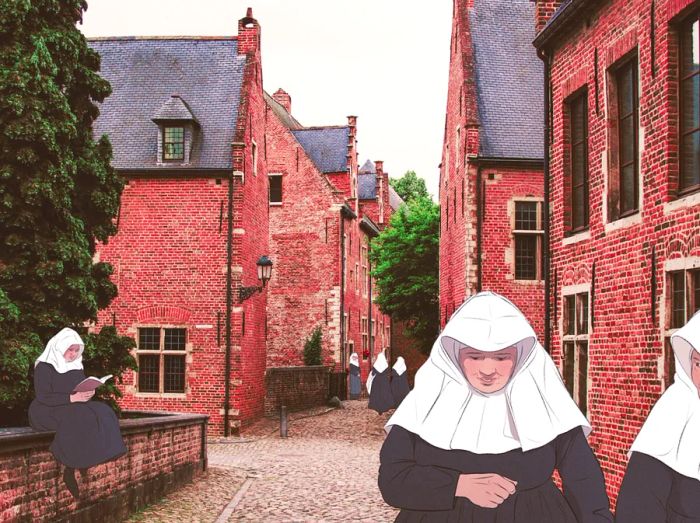

I was enchanted by these religious laywomen and their dedication to independence. Instead of conforming to the societal expectations of marriage, children, and housework, they lived in community, earned their own incomes, and devoted their lives to service. So inspired by them, I embarked on a pilgrimage to Belgium’s Flanders region, home to the largest number of former beguinages. Thirteen of these sites are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites, deemed "havens of tranquility" with "simple functional architecture that creates a unique atmosphere of utopia, balancing community and respect for individuality," according to UNESCO. These beguinages—now primarily residences and monasteries—draw thousands of visitors each year. Six years later, I have returned once more.

Within the confines of this quaint beguinage lies a graceful courtyard bordered by lime and beech trees, encircled by the homes of the beguines, all secured by another white wall connecting small green doors, some adorned with tributes to Catholic saints. The buildings, now providing subsidized housing, are constructed from red brick with white trim. Through the windows, I catch glimpses of daily life: neatly arranged dishes and a bowl of fruit.

Capturing the essence of this place is more challenging. I arrive just as the sun begins to rise, illuminating the cobblestone paths and casting shadows from tree branches onto the walls. It is tranquil, save for the gentle rustle of leaves. I relish my solitude and ponder how much more precious this moment would have been 800 years ago. I envision the woman who once stood here, defying societal norms to embrace a life free from children and a husband.

My fascination with the beguines has always seemed an unusual interest for a queer memoirist and college professor who lacks religious affiliation. Now married and fresh from publishing my fourth book, I find myself returning to them. Why do I still feel drawn to this medieval order of laywomen? What lessons can they impart to me now? These inquiries have brought me here, and the emotions I experience in this courtyard feel like a significant clue.

Unlike nuns in the Middle Ages, who typically hailed from wealthy families able to afford the necessary dowries for abbeys, beguines originated from all walks of life. Any woman could join. Beguines did not take permanent vows; instead, they made promises similar to those of nuns—always of chastity and obedience, with other commitments varying by community. These promises could be relinquished or reinstated at any time. Women could leave beguinages to marry or bear children and were welcomed back, albeit without their families. Sister Laura Swan, a Benedictine nun and author of The Wisdom of the Beguines, explained that joining the beguines provided a woman an opportunity to escape from a husband she no longer wished to have.

Marie d’Oignies (1177–1213), the Belgian mystic saint, is frequently recognized as the first beguine. However, there is no officially acknowledged founder of the movement, and its exact beginnings are elusive, as communities emerged simultaneously in various locations. The rise of beguine communities was fueled not only by the increasing religiosity across Europe and the larger male population but also by the growing literacy movement. In the early 13th century, two countess sisters from Flanders invested in secular coeducational schools, convinced that education would enhance the economy. This initiative inspired other European leaders to follow suit.

Illustration by Isabel Seliger

Consequently, from approximately 1200 to the 1600s, the beguinal movement flourished throughout northwestern Europe. The term movement—is particularly fitting, as it not only captures the swift expansion of their communities but also reflects their achievement of independence, social transformation, and sustainable communal living—goals that have been pursued by many subsequent women's movements. Scholars have identified 111 medieval beguinages in Belgium alone, many of which once accommodated hundreds of residents while maintaining their independence through shrewd business practices.

Each beguinage functioned autonomously, with its members often holding jobs beyond its walls. Many communities also operated their own businesses—frequently in textiles or laundry services—since financial independence was crucial for beguines; their economic acumen allowed them to remain free from clerical authority. Beguines provided care for the sick and dying, and they managed orphanages, hospitals, and educational institutions.

The beguines were also deeply engaged in spiritual work, believing that everyone could establish a direct connection with God. During their time, the Catholic liturgy was performed in Latin, making it accessible only to male clergy and scholars. The beguines championed the idea of unmediated access to spiritual texts and teachings, leading them to preach in the vernacular, compose their own meditations, and translate the Bible into everyday language—bold initiatives for laypeople, especially women. They perceived spiritual truth as an all-encompassing love that expressed itself physically, emotionally, and through daily practices. Inspired by the 12th-century French concept of romantic love popularized by troubadours, the beguines often referred to God and divine experiences using the feminine term Love.

I inquired with another expert on the beguines, Silvana Panciera, about her fascination with them. "Because I felt in them the root of my history," she explained. "The foundation of feminism... they took the first step towards independence." Silvana has dedicated nearly 30 years to studying the beguines, authoring a book, adapting it into a documentary (All Om All), and making her research available in several languages.

Researching the beguines poses more challenges than investigating more formal religious movements. This is partly due to the neglect of female monasticism by male historians and partly because the beguinal movement was repeatedly suppressed by the Catholic Church, which labeled them as heretics. Despite these adversities, the "gray women"—named for their modest dark cloaks and headdresses—enjoyed greater freedom than most women throughout history. They appeared to live more authentically according to their convictions than many people I have encountered.

It is often noted that the last beguine, Marcella Pattyn, passed away in her beguinage in Kortrijk, Belgium, on April 14, 2013. However, many, including Swan, believe that a modern movement is emerging, with communities flourishing in various countries, including the United States, Canada, and Germany. Yet, when it comes to history, there truly is no place like Belgium.

The train ride from Ghent to Bruges is brief, followed by a 15-minute stroll from the station to the beguinage. Known for its beauty, Ten Wijngaerde, a Benedictine abbey since 1927, is among the most photographed beguinages globally. The main entrance is accessed via a stone bridge, leading into a complex of houses constructed between the 16th and 18th centuries. Throughout the courtyard, signs remind visitors to maintain silence. In the expansive gift shop, somewhat grumpy elderly women sell figurines and crucifixes.

I push open the sturdy door of the church. Although I haven’t been a regular attendee, the interiors of such buildings have always moved me. This church may not be lavishly decorated, but as the door gently closes behind me, I take a deep breath, gazing at the white ceilings, the rows of red votive candles, and the floral arrangements before the altar dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

Even though this isn’t my place of worship, sitting in one of the wooden pews makes me feel at ease. I light a candle and leave a donation. As I step back into the courtyard, the daylight has waned, and I start heading back to the train station. Years have passed since I let go of my vow of chastity, yet I realize I’ve retained a sense of that period: a feeling of belonging not to anyone else, but to myself and my own calling. I think of my wife, and the mutual respect and autonomy that enrich our relationship. Like me, she is an artist, understanding the independence needed to live fully realized lives together. I wouldn’t have been capable of such a relationship—choosing it or nurturing it—if I hadn’t taken the time to reflect. If I hadn’t contemplated the beguines, whose lives were grounded in principles of independence, creativity, service, and love.

Years have passed since I let go of my vow of chastity, yet I realize I’ve retained a sense of that period: a feeling of belonging not to anyone else, but to myself and my own calling.

After visiting Bruges, I head to Brussels to meet Graham Keen. He is an English retiree who conducts tours of beguinages throughout Belgium, where he now resides as a citizen. He translated Panciera’s book into English, and she is the one who connected us. In an email, she referred to Keen as a beghard—the term for a male beguine; they were few in number and eventually became part of formal monastic orders. On the train to Mechelen, he speaks of his wife and son, leading me to wonder if there’s been a misunderstanding.

In Mechelen, we stroll through the charming village center towards a neighborhood marked by tall white walls that feel familiar. Like others, the beguinage is a meticulously preserved historic site with private residences and a few commercial establishments. Keen highlights the impressive magistra’s quarters and shows me photographs of it before the bricks were painted. We admire the medieval doorways and then enjoy lunch at Het Anker, a historic brewery founded by the beguines in 1471, which was acquired in 1872 by the family that still operates it.

Our last destination is the church, its interior adorned in pastel colors and filled with wooden prayer desks once utilized by the beguines. As I stand there, I recall the end of my previous conversation with Panciera. "I believe you are someone in search of profound love. Am I correct, Melissa?" she inquired.

"Yes," I replied, reminiscing about the years I spent seeking it in others. I initially arrived here yearning for a different kind of love—a connection to myself that transcends romance. Now, standing in the church, I feel it within me, like an echo of the past that resonates, reminding me of deep roots and an ancient urge to live with purpose and compassion.

I ponder that Keen and I might seem like an unusual pair—me, a petite American in athleisure, and him, a tall British man 30 years my senior—as we make our way back to the village center, where a train awaits to take me to Leuven. We enjoy coffee together, discussing his children and grandchildren, and my students. Panciera was right: Keen embodies the essence of a beghard. Though married, he has crafted a life that reflects beguine values, nurturing his passions and good work with the same care, humility, and consistency one shows a cherished friend.

We walk the last few blocks to the train station, shaking hands before parting ways. As my train departs, I realize that the comfort I share with him mirrors what I've felt with Panciera and Swan. Our shared enthusiasm for the beguines unites us, despite our evident differences. Like the gray women, we are driven by a thirst for meaning.

Later that day, I find myself in Leuven, standing in the Groot Begijnhof. Established in 1232 and acquired by the Catholic University of Leuven in 1962, it has been meticulously restored. The arched doorways display plaques announcing faculty lounges and academic departments, while students ride bicycles along the cobbled paths. It feels fitting that these spaces are now places where women can live, learn, and teach independently.

This time, instead of envisioning myself in the past, I picture introducing this place to the beguines. As Panciera noted, “They embody our history, our roots of emancipation, and our independence from male authority.” I reflect on how my creative expression is a continuation of their vision. I write about feminist and spiritual themes and translate histories like that of the beguines for audiences who might not encounter them otherwise. I realize this is the most effective way to maintain my connection to them and to the lineage of independence and creativity to which I feel deeply connected.

In The Wisdom of the Beguines, Sr. Laura details the common practice of beguines’ vitae: autobiographical narratives typically recorded by their confessors, where the narrative and its moral significance take center stage. She describes them as “accounts of women’s quest for a true self, articulating the journey of self-discovery and inviting others to partake in that exploration.” Reading this, I was struck by how accurately it encapsulated my own work. It reminded me of standing beneath the trees in that first courtyard, expecting to feel like an outsider, only to discover a profound sense of belonging.

Evaluation :

5/5