Project 562 Will Change Your Perspective on Native America

My name is Matika Wilbur, and I belong to the Swinomish and Tulalip Tribes. A decade ago, I sold all my belongings, packed my bags, and set out on a Kickstarter-funded journey to visit, connect with, and photograph over 500 tribal nations. Throughout this adventure, I learned many invaluable lessons, the most crucial being: We are on Native land. My latest book, Project 562, captures the stories and faces of countless individuals I encountered along the way, with select excerpts featured in the following pages.

North America is Indian Country. The first peoples of America have a profound connection with its lakes, rivers, cities, estuaries, canyons, and mountains. Yet, the mainstream narratives shared with American children often neglect this reality—as reflected in the songs we teach, the holidays we observe, and the romanticized portrayal of Hawai‘i as a paradise vacationland (rather than an illegally annexed kingdom), among many others.

Collectively, these narratives contribute to a historical forgetfulness that dismisses treaty rights, undermines Indigenous sovereignty, and disregards Indigenous nationhood. My mission is to highlight the richness, resilience, and joy of contemporary Native peoples, thereby challenging the outdated and racist invisibility that has long affected our communities.

As we journey across the country in search of adventure, let us do so—as we say in Indian Country—in a good way. What does that entail? It involves educating ourselves about the historical roots of the lands we visit. We learn the Indigenous place names. We adopt Indigenous values in our daily lives, including the principle of “seven generations,” which guides us to consider the impacts of our decisions on the seven generations before us and the seven that will follow. We should ask ourselves: How can I leave this place better than I found it? Can I support the Indigenous economy of the area I’m visiting? Or even more importantly: Is my presence here causing disruption?

A prime instance for travelers to reflect on these questions arises when contemplating a hike along the Nüümü Poyo (the People’s Trail), which settlers refer to as California’s John Muir Trail. This trail traverses lands historically inhabited by the Ahwahnechee, Paiute, Miwok, Mono, and other Tribes. It served as a link between inland and coastal communities, both of whom were displaced by a Congressional act supported by John Muir, often hailed as the “Father of the National Parks.” This reverence fails to recognize the profound trauma he instigated. Many Native individuals still lack access to the Nüümü Poyo, as obtaining a permit requires a lottery, forcing them to compete with the throngs on one of the most frequented long-distance hiking routes in the American West.

The lingering effects of colonization are both catastrophic and immeasurable. I believe that each of us has the ability to help counteract these systemic injustices. In our own small ways, we can all commit to responsible travel and contribute positively amid our adventures.

Photo by Matika Wilbur

Paula Peters

Mashpee Wampanoag

Massachusetts

I encountered Paula Peters on the legendary shores of Cape Cod, a locale that holds a prominent place in the American imagination as a stunningly beautiful and exclusive retreat for the affluent. However, the Cape reveals a different narrative when seen through the lens of Indigenous perspectives. This breathtaking coastal region is, in fact, situated on the ancestral territories of the Wampanoag people, a Nation known for its first encounters with European settlers.

Paula worked with Mayflower 400, a retrospective multimedia initiative that celebrated the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower’s arrival in North America. “For nearly four hundred years, they have attempted to erase our existence from the land, not realizing how futile that is,” she shared with me. “We are the land, and the land is us, and we are still present.”

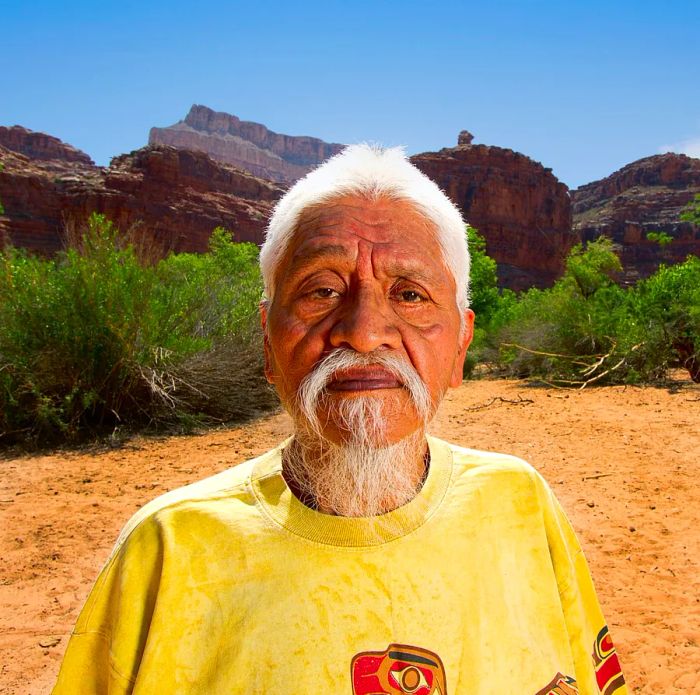

Photo by Matika Wilbur

Rex Tilousi

Havasupai

Arizona

Rex Tilousi, a member of the Havasupai Tribe, recalls, “One of them came down and identified himself as the Great White Father who resided in the big White House to the east. He said, ‘You live in a breathtaking place where Mother Nature has truly worked her magic. We are designating this area as a national park, and you are not permitted to venture beyond the boundaries we set around this canyon.’

“We continue to advocate for these matters and to fight for our rights. The songs sung by the floodwaters are still performed, and we dance to that music even today.

“What I wish to share with those interested in learning about a place known as the Grand Canyon is some history about what we have lost—our language, our songs, our springs, the rock writings, and the caves. For us, this is our Grand Mother Canyon.”

Photo by Matika Wilbur

Fawn Douglas

Las Vegas Paiute

Nevada

Fawn Douglas stands in front of the iconic “Welcome to Fabulous Downtown Las Vegas” sign, adorned in a traditional Jingle Dress. While many may not associate Las Vegas with Native heritage, for Fawn, it is her ancestral homeland and the heart of the Las Vegas Paiute community. Most tourists are unaware that the Nuwuvi or Paiute people are the original stewards of this land. Fawn noted that Las Vegas would not have become the vibrant city it is today without the Nuwu—the Southern Paiute term for “the people.” Moreover, Fawn’s grandfather, Raymond Anderson (Ekyp), was the craftsman behind the original “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign.

Photo by Matika Wilbur

Dr. Noe Noe Wong-Wilson

Kānaka Maoli

Hawai’i

Since 2009, the Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian people) have been actively opposing the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope. For them, Mauna Kea represents the most sacred site. The ongoing destruction and desecration caused by tourism and the presence of thirteen existing telescopes have severely harmed the mountain’s delicate and unique ecosystem and demonstrate a profound disregard for Kānaka cultural beliefs.

“Āina, or land, is a fundamental aspect of our identity as Hawaiians,” remarks Dr. Noe Noe Wong-Wilson, who is a professor, educator, cultural practitioner, and advocate for Native rights. “Witnessing its mistreatment like this is deeply painful to our spirit. It hurts our Native soul. That’s why we stand together.”

Photo by Matika Wilbur

John Sneezy

San Carlos Apache

California

For over thirty years, John Sneezy has graced the powwow arena as a Grass Dancer, showcasing a contemporary men’s dance style. In 2016, he traveled to the Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirit Powwow (BAAITS), where he felt empowered to dance as he had always desired: in the Traditional Cloth category, a beautiful slow dance traditionally performed by women.

He expresses, “I dance to honor those who took their own lives due to bullying. I dance for those who were murdered for being transgender, Two-Spirited, lesbian, or gay.

“When I come here to dance, I pour my heart into it, gathering their spirits and releasing them into the arena, because they couldn’t do it themselves... it symbolizes our unity as one.”

Photo by Matika Wilbur

Duwamish Land

Washington State

The Coast Salish Sea is the lifeblood of our Coast Salish communities. The dugout canoe was our means of traveling great distances, allowing us to secure ample food supplies, forge and renew Tribal alliances, and maintain social and ceremonial connections, which enabled our culture to not just survive but thrive.

Our lifestyle continued in this way until the arrival of colonizers.

Throughout the 1800s, the federal government sought to evict our people from our longhouses, forcing us into prisoner of war camps, now referred to as Reservations, and urging us to abandon our traditional ways of life.

Our ancestors escaped to the islands in their canoes, but the authorities responded by burning them or cutting them in half. Even now, you can visit the sites where our canoe remnants lie.

The canoe represents more than just a means of transport; it carries the dreams and resilience of our people. We are experiencing a cultural revival—the Coast Salish Sea calls us to connect with the ocean in our traditional practices. These spiritual journeys signify our strength and Indigenous sovereignty. This is a form of revolution.

Photo by Matika Wilbur

Michael Frank

Miccosukee

Florida

Michael Frank resides in a remarkable homeland—the expansive Everglades, often referred to as the “river of grass.” In its natural form, this area is teeming with biodiversity and is central to the Miccosukee identity and way of life. As a dedicated steward and advocate, Michael tirelessly works for the preservation of his people's land and culture.

"Our goal is to preserve our culture and traditional lifestyle," he emphasizes. "We maintain strict regulations about who can reside here, which helps safeguard our sovereignty."

This struggle traces back to the brutal anti-Indian military actions and the Indian Removal Act initiated under President Andrew Jackson, widely known as the Trail of Tears. Although the Miccosukee were forcibly displaced from the South, around one hundred individuals managed to stay, seeking refuge in traditional camps on islands within their territory, diligently maintaining their way of life.

Photo by Matika Wilbur

Ruth Demmert

Tlingit

Alaska

Ruth Demmert is an esteemed educator who has significantly impacted many lives through the development of Western curricula, as well as teaching Tlingit language, songs, dances, and proper drumming techniques. She states: “We continue to emphasize education while also integrating our culture, especially our core values. Respect for oneself. Respect for others. Respect for elders. Respect for the land and its gifts.

“Witnessing young children joyfully practicing what they’ve learned assures me that our culture will persist through them. I take pride in having contributed to this. Some mothers were pregnant with their babies while participating in the dance group, and now those children adore it. They cherish the drumming, which must feel akin to hearing their mother’s heartbeat.”

Project 562: Transforming Perspectives on Native America (Ten Speed Press) is now available. Discover more at project562.com.

Evaluation :

5/5