Shouting, swearing, and gourmet dining: The untold truths of the world’s most demanding restaurant scene

Hong Kong stands out as one of the toughest cities to run a restaurant – a fast-paced melting pot of shifting tastes, fierce competition, and challenging economics.

At the epicenter of its culinary scene, with ties to many of its most coveted spots, is publicist Geoffrey Wu.

Wu, along with his decade-old consultancy firm, The Forks and Spoons, partners with some of the city’s top restaurants and bars, including the Michelin two-star TATE Dining Room and Ando, one of the most exclusive reservations in town.

An unconventional publicist

“I wouldn’t claim we’re better than others, just that we’re different,” he shares with Dinogo Travel at The Baker and The Bottleman, a laid-back bakery and natural wine bar created by celebrity British chef Simon Rogan, where Wu opens up about the secrets of Hong Kong’s dining scene.

After being expelled from the University of Science and Technology in Hong Kong for skipping classes to play cards at McDonald's, Wu joined Amber, the renowned French restaurant led by Richard Ekkebus, as an operations staff member in 2005.

In the following years, Wu took on various marketing roles across industries, but his passion for food and beverage always pulled him back. In 2012, he founded his own consultancy firm in the F&B space.

Wu is far from a typical food and beverage publicist. He’s not known for being warm and friendly. Instead, he has a reputation for raising his voice at clients when they slip up or calling out journalists who haven’t done their homework.

“I’m not afraid to speak my mind – that’s a certainty. Sometimes, you need a consultant who’s blunt about what needs fixing. We’re not here to flatter your ego. Our job is to deliver results. We’re here to win,” Wu says, sounding more like a sports coach than a PR expert.

“If my goal was to please everyone, I’d be selling ice cream. Thankfully, most of my clients get that,” Wu adds.

One of these clients is Yenn Wong, the founder and CEO of JIA, the restaurant group behind beloved and award-winning spots in Hong Kong like Mono and Duddell’s.

“The Forks and Spoons understand the unique needs of each concept and always stay up to date with the latest strategies to ensure we get the most relevant publicity to our target audience, which ultimately drives positive revenue growth,” Wong tells Dinogo Travel.

‘The most cutthroat food and beverage market in the world’

According to Wu, one of the key responsibilities of an F&B publicist is to be physically present at the restaurant. He’s often found adjusting menus, trying new dishes, or simply catching up with clients.

It might involve anything from translating a restaurant’s à la carte menu from Chinese to English to collaborating with chefs on selecting dishes for a tasting menu, “so you can stay in the loop and show the team that you care,” Wu explains.

For example, later that day, he mentions he’s attending a trial lunch at Bluhouse, a new casual Italian eatery at the Rosewood Hotel in Kowloon.

“During a tasting, we evaluate everything – taste, presentation, and food temperature. We also assess the furniture, operational flow, pricing, and more,” he explains. “No new restaurant is ever flawless, but we aim to minimize the mistakes.”

“We’ve only worked with clients in Asia – Hong Kong, Macau, Maldives, and so on – but I genuinely believe that Hong Kong is the most ruthless food and beverage market in the world,” he asserts.

His statement isn’t unfounded.

Getting the launch right is crucial in Hong Kong, given the extreme competition.

Hong Kong is regularly ranked as the most expensive rental market in the world. The city’s residents are some of the biggest spenders on dining out, especially before the pandemic. Food imports are prohibitively costly.

This amount is nearly double what the average New York household spent on dining out during the same period.

“It’s such a densely packed market,” Wu notes.

“People are always talking. Hong Kong’s diners are also incredibly discerning. If you don’t get things right from the start, you’ll have to make significant changes. The real question is, will customers give you another shot? With so many options available, they’re likely to move on.”

“To build a thriving restaurant, it’s crucial to have a strong opening. Positive word of mouth will bring in the business. It’s that simple,” he adds.

A prime example: Bluhouse. It opened in June, and by the time of writing, dinner reservations are fully booked through October and November.

Chefs are playing a more significant role than ever before.

Hong Kong’s food and beverage industry has rapidly evolved over the past decade, partly due to the introduction of the Michelin Guide in 2009, as well as the rise of social media and a more active local food community.

Chefs in Hong Kong have seen their roles shift significantly.

“About 20 years ago, chefs primarily focused on cooking and serving food,” Wu recalls.

“In 2022, relationship-building has become essential. Chefs need to show up, interact with guests, take photos, and engage with the tables. The role of a chef has grown far beyond just cooking. It all comes down to the need for human connection. Customers, media, influencers, bloggers – everyone wants that personal connection,” Wu explains.

And it makes perfect business sense – guests are more likely to return to a restaurant where they’ve formed a personal bond with the chef.

The challenge, of course, is that not all chefs are naturally inclined to chat with diners. That’s where Wu’s expertise comes into play.

“We just keep encouraging them, again and again,” he says.

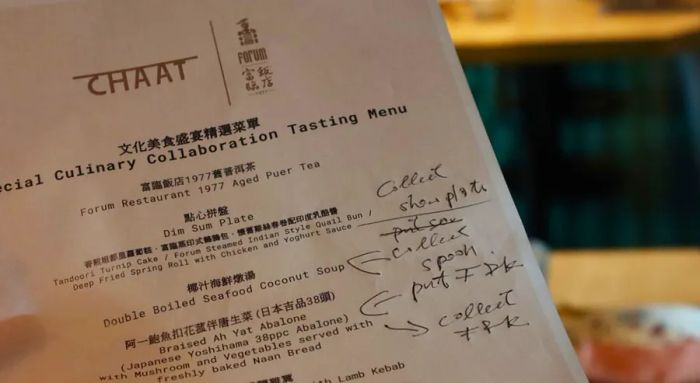

He points to Manav Tuli of Chaat, a modern Indian restaurant at the Rosewood, as a prime example. Chaat opened in 2020 and earned its first Michelin star just two years later.

Dishes like Tuli’s dramatic tandoori lobster – a blend of Indian flavors with a Hong Kong seafood twist – and a team of well-informed staff who expertly convey the stories behind each dish are just a few of the reasons Chaat is one of the hardest reservations to score in Hong Kong.

Reservations open two months ahead, and they’re snatched up within minutes.

But the true star of Chaat is Tuli himself, widely regarded as one of the city’s most adored culinary figures today.

“When he arrived two years ago, Tuli was unfamiliar with Hong Kong’s culinary scene and culture,” Wu recalls. “He’s a reserved person, but we share a common drive. For him, bringing his family to Hong Kong was about making a success of this opportunity. Since day one, we’ve been working closely to ensure that happens,” says Wu.

Wu urged Tuli to connect with guests and other chefs, attending events and meals as the chef began to establish his reputation.

Cold-calling doesn’t build a relationship.

On his days off, Wu organizes lunches for media professionals, including respected critics, and chefs he currently works with or may collaborate with in the future.

These lunches often take place at restaurants Wu isn’t directly affiliated with, ranging from Hop Sze, a humble Cantonese diner with a six-month wait list, to Forum Restaurant, a Chinese establishment boasting three Michelin stars.

“I worked until 4 a.m. this morning. I’m here because Geoffrey Wu arranged this lunch,” a food critic tells Dinogo Travel as he enters the private dining area at Forum.

The day’s menu features a variety of dishes – from street-food-style rice rolls to classic Cantonese sweet and sour pork, plus the restaurant’s renowned braised abalone.

As with most of Wu’s lunches, there’s also an off-menu surprise in store.

As the meal nears its end, Adam Wong, the executive chef, and CK Poon, the general manager, arrive with a pushcart.

“We’re considering adding this to the next menu update,” Poon says as he caramelizes sugar for the ba si apple, a Northern Chinese-style candied apple fritter. “This is the first time we’re trying this – so let us know your thoughts.”

The five-hour lunch concludes with industry gossip shared over bottles of cognac.

But Wu is always working.

He uses moments between conversations to suggest potential collaborations (Tuli and Wong discussed the possibility of a partnership between their restaurants), and fills any silence with jokes to keep the atmosphere lively.

“I always joke that I’m the chief entertainment officer,” Wu says. “Building relationships takes time. Cold calls and press releases don’t build genuine connections.”

Flavor is paramount, but it’s not the whole story.

At the end of the day, connections won’t take you far if the food doesn’t measure up or if the restaurant isn’t willing to adapt and grow.

“Flavor doesn’t deceive,” Wu says. “But everything – restaurants, bars, chefs – has an expiration date. You can’t stay on top forever. You need to continuously come up with fresh ideas to keep elevating the restaurant.”

This could mean introducing more tableside service, educating guests about the dishes, or even adding a pre-dessert bite to refresh the palate, he suggests.

One of Wu’s latest tasks involves refining the menu at his new client, Yong Fu, a Michelin-starred restaurant specializing in the high-end cuisine of Ningbo, a coastal city in eastern China.

He aims to streamline the original one-inch-thick menu and has introduced a tasting menu for a more curated dining experience.

Ningbo cuisine is frequently confused with Shanghai fare in Hong Kong. The tasting menu features dishes diners might not be familiar with, such as “sticky” boiled wax gourd and yellow croaker fish in sour broth, which showcase the three main flavors of Ningbo cuisine: savory, umami, and sticky.

Yu Qiong, the manager at Yong Fu, provides detailed explanations for each dish on the menu.

“These are the kinds of details that enhance the overall dining experience,” says Wu. He likens the marketing of restaurants to running: “Keep refining, keep pushing. My philosophy is simple – don’t stop until you cross the finish line.”

It’s a fitting analogy. The passionate runner rises at 5:45 a.m. most days to fit in his daily workout.

“I love the calm of Hong Kong’s early mornings, before the city fully wakes up. When you go for a run, you notice so much and find yourself thinking deeply,” says Wu.

So what was on his mind during that particular run?

“I was thinking about our interview. I was trying not to swear. I think I did pretty well – I only swore once,” he laughs.

Evaluation :

5/5