Sicily's One-Euro Homes: What Happened After?

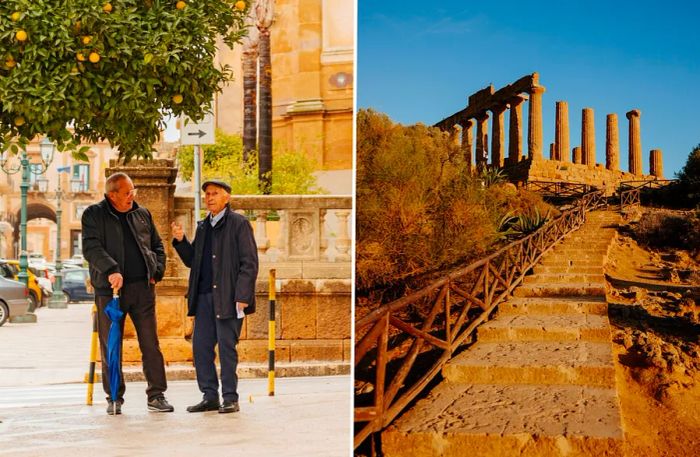

Like any unfamiliar small town, Sambuca di Sicilia, situated about an hour south of Palermo, can feel a bit daunting at first. Take a walk around its edge on a winter afternoon as the setting sun casts a warm glow on the buildings, and you'll notice the locals watching you. Try the town’s specialty minni di virgini—cream-filled, breast-shaped cakes with chocolate chips and squash jam—and a hush falls over the local bakery. This heightened awareness isn’t unfriendly; it simply makes you, as a visitor, feel somewhat conspicuous.

As I enter a quaint restaurant that evening in search of dinner, my feelings of self-consciousness peak. The only other diners, a middle-aged couple, fall silent as I approach my table. After a struggle with my order due to the waiter’s limited English and my even more limited Italian, I pull out a book to ease my discomfort while I wait. However, when the first dish arrives—a vibrant mound of ocher pasta adorned with bright shrimp and bits of pistachio—I can’t help but express my delight. This seems to shift the mood, and the waiter, now feeling like a friend, introduces himself as Giovanni. When two women with children come in, he seats them beside me and introduces them as well, saying, “La famiglia,” referring to his family and the chef, who pops out from the kitchen to greet me with a kiss for his wife.

Two hours later, stepping back into the cool night air, I feel uplifted by the warmth of the company and the robust Sicilian wine. Oh yes, I muse. I could make a life here.

I’m not the only one to have this thought. I came to Sicily to explore a program that has drawn countless people with the same dream. It offers a chance for those who may not have the means for a grand Tuscan villa complete with frescoes and a private vineyard to experience an alternate version of that dream. A program that provides a home for just one euro.

Photos by Julia Nimke

Since the 19th century, many villagers from Italy's poorer regions have relocated to wealthier areas and countries. This trend persists; in some locales, populations have dwindled so much that there aren't enough patients to sustain the local doctor or enough kids to fill the schools. Young people who left for education or work often choose not to return, leaving family homes empty for years. Around 2010, the village of Salemi in western Sicily pioneered a concept: what if these abandoned homes could be sold at an incredibly low price to attract new residents?

I wasn’t looking for a house, whether for one euro or more. My curiosity lay in whether this initiative was effective. Despite the warnings I'd heard about driving in Sicily—roads that abruptly turn into bumpy paths and drivers who seem to favor a close-quarters passing style—I opted to explore various villages participating in the program. Were these once-desolate towns revitalized by newcomers wanting to settle down? Were the new residents blending into the local culture, or was the influx of outsiders creating unexpected challenges? And did towns that welcomed new inhabitants risk losing the charm that originally drew them in?

Photos by Julia Nimke

The morning after my dinner in Sambuca di Sicilia, I set out to visit my first one-euro house. First, I stop at the Valley of the Temples. Nestled in a national park, this valley protects the remnants of a Greek colony established in the 6th century B.C.E. on land originally occupied by the indigenous Sicani. Centuries later, the original temples dedicated to Hercules and Hera still stand, alongside traces of Carthaginian destruction and Roman restoration. Over time, Vandals from the north and Muslims from Africa, as well as the French and Spanish, have also left their marks. As I gaze at the golden columns of the once-magnificent temples against the backdrop of the shimmering sea and blooming almond trees, I sense that history has a way of looping back on itself. It strikes me that outsiders have long been making their homes here.

Upon arriving in Cammarata, a steep, picturesque village with snow-dusted mountains, I immediately feel a sense of absence. The winter sun casts a beautiful light, yet the streets are eerily quiet. In the 15 minutes I stand in front of the rather drowsy town hall, where I’ve arranged to meet architect Martina Giracello, not a single person passes by.

Photo by Julia Nimke

At last, Giracello arrives with her lively corkscrew curls and sheds light on the local quietude. She explains, "Residents here sought larger, modern apartments," leading many to migrate to nearby San Giovanni Gemini, just half a mile away, where the landscape supports bigger buildings and improved amenities. Giracello notes that now, "the sole real estate agency in town doesn’t even deal with properties in the historic center,".

Similar to other young locals, Giracello and her partner, Gianluca, left for university and career opportunities. As they neared their 30s, they returned to Cammarata, craving a slower pace of life. Yet, they also desired a vibrant cultural scene and peers their age. "We looked at other towns with one-euro initiatives, but many buyers treat their homes as vacation spots, lacking a connection to the community," she shares. "We aimed for something different—building a community."

As we ascend Cammarata’s steep roads, the initial quiet transforms into the clamor of construction. 'Do you hear that?' Giracello inquires. 'It’s progress.'

They collaborated with other professionals to establish a volunteer group named StreetTo, which persuades owners of vacant properties to sell and assists foreigners in navigating inspections, paperwork, and renovations. In their mission to cultivate community, they also host exhibitions, concerts, and gatherings for both new and longtime residents. Motivated by their love for a revived Cammarata, StreetTo’s members provide these services at no charge. ("Currently, it’s aimed at foreigners, but we want to welcome Cammarata’s residents back, just as Gianluca and I have returned," Giracello states.)

However, it’s not solely selfless. The town benefits from this revitalization. As we navigate Cammarata’s steep paths, the quiet gives way to the noise of tools. "Do you hear that?" Giracello points out. "It’s progress."

Breathless from the ascent, we finally arrive at the first property, where Giracello reveals the stark reality of what one euro actually buys: not much at all. This structure resembles more of a short shed than a proper house, sporting what real estate listings might euphemistically describe as "significant structural issues"—or, more plainly, "a gaping hole in the roof."

If you desire something extravagant like a ceiling, Giracello informs me that you'll have to shell out a bit more. We continue to another house. As she pushes open the heavy wooden door, she shares its price—slightly over $10,000. The tall, narrow residence, characteristic of older Sicilian architecture, features a single room per floor, a stairwell littered with debris, and a kitchen that looks as if it hasn’t been updated since World War II, complete with a worn sink and outdated laminate countertops. However, the floor boasts stunning geometric tiles, and the windows offer a sweeping view of the valley. "We aim to find houses that aren't in great shape," Giracello explains. "The goal of the project is to help improve the town."

So far, StreetTo has facilitated the sale of 18 houses, but contract discussions and renovations are ongoing, meaning none of the buyers have moved in yet. Nonetheless, Giracello is optimistic that it won't be long before her village buzzes with new energy. She takes out her phone to share a video with me.

"When a German nurse and her husband purchased a property, a local couple was so thrilled to welcome newcomers that they threw a dinner for them and invited us too," she recounts. "Despite the language barrier—the Germans not speaking Italian and the Italians not speaking German—they’ve all become friends now." She pauses for emphasis. "We are all friends."

Photo by Julia Nimke

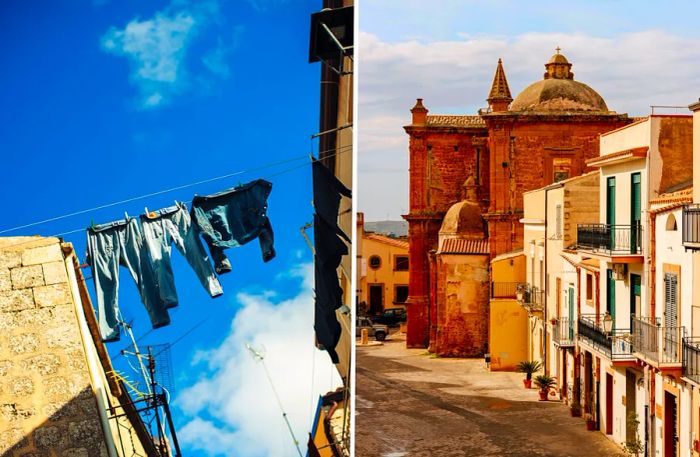

My next destination is Mussomeli, situated almost at the island's heart. Unlike many Sicilian towns that gracefully cling to ridges, Mussomeli is defined by its verticality. As I approach in the morning, jagged volcanic formations rising from the valley have ensnared pools of mist, giving the town an ethereal quality, as if it were floating among the clouds. It feels reminiscent of Middle Earth.

This enchanting illusion fades quickly: with a population nearing 11,000, Mussomeli boasts a Carrefour supermarket and even experiences a minor traffic jam. Yet, as I make my way to the town's center, the fantasy resurfaces. Mussomeli's core features ancient churches, quaint squares where children kick a ball, and stunning views from its winding streets overlooking that magical valley and a hill crowned by the ruins of a 14th-century castle.

The streets are so convoluted that I find myself lost and stop at a dimly lit bakery that sells nothing but focaccia. After purchasing a greasy square, I inquire with the elderly man at the counter about the influx of foreigners. "There aren’t many here now," he replies. "But in summer, they buy a lot of focaccia."

That seems like a fair exchange. While Mussomeli doesn't cater heavily to tourism, its charm and services have attracted over 200 affordable homes purchased by foreigners in recent years. Among them is Australian Danny McCubbin, who, after 17 years working for chef Jamie Oliver in London, was approached by producers in late 2019 for a show documenting one-euro adventures in Mussomeli. Although the pandemic halted the show, McCubbin discovered his purpose. By the end of 2020, he had committed to living permanently in Mussomeli, transforming his home into a community kitchen to assist those lacking adequate access to food.

Photos by Julia Nimke

After making a few wrong turns, I finally spot McCubbin, clearing dishes from a long communal table. He has just served lunch to local residents and Ukrainian children who have found refuge in the town after fleeing the war. These days, the Good Kitchen also provides weekly meals for the elderly and has taught some of Mussomeli’s youth how to cook. A group of older men frequent the space as their afternoon retreat, and there’s a free lunch every Sunday afternoon, with the only requirement being that those who can afford it bring something to share. Recently, Mussomeli’s mayor told McCubbin he had planted a seed, inspiring more locals to consider social projects. "My lifestyle has become so simple and joyful now," McCubbin reflects. "I can’t imagine where else I could have done this."

Rubia Andrade Daniels has also adapted her expectations. One of the first buyers in Mussomeli, she was drawn to a vibe reminiscent of the Brazil of her childhood, yet open to the diverse community she discovered in California, where she lived for the past 30 years. "In the first few days, I was puzzled by how kind everyone was to me," she chuckles. "Then I realized they treat everyone that way."

Andrade Daniels, who works in renewable energy, fell so in love with the town that she bought three one-euro homes during her initial visit in 2019. Four years later, her passion remains strong, but her timeline has adjusted: the kitchen in the house she plans to occupy part-time upon retirement wasn't completed until August 2023, and progress on the other two projects—an art gallery and a wellness center—has been delayed indefinitely, partly due to the pandemic. "You can’t hold American expectations here," she notes. "Things take as long as they need to."

Every day, I reflect on that pace when I return to my home base in Sambuca di Sicilia. Here, the demand for the available houses has been so high that one euro is no longer the final sale price; instead, it serves as the opening bid in an auction that can see prices escalate into the thousands. The campaign’s popularity prompted the municipality to launch a second round in 2021, with the starting price raised to two euros.

Margherita Licata, who has been spending her summers in Sambuca since childhood and made it her permanent home about 20 years ago, states that "99 percent" of the locals embrace the newcomers. What about the remaining 1 percent? "They’re concerned about being overrun by Americans," Licata shares, who works at a real estate agency in town. "If Sambuca eventually has a thousand outsiders, it will undeniably alter our lives. However, it may also mean that young people can find jobs here instead of leaving. If we desire that change, we must also be open to other transformations."

There’s a possibility that Sambuca might be reshaped by take-out coffee shops, big-box retailers, and other conveniences that appeal to the new residents. Some Americans have already voiced their frustrations about local teenagers riding their motorbikes through the streets at night. Additionally, social divides are starting to emerge: Among the more adventurous DIY buyers, rumors suggest that some wealthier newcomers wish to create an exclusive, members-only swimming pool.

Photos by Julia Nimke

Currently, there’s scant evidence of a non-Sicilian presence in Sambuca, making it hard to find anyone who speaks English. However, I did discover an archaeology museum where, after asking if it was open, a woman hurried out, flicked on the lights, and whisked me through the displayed antiquities at lightning speed, offering descriptions in Italian. I also stumbled upon a market near the traffic circle, where a fishmonger eagerly shared cooking tips for the sardines I purchased from his van. Plus, a café serving arancini finally made me appreciate the allure of fried rice balls, and the elderly man who initially glared at me while I enjoyed my breakfast cappuccino turned out to be simply waiting for a chance to ask if I knew his cousins in New Jersey.

Arriving in Sicily, I questioned whether the one-euro initiative would harm the towns that embraced it, replacing their rich traditions with consumerism and disrupting their relaxed lifestyle. When it became clear this wasn’t the case, I began to wonder if it was just a matter of time: perhaps the pandemic had merely slowed an already leisurely pace of business, and the inevitable changes would still come.

Yet, sitting once more in that same restaurant from my first night, it struck me that Sicily would thrive. Perhaps the slower rhythm wasn’t a flaw to be fixed but rather a quality that would keep Sicily charmingly and unmistakably itself. As I recalled the Valley of the Temples, I remembered that diverse peoples have been arriving on these shores for millennia. They may leave their marks and influence the culture, but a distinctly Sicilian spirit undeniably prevails.

Photos by Julia Nimke

Just before I left the island, I decided to visit Margherita Licata once more, this time for more personal reasons. Having seen enough one-euro homes to realize my imagination couldn’t bridge the gap of their dilapidated states, we headed straight for a "premium" property. As soon as she swung open the doors to the arched courtyard, I was captivated. The rooms, although worn down and adorned with old chandeliers and peeling wallpaper, were spacious and filled with light, featuring intact walls and beautiful patterned tile floors. Downstairs, there was an adjoining area ideal for a rental apartment, while upstairs, two rooftop terraces showcased views of the town center on one side and a serene lake on the other.

"Fifty thousand euros," Licata said with a playful wink. "But that’s merely the owner’s asking price."

While my bank account hadn’t magically increased during my time in Sicily, my imagination certainly had. In that moment, everything felt possible.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5