Syrian Refugees Are Revitalizing the Culinary Heritage of an Ancient Turkish City

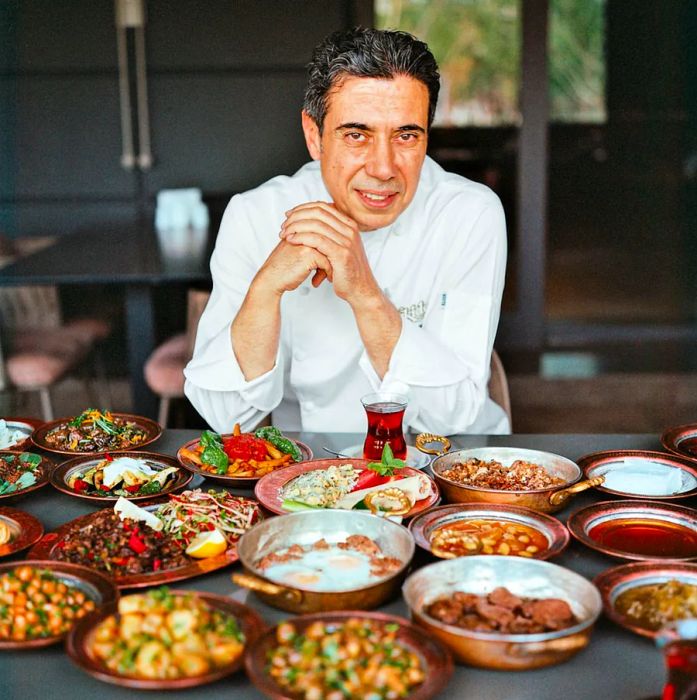

IT’S 11 A.M. IN GAZIANTEP, a city located in southeastern Türkiye, and I’m captivated by the vibrant display of our late breakfast. My partner, Barry, and I are dining at a restaurant named Orkide with our friend Filiz Hösükoğlu, a connoisseur of local culture and cuisine. Surrounding us, men in stylish leather jackets and women—some in shimmering black tops, others in flowing hijabs—savor menengiç, a warm beverage crafted from ground wild pistachios.

I circle our table in amazement, attempting to count and catalog all the dishes, but lose track after three dozen. There are fluffy mounds of kaymak (clotted buffalo cream) paired with honey from nearby hills; eggs scrambled with walnuts, fresh tarragon, and tiny roasted green olives; and eggs fried with topaç (beef confit). Copper bowls are filled with apricots stewed with fresh almonds and tahini in rich earthy tones. Every dish seems infused with mint, live fire, and sprinkles of local red pepper.

Photo by Rena Effendi

“This dish is my tribute to our region’s Sunday potluck breakfast tradition,” says Mustafa Özgugü̈ler, owner of Orkide, as a large platter of katmer is served. A delicate relative of the city’s famous baklava, katmer features layers of paper-thin pastry enveloping finely ground pistachios, baked to a perfect sugary crunch. “Katmer is like a cult, a drug . . .” Filiz whispers.

I had been longing to visit Gaziantep—Türkiye’s sixth-largest city, positioned just west of the Euphrates River and north of the Syrian border—ever since I first tasted its flavors two decades ago at Çiya, a renowned restaurant in Istanbul that specializes in southeastern Turkish cuisine. The dishes at Çiya were bold and inventive, bursting with fresh herbs, pomegranate molasses, and şalça (sun-dried tomato and pepper pastes). It felt worlds apart from the refined cooking of Istanbul, sparking a mild obsession with Gaziantep. Yet, for years, I hesitated to visit, always too preoccupied in Istanbul and perhaps worried that the reality wouldn’t meet my high expectations. Meanwhile, the excitement around the food only intensified, especially after UNESCO recognized Gaziantep as a Creative City of Gastronomy in 2015.

While I postponed my visit, the region's geopolitics continued to darken. In 2011, Syrian president Bashar al-Assad resorted to violence against pro-democracy protests, igniting a devastating civil war in Syria. Over the next decade, this conflict would force more than million refugees into Türkiye. The bustling city of Istanbul welcomed around 550,000, while Gaziantep took in at least 500,000, increasing its population by nearly a third—and earning its mayor, Fatma Şahin, international accolades for her effective policies prioritizing integration and tolerance.

For several years, I’ve been working on a new book exploring food and nationalism, and after completing the text, I felt it was finally time to make the trip. Like many food-loving pilgrims to Antep, as locals call Gaziantep, I was eager for kebabs made from grass-fed lamb, lahmacun (topped flatbreads) cooked in wood-fired ovens, and tiny bulgur dumplings swimming in yogurt soup. More somberly, I hoped to share a meal with Syrians who were carving out new lives. I wanted to understand how the recent arrivals—many from the war-torn city of Aleppo, 61 miles south—are transforming the food culture of this unique border region. From my research, I was already acquainted with Istanbul’s complex tapestry of Balkan Greek Armenian influences. Now, I sought to uncover the culinary evolution in Gaziantep—once a vital Silk Road trading post—marked by its intertwined and evolving cuisines, identities, and cultural narratives.

Photos by Rena Effendi

“OF COURSE, A HUNDRED YEARS AGO there was neither Türkiye nor Syria.” This insight comes from Cevdet and Murat Güllü, proprietors of Elmacı Pazarı Güllüoğlu, a renowned baklava shop in Antep’s historic bazaar, and our second stop on my first day in the city, guided by Filiz. In addition to their syrup-soaked pistachio treats, the brothers—whose great-grandfather established the shop—provide historical context. They explain that this area was once part of the Ottoman province of Haleb, with Aleppo at its heart for cuisine, culture, and commerce, while Antep served as a provincial subdistrict.

In the mid-19th century, the Güllüs’ great-grandfather, Çelebi, made a stop in Aleppo during his religious pilgrimage from Antep to Mecca. Captivated by the city’s baklava, he returned post-pilgrimage to master the craft before relocating back to Antep. In 1871, he founded the shop that still operates today. By the time the Ottoman Empire officially dissolved in 1922—over 70 years after the Güllüs’ great-grandfather trained in Aleppo—conflict and politics had reshaped borders, identities, and historical paths. Colonial powers divided the Levant (now Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) into British and French territories, while Mustafa Kemal Atatürk—“Father Turk”—established the modern republic of Türkiye. (The independent state of Syria did not emerge until 1944.)

We often instinctively attribute national identities to dishes, overlooking the fluidity of borders and the fact that many of the boundaries we consider fixed are actually recent and distorted. So, with my mouth full of baklava, I ask the brothers, “Can we truly label baklava as Turkish or Syrian?” Well . . . they respond. It’s complicated. After Türkiye’s establishment, Antep’s baklavaci (baklava makers) developed a unique style: they stretch the pastry so thin it’s nearly transparent, dust it with starch for added delicacy, and pour hot syrup over the freshly baked baklava. The result is markedly different from the original Aleppo version, which features thicker pastry and is drier and less sweet. Today, Filiz adds, Antep is celebrated as Türkiye’s baklava capital, producing 95 percent of the baklava sold across the nation.

Photo by Rena Effendi

After parting with the brothers, Filiz guides us through the bustling Coppersmith Bazaar’s arching lanes, filled with the rhythmic sounds of artisans crafting their goods. I feel fortunate to have her as our guide. A walking encyclopedia of local culinary customs, she also has extensive experience in NGOs, focusing on integrating migrants through programs like vocational training. That evening, to gain insight into the Syrian culinary and cultural viewpoint, she organizes a dinner with her friend Yakzan Shishakly. We’re set to meet at Hışvahan, a restaurant housed in a 16th-century caravansary that has been transformed into a stylish boutique hotel. Upon arrival, we find Yakzan already at a candlelit table, enjoying a raki, Türkiye’s anise-flavored spirit. “The food here is exceptional,” he remarks. “Plus, it’s one of the few spots in town serving drinks.” He seems to be in need of one.

In his early forties, Yakzan presents as a compassionate bon vivant who has taken on a daunting, tragic mission. A grandson of Adib Shishakli, one of Syria’s early presidents who was assassinated in 1964, he spent his childhood in Damascus. In 1999, he moved to Houston, gained U.S. citizenship, and ran a thriving air-conditioning business. Then, in 2011, “Syria happened,” as he succinctly puts it.

Heartbroken and eager to help, Yakzan quickly returned to Syria, where he saw hundreds of internally displaced persons (IDPs) living in makeshift tents under olive trees. He began raising funds to establish a camp just north of Idlib, 41 miles from Aleppo. By mid-2012, Yakzan’s Olive Tree became the first major displaced persons camp in Syria, turning into a sprawling tent city housing over 20,000 IDPs. (Today, more than 180,000 IDPs reside in the camp.) Currently, his NGO, the Maram Foundation, oversees five camps and provides logistical support to over a dozen others. Although he can no longer travel freely in Syria due to risks of kidnapping or assassination, Yakzan continues to manage countless crises from his office in Antep—amidst the despair of a seemingly endless war and a generation of children in camps without schools. How does he cope? With a resigned smile, he replies, “I listen to motivational speeches first thing each morning.”

However, Yakzan is keen to avoid portraying Syrians merely as victims reliant on NGO aid. This, he believes, strips them of their dignity. The truth outside the camps reflects a normal life, especially in cities like Antep, which has welcomed a significant portion of Aleppo’s middle class. Yet, he adds, the trauma remains just beneath the surface: unexpected tears or disputes with taxi drivers.

“Does it bring you comfort that the culture and cuisine share so many similarities?” I inquire, suddenly recalling the intense alienation I felt tasting American foods back in the 1970s, shortly after my mother and I arrived in the United States as refugees from the USSR.

“Absolutely, it eases the culture shock,” Yakzan replies as a waiter serves up spicy dips and stuffed vegetables. “We have our mutual love for pomegranates, hot peppers, and olives, plus our obsession with pistachios.” A passionate cook himself (“It helps alleviate stress”), Yakzan takes a thoughtful bite of eggplant-and-tomato dolmas. “[These dolmas] share the same idea as ours, just with different spices,” he notes. The same goes for the içli köfte, fried bulgur shells filled with meat and onions—known as kibbeh to Syrians—of which Aleppo boasts many more varieties. “However,” he stresses, “Syrian cuisine can vary greatly from Damascus to Homs to Aleppo.”

I remember Armenian writer Takuhi Tovmasyan’s words: “Cuisines don’t have nationalities, only geographies.” So, I ask what’s been on my mind: Are Syrians here influencing the local food and restaurant scene? “Ah, journalists,” Yakzan chuckles, “always hunting for catchy headlines!”

Yakzan asserts that integration is occurring. The city has built homes for refugees within existing neighborhoods rather than isolating them in camps on the outskirts. It has also ensured that local resources, including community centers offering cooking and dance classes in both Turkish and Arabic, are accessible to everyone. However, he acknowledges that integration can be subtle and gradual—even in this city hailed as a model of tolerance.

“In any society, foreigners can be seen as a threat,” he continues. Locals were curious about Syrian flatbread, yet hesitant to embrace it; they would purchase it discreetly at night. “But now it’s woven into the culture, alongside countless small exchanges,” Yakzan explains. “A Syrian chef might use local mint in a dish instead of Aleppo’s cilantro. A Syrian restaurant features a Turkish dish on its menu. A Turk buys our seven-spice blend from a Syrian grocer.”

Photo by Rena Effendi

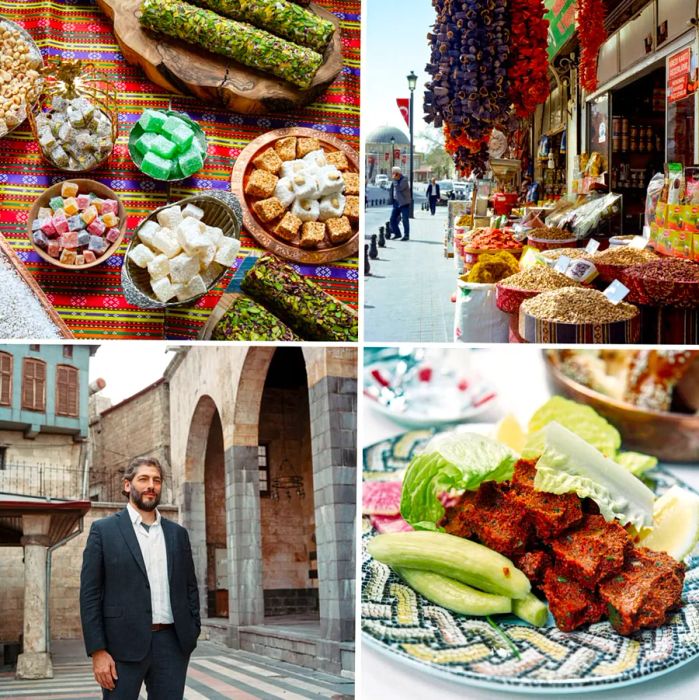

THE NEXT MORNING, I reflect on Yakzan’s thoughts about cultural blending while tasting lokum (Turkish delight). I meet Emel Shamma, a confectioner and entrepreneur, in the bright lights of Antep’s Women Entrepreneur Support Center. Originally from Aleppo, she moved to Antep in 2017 after spending four months in a refugee camp, where she witnessed the horrors of phosphorus bombs falling from planes. At that time, she was a struggling single mother with little more than a few gold bracelets. After seeing an ad for vocational training from the local Chamber of Industry, she began her apprenticeship at a lokum factory. With the help of a U.N. grant, she launched her own business two years ago and is now celebrated as a symbol of Syrian female empowerment in Gaziantep, producing a full ton of lokum daily and exporting it to various countries across Europe and beyond.

While we often associate lokum—with its roots in the Arabic rahat-ul-hulkum—solely with Türkiye, these jewel-like sweets were integral to life in Aleppo as well, given as gifts to commemorate the birth of a child or the return of a pilgrim from hajj. Finding traditional Turkish lokum flavors somewhat unfamiliar, Emel started creating her own, blending unique spice mixes with mastic (a pine resin), muscat, and cardamom. She invested in fragrant dried Isparta roses and ensured the pistachios were freshly cracked to maintain their flavor intensity, a technique she learned from her family, who owned pistachio orchards in Aleppo.

“I see lokum as an amber,” she explains, “melding the flavors of my homeland with those of my new home.” As I taste a red, pomegranate-flavored “amber” featuring emerald pistachios—unlike any lokum I’ve encountered in Türkiye—I realize this is the kind of cultural “fusion” Yakzan mentioned. It may not make for an eye-catching headline, but it’s a small, nuanced detail—one that could gradually contribute to a transformed food identity for the city. Emel nods in agreement. “Antep and Aleppo are like twins raised in different lands,” she reflects. “Separated by war yet reunited once more.”

As I stroll through the city later that day, the essence of Aleppo seems to linger everywhere, waiting to be discovered.

It's found in the Ottoman mosques and hammams made of striped stone, commissioned by Aleppo's governors in the 16th century. The echoes are present in the hilltop citadel—a smaller counterpart of the one still standing in Syria—and in the lustrous cotton-and-silk kutnu fabric, an important craft from Aleppo that, like baklava, has carved out its own identity in the Turkish Republic.

Photo by Rena Effendi

WITH AN APPETITE for Aleppian cuisine in Gaziantep, I feel a surge of excitement when Filiz sets up a lunch for us the next day at Lazord. This cherished Syrian spot is nestled among a row of modest businesses adorned with bright signage in both Arabic and Turkish. Joining us are Rami Sharrack, a consultant focused on entrepreneurial initiatives for refugees, and Shukran, a social activist who escaped Aleppo in 2013.

As we enjoy the delightful combination of Syrian bread dipped into exquisite hummus and mtebbel, a rich blend of eggplant and yogurt—"looser, tangier, with more olive oil than Turkish dips," Filiz points out—Shukran, a warm-hearted mother of nine whose children are spread across the globe, shares her story. Shortly after arriving in Antep, she initiated a social project aimed at assisting Syrian war widows through culinary arts. With an initial investment of $1,000, she transformed a derelict house into a safe haven that accommodates 50 women at once. "It’s a secure space and a source of income for them," she explains. This initiative also offers a taste of home to members of the diaspora through dishes like makdous (pickled stuffed eggplants) and shish barak, meat-filled dumplings served in garlic-yogurt sauce. When I inquire about her longings, she shrugs and replies, "Here, the region is the same and the dishes are similar. Maybe I miss the wild summer herbs from our hills? Or the stew made from the leafy plant we call molokhia?"

Rami adds, "Syrian farmers have begun cultivating molokhia in Türkiye and now export it to various countries with significant Syrian populations. Additionally, Syrians here sell about 200,000 bags of khubz [bread] every morning," he notes. "These are all small yet significant success stories!"

Photo by Rena Effendi

While we converse, Lobna Helli, the owner of Lazord, busily organizes with her teenage daughter and mother, preparing to deliver 100 meals to the less fortunate, both Turkish and Syrian, a routine they uphold every Friday. Once an HR manager in Aleppo, Lobna escaped to Antep in 2015 after her husband was detained and tortured by the Assad regime. A small family loan allowed her to start a modest café. Following the COVID pandemic, she expanded her efforts by establishing a charity kitchen called Humanity Gathers Us. Like Shukran, she aimed to unite Syrian women who prepare food from their homes. Now, she aids them in marketing and selling their dishes while also providing and distributing grocery cards for those in need.

Seated at a table adorned with her grandmother’s lace tablecloth—a cherished reminder of her Aleppo roots—Lobna takes a moment to catch her breath before joining us to enjoy her mother’s freshly baked fatayer, pies overflowing with spinach. Alongside them are mumbar, the beloved dish that stirs homesickness in all Syrians, filled with a savory mix of rice, chickpeas, meat, and her unique blend of spices, packed with black pepper. Shukran beams with delight at the yalanji, grape leaves stuffed with a rice mixture that pulsates with red pepper and pomegranate. When asked what gives this dish its special Aleppian flair compared to the Turkish version, Shukran leans in and whispers, "Ground coffee." With confidence, she states that 60 percent of the dishes from Antep and Aleppo are alike, but insists, "Our Aleppo cuisine is more diverse, adaptable, and expansive," as Filiz nods in agreement and adds, "But only Antep has [the pastry] katmer!"

Before long, our plates are empty, and our bellies are satisfied. Time seems to fade as I sip on the sweet, syrupy Turkish (or Arabic? Levantine?) coffee with these remarkable women—true pillars of the community—who delight in discussing the nuances of recipes and cultural identities. In moments like this, it’s difficult to resist the age-old notion of food as a source of existential comfort that unites us. Meanwhile, a few hundred miles away, across a border that emerged in the 20th century and remained fluid until a devastating war uprooted these individuals from their homes, the conflict continues unabated.

Evaluation :

5/5