Texas, You Have My Heart

Now living in Los Angeles, I often catch people off guard when I mention I'm from Texas—many presume I’m a Californian. The idea of being an “Asian American” from the South doesn’t quite fit their expectations. I can’t really blame them; I struggled with my own sense of belonging in Texas for a long time.

My father is a white American, while my mother is benshengren Taiwanese, referring to families that have resided in Taiwan for centuries before the Chinese Nationalists came from the mainland in 1949. I like to think of myself as a living, breathing ambiguous image—like those drawings that can be interpreted as either a duck or a bunny. White individuals often see me as Asian, while Asian individuals tend to perceive me as white, or at least intriguingly ambiguous in ethnicity.

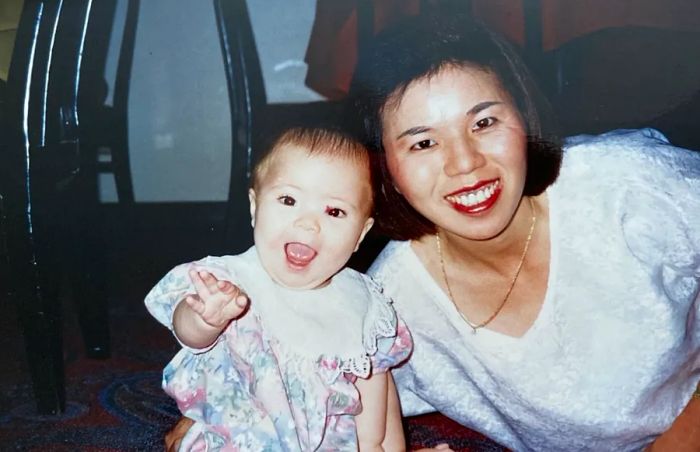

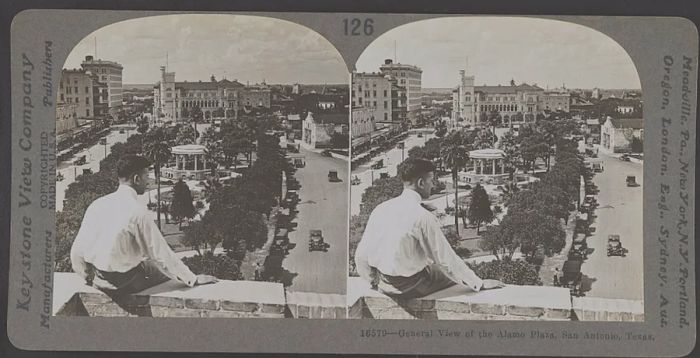

I was born and raised in San Antonio, roughly an hour’s drive from Austin. Best known for the Alamo, San Antonio is a military town, with several bases nearby, such as Fort Sam Houston, Camp Bullis, and Lackland Air Force Base, where Johnny Cash completed his basic training during a brief military career. It’s a quiet town, where my parents first crossed paths in the 1980s at my aunt’s Chinese restaurant, where my mom worked as a waitress for over 30 years.

Image courtesy of Mae Hamilton

My dad was born in Madison, Wisconsin, but he spent his formative years in the piney woods of a small town in East Texas. There, he would roam the thick underbrush with a coon dog, smoke grapevines, and engage in the daring act of “riding the pines”—climbing to the top of a thin tree, pulling its crown down with his weight, and leaping off just before it snapped back up. His family moved to San Antonio during his teenage years. He often spent afternoons experimenting with acid at the airport, watching planes depart for destinations he had yet to explore. In his 20s, he hitchhiked across the country for a year but ultimately returned to the place he had always considered home: Texas.

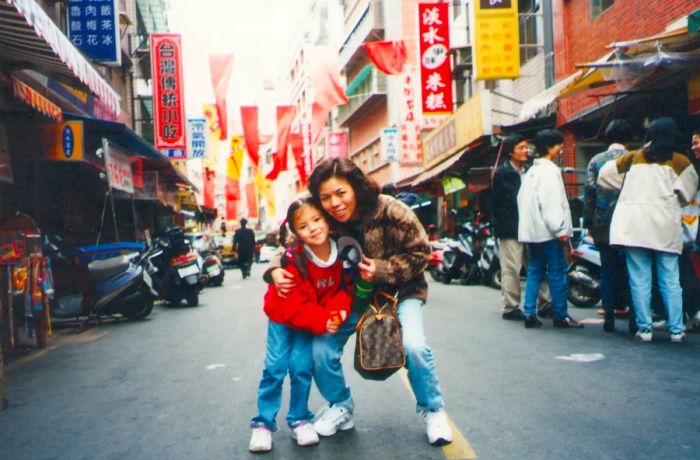

Image courtesy of Mae Hamilton

My mother’s childhood was vastly different. As the third youngest of eight siblings, she grew up in a shantytown in Taipei, close to the Tamsui River, where the family of ten lived in a cramped two-story shack smaller than a typical American bedroom. Once, a police officer demanded a bribe to ignore their illegally constructed home, and when her eldest sister refused, he demolished their house with a single kick. Ultimately, it was taken by the government and bulldozed. The site of their former home has since transformed into a bustling boulevard.

My father has always been certain of his place in Texas, while my mother continues to struggle to carve out her own space in the state, a task that feels endless and uphill. When I was young, she took night classes at the local middle school to improve her English. Now, she practices with an online program. However, she still hesitates to speak with strangers on the phone, fearing they won't understand her. She avoids driving on the interstate, worried she won’t be able to read the signs fast enough as they zip by at 75 miles per hour. When she needs to see a new doctor, she often asks me or my dad to accompany her to help with the intake forms. Growing up with two parents from such different backgrounds left me feeling somewhat adrift, caught between two cultures, never fully belonging to either.

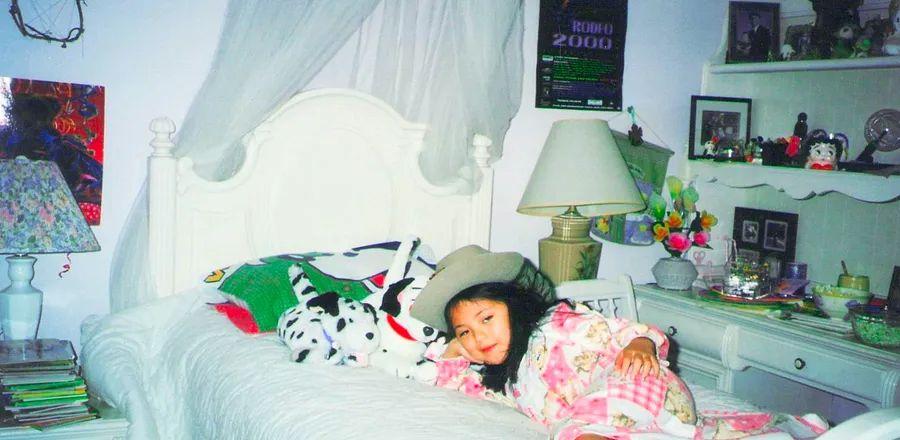

Image courtesy of Mae Hamilton

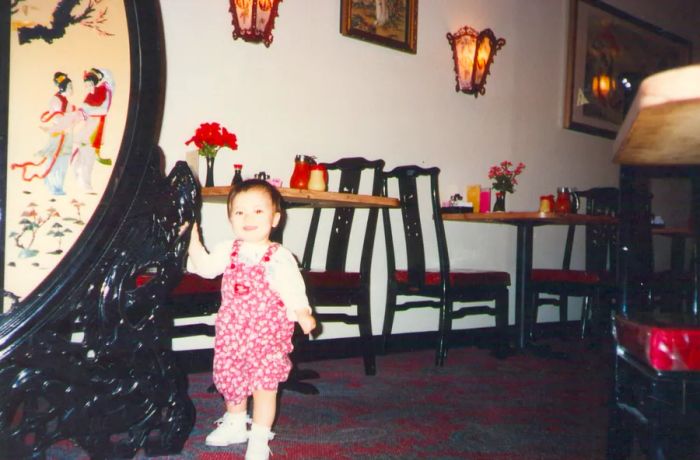

As a child, my world revolved around my aunt’s restaurant, one of the few places serving Chinese cuisine in town. When I was a toddler, I would dash between tables laden with egg rolls, broccoli beef, and General Tso’s chicken, stumbling over an apron that was still too big for me. While my Taiwanese uncle managed the place, one of his sous chefs was a Mexican man nicknamed Pato (Spanish for duck) because of his waddling gait—he wore Guns N’ Roses and Korn T-shirts daily. The prep cook was a tall, wiry Vietnamese man, and the dishwasher was an older Indigenous Mexican woman who spoke her native language and a bit of Spanish, often crocheting during her breaks.

I had a close bond with the waitresses. Suk, Penny, and Grace were all Korean women who came to America after marrying (and later divorcing) servicemen. They took care of me on their days off while my mom worked, cooking me Korean dishes like doenjang jjigae, gamjatang, and banchan. Another waitress, Wendy, had fled civil war and gang violence in El Salvador and had three children who became my childhood friends. My idol, however, was Sandy, a woman in her 20s who I thought was the most beautiful person in the world. She rolled her r’s even when speaking English, brought me De la Rosa Mazapán from Mexico, added a Marilyn Monroe-style beauty mark to her cheek, and wore her honey brown hair in a bun. I would always beg her to help me style my hair the same way.

Image credit: Mae Hamilton

“You know,” she remarked, popping her gum as she helped me style my hair into a ponytail, “I have a feeling you'll end up marrying an older man one day.”

There’s a saying that it takes a village to raise a child, and the staff at the restaurant formed my vibrant, diverse village—a mix of individuals from around the world who came to Texas in pursuit of better opportunities. This was my sense of community before I truly grasped what community meant. Inside my aunt’s restaurant, people of various backgrounds, origins, and beliefs collaborated seamlessly to serve hot dishes like moo shu pork, vegetarian tofu, and Peking duck to customers. However, the world outside those vivid scarlet doors was a different narrative altogether.

All Mixed Up

In my childhood, San Antonio wasn't particularly known for its Asian community. According to 2000 census data, when I was six, around 65% of the population was Latino, 24% was white, and 7% was Black, with only about 3% identifying as Asian or Pacific Islander. Growing up on the Latino westside, I attended Alamo Heights, a wealthy neighborhood often referred to as “Alamo whites,” even though I didn't reside in that district.

Image credit: Library of Congress

As a child, it felt like every woman around me sported big blonde hair, while their husbands had various numerical suffixes to their last names. I yearned to blend in with my classmates, but I was the only Asian student in my class who wasn't adopted. Most importantly, I was much poorer than my peers and lacked even a single Juicy Couture tracksuit. Once, when I wore cowboy boots to school, a boy curled his lip and mocked, “Asians and cowboy boots don’t mix.”

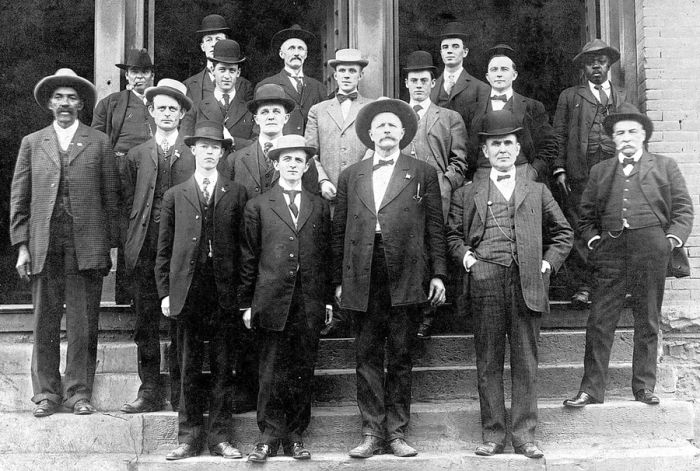

Outside of school, I also struggled to see myself in the broader narrative of Texas, a feeling that persisted into my young adulthood. However, in 2015, when I was about 20, I came across a local newspaper article titled “S.A. Once Home to State’s No. 1 Chinese Community.” It detailed how in 1917, General John J. Pershing brought over 500 Chinese refugees from Mexico to San Antonio. These individuals had assisted the U.S. Army during their (unsuccessful) pursuit of Pancho Villa and feared persecution if they remained in Mexico, and with good reason; only a few years prior, 303 Chinese individuals were murdered in Torreón, Coahuila, in a horrific racially motivated attack.

Image credit: Library of Congress

Upon their arrival in the U.S., the group known as the “Pershing Chinese” settled near Fort Sam Houston, working as laborers, cooks, waiters, and laundry workers. More than half of them remained in the area, many marrying local Mexican women. They established families, opened businesses, and founded San Antonio’s first Chinese school, the San Saba Chinese School.

Today, Houston is recognized as the Chinese epicenter of the state, but prior to the surge in Asian immigration during the 1980s, that distinction belonged to San Antonio. This history served as a reminder that families like mine had roots in this place long before our arrival, offering a small spark of hope that I was exactly where I belonged.

Image credit: Library of Congress

At 21, I felt it was the right moment to spend some time in Taiwan. I took an internship in Tainan and enjoyed a summer there while studying at the University of Texas at Austin. This wasn’t my first visit to Taiwan; my family traveled there almost every year, and I had spent a month the previous summer teaching English in Hsinchu. However, this would be the longest I’d stayed on the island and away from home.

That summer, I experienced an unparalleled sense of welcome and belonging. The auntie from whom I purchased fan tuan (a breakfast treat made of glutinous rice filled with pickled radish, pork floss, and a Chinese cruller) and sweet doujiang (soy milk) greeted me by name each morning and even tried to introduce me to her nephew. I relished being able to order duck necks, tongues, and other offal at the lu wei takeout without feeling shy or apologetic—dishes that weren’t even on the menu back home. When I met my coworkers at the night market after work, they would urge me to stay in Taiwan, and I truly wanted to.

Image credit: Mae Hamilton

However, it was clear that I would never truly fit in in Taiwan either. One time, while having lunch with a friend in the quaint northern town of Jiufen, the waitress cheerfully remarked, “Your Chinese is very impressive for a Japanese person!” When strangers engaged me in conversation, they often asked, “Where are you from?” It wasn’t meant to be hurtful, but the implication was unmistakable—I don’t see people who look like you around here very often.

During those tumultuous college years on the brink of adulthood, my life felt like a poorly written Dr. Seuss book: I don’t fit in here, I don’t fit in there, I don’t fit in anywhere! I had spent years relearning Mandarin and immersing myself in Taiwanese culture, believing I could find a sense of home halfway around the world in the South China Sea. But one evening, as I sat alone on my dorm bed in Tainan, listening to the typhoon howl and slam palm leaves against my window, I wondered, “What if I just stopped trying so hard to fit in all the time? What if I just was?”

I found solace in an unexpected genre: outlaw country music. I can groove to Brooks and Dunn’s “Boot Scootin’ Boogie” and George Strait’s “Adalida” like any proud Texan, but when I talk about outlaw country, I mean the raw, gritty songs that tug at your heart while you sip a beer and wipe away a tear. These are the tracks you drop a quarter for in the jukebox when you’re the last patron at a dimly lit bar. Artists like Guy Clark, Terry Allen, Doug Sahm, and Townes Van Zandt, who embraced their long hair, poetry, and creative spirit, knew they didn’t fit into Texas’ rigid social norms—and frankly, they didn’t care. They were the outcasts and wanderers who lived boldly on the fringes of Texas society, especially Townes, who wrote poignant ballads about Mexican bandits, lost souls, and hopeless junkies.

I had long appreciated folk and country music, spurred by a high school obsession with Bob Dylan, but this felt different. Listening to these artists, who still deeply cherished their roots—even if they didn’t quite belong—instilled a sense of connection in me. The truth is, Texas has always been a refuge for kooks, oddballs, musicians, dreamers, and artists, just as much as it has been for cowboys, football heroes, and megachurch leaders. The message was straightforward, yet I grasped it fully: It’s perfectly fine to be different. In fact, it takes a bit of courage to embrace that uniqueness.

After returning from Taiwan, I embarked on a road trip and observed that in every tiny Texas town, regardless of its size, there always seemed to be at least one Chinese restaurant. How many others in the world shared my feelings? People who weren’t merely historical footnotes but were alive and present in this moment, just like me?

It felt reminiscent of that moment in The Wizard of Oz when the gloomy sepia tones explode into vibrant Technicolor as Dorothy discovers the yellow brick road. I couldn’t be the only one who had grown up in this strange space between two cultures—there were likely others in these small towns who believed they were the only Asian kids in the entire state during their childhood. I was nearly in tears when I shared this with my mother, and she simply shrugged and said, “We are everywhere.”

That was such an outlaw country thing for her to say.

California Sun

I met my husband—the older man Sandy had foretold about—during my final year of college. After less than a year of getting to know each other, but deeply in love, we decided to move to Los Angeles together.

Image credit: Library of Congress

Over the past five years living in California, I’ve sensed a distinct attitude toward Texas—a feeling of unfamiliarity and otherness. There are undercurrents of suspicion and fear. Topics like Texas’s strict abortion trigger laws, the rights of trans individuals, humanitarian migrant crises, and the tragedy at Uvalde dominate the narratives about Texas. I wrestled with my identity in Taiwan, but moving to a new state offered me a fresh perspective on Texas. My homesickness drove me to immerse myself in literature about Texas and incorporate it into my writing. My home state is undoubtedly messy and complex, yet it can also be profoundly beautiful.

For starters, Texas is the second most diverse state in the nation, right behind California. Immigrants make up roughly 17 percent of Texas's population. Recent census data shows that the Latino population has surpassed that of white, non-Latino Texans, accounting for 40 percent compared to 39 percent. According to a report by the Texas Tribune in August 2021, Texas gained the highest number of residents of any state since the last census in 2010, with over 95 percent of that growth attributed to Latino, Black, and Asian populations, all of which outpaced white residents. Asian Texans, though they represent just 5.5 percent of the state, grew the fastest, adding 613,092 individuals since 2010. Houston has gained national attention for being the most diverse city in the United States, as highlighted by publications like the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times.

Yet, even prior to modern immigration waves, Texas was already a vibrant tapestry. Before it became Texas, it was part of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas, and the state is rich with Tejano families who have called this land home for centuries, long before current borders were established. Black Texans have also made invaluable contributions to both state and national culture. The iconic cattle drives of the late 1800s, which helped enrich the state, were predominantly manned by Black and Mexican rancheros (one in four cowboys was Black), and Bass Reeves, the legendary deputy U.S. marshal who inspired the Lone Ranger story, was Black. At the Alamo, individuals of both Black and Mexican descent famously defended the San Antonio mission alongside Davy Crockett and James Bowie.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Yet, explaining all of this concisely in response to a raised eyebrow and the remark, “From Texas, huh?” is quite a challenge. How do you articulate the complexities of loving a place that may not fully reciprocate that love? How do you reconcile your emotions with Texas’s troubling history of lynchings, hate crimes, and xenophobic policies that the state government has adopted against people of color?

The image I hold of Texas is one that is vibrant and diverse. It’s a dreamlike realm filled with outlaw country musicians, resonances of a history that refuses to be forgotten, and a future brimming with hope and potential, as the state grows more diverse with each new wave of immigrants. It’s a vision I worry isn’t mirrored in the legislature.

However, I often reflect on how, when something pushes you away, the best response is to wrap your arms around it tighter and embrace it, perhaps out of love and a touch of defiance. Maybe even pen a song or two about it in a saloon at night—or write an essay, for that matter.

Evaluation :

5/5