The process of building an airplane engine

At Rolls-Royce Aerospace's UK facility, machinery hums, fans buzz, and blades screech as over 1,000 employees work meticulously to create the powerhouses that drive airplanes into the sky.

Michael McCree, a lead engineer at Rolls-Royce's Trent XWB line, explains, 'It's all about meeting customer demands and matching the growing popularity of the engines we're crafting.'

'We’ve engineered popular designs and successful products, but the real challenge is maintaining a steady production pace,' he adds.

The Trent XWB is a turbofan engine designed for the Airbus A350 XWB. If you’ve flown on Qatar Airways, Singapore Airlines, or Lufthansa, there’s a good chance one of these engines was powering your plane.

Over 1,800 Trent XWB engines are either in service or on order globally. At Rolls-Royce's Derby facility in the East Midlands of England, the focus is on manufacturing these engines with speed, precision, and the highest quality standards.

McCree takes Dinogo Travel behind the scenes, showing the step-by-step journey of how the XWB engine is built, from its creation and rigorous testing to the moment it soars through the sky.

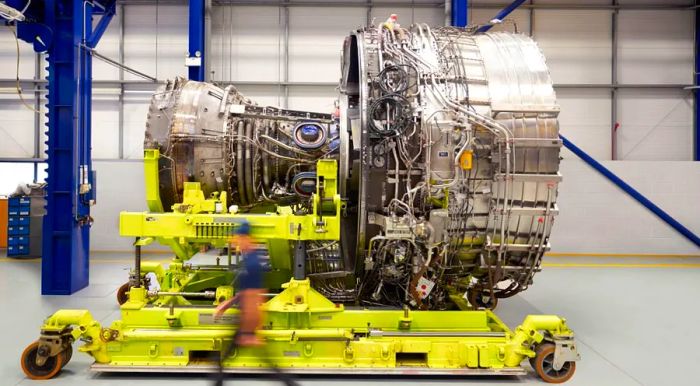

A true engineering masterpiece

The Trent XWB engine consists of eight essential modules.

'We manufacture six of those eight modules right here in Derby,' McCree explains. 'The remaining two are outsourced to our suppliers.'

The IP compressor is produced by KHI in Japan, while the LP turbine is assembled by ITP in Spain before being shipped back to the UK.

McCree begins the tour of the Derby production line with the fan case.

The fan case encircles the engine and is typically covered by cowling, displaying both the product's name and the airline's logo.

'It's designed to house all the wiring and pipework, as well as secure the fan blades,' McCree explains, pointing to an unassembled fan case with a carbon fiber top.

The fan case is divided into a 'wet' side and a 'dry' side. The wet side contains the fuel and oil, while the dry side houses the cables and electronics, kept safely away from the liquids to avoid any potential issues.

'We have three fitters working each shift on every fan case,' McCree says.

'Each fan case is divided into thirds, so each fitter works in their designated area, avoiding any overlap or the need to move around each other,' McCree adds.

Next comes the part of the engine visible on an aircraft – the large fan spinning at the front.

Weights are added to the fan to ensure it is properly balanced and functions within its specifications.

'Similar to balancing car wheels, we attach additional weights inside the fan to correct any slight vibrations. Our goal is to achieve a net zero vibration across the entire engine, ensuring the smoothest possible ride for passengers,' McCree explains.

At Rolls-Royce, passenger experience is always top priority. Ideally, you should hardly notice the engine – except for the fact that it’s effortlessly taking you to your destination.

As Dinogo Travel observes this stage of the production line, one Rolls-Royce technician spins the fan inside a large machine. Software assists him in determining the precise locations to add the weights.

'Achieving perfect balance and precision is absolutely crucial,' McCree says.

Any imbalance could lead to serious issues with the engine's performance.

The next steps in the process

As you walk through the facility, it's bustling with activity. While machines are present, the process is far from as automated as one might expect.

'It's a highly specialized role – not just a job for big machines,' says McCree, who earned his Mechanical Engineering degree at Imperial College London before joining Rolls-Royce as a graduate engineer.

The next step involves connecting the combustor section to the intercase. The intercase is where the engine links to the gearbox, with the central shaft running through it.

This part of the assembly process occurs on a skillet line:

'The floor moves forward while the tooling stays in place, allowing the team to follow the engine as it advances,' McCree explains.

At this stage, the engine is essentially 'naked,' says McCree. It's time to transform the core into what's known as a 'dress core.'

McCree explains, "When you assemble the core, you attach all the pipes that connect the hot and cold sections of the engine, as well as any cables running through it."

Next, the fan casing is placed on the floor, and the engine is lifted and positioned in the middle of the casing.

At this point, the engine resembles an airplane engine, though it still isn't ready for flight.

The testing phase.

One of the most impressive features of the facility is the test bed.

It’s a massive, expansive room featuring a colossal facility designed to securely hold the engine, primed for testing.

While the engine rests on the test bed, testers assess how the engine handles startups, emergency shutdowns, and encounters with birds—both real and simulated with gelatin models thrown into the engine to mimic a bird strike.

Thrust measurements are also taken, as any imbalance could affect the engine’s performance.

The engine undergoes a test for potential cabin odor issues, often referred to as a sniff test.

McCree explains, "We ensure there’s no odor emanating from the engine that could make its way into the cabin."

What steps are taken if there's a suspicion of an oil leak?

Cameras are inserted into the engine, allowing for adjustments to be made as needed.

The duration of testing at Rolls-Royce can vary. New models undergo extensive testing for several days, while engines already in production can be confirmed as flight-ready after a shorter testing period.

Lifting the airplane off the ground.

Once the engine is prepared for service, it’s dismantled, split in half by a hydraulic machine, and then transported by truck, typically to Airbus’ headquarters in Toulouse, France, where it will be integrated into an Airbus A350 XWB.

Each engine completes around 3,000 flight cycles before it requires servicing, efficiently transporting thousands of passengers to their destinations along the way.

So, how does the engine help lift the aircraft off the ground?

McCree describes the engine’s operation with four key actions: suck, squeeze, bang, blow.

First: suck – the front fan draws in air, with 80% of it bypassing the engine and exiting out the back. This generates most of the thrust, propelling the engine forward.

The fan is driven by the core, which uses the remaining 20% of the air, compressing it as it moves through, making it increasingly compact.

"That’s the squeeze phase," explains McCree.

The air mixes with fuel and is ignited, which, of course, is the bang.

The final step? As the compressor decreases in size, the turbine expands, capturing more energy. The air flows through, spinning at each stage.

McCree compares it to blowing on a small windmill at the beach: "It's like a series of stages, each one extracting more and more energy from the airflow."

Feedback from the public.

Rolls-Royce emphasizes that the Trent XWB is not only fuel-efficient but also highly reliable. It boasts a 15% improvement in fuel consumption compared to the original Trent engine.

Additionally, it’s remarkably quiet – despite each of the 68 high-pressure turbine blades producing 800 horsepower at takeoff, which is equivalent to the power of a Formula 1 car.

There are 68 blades, which together generate 50,000 horsepower at takeoff.

The largely unassuming nature of airplane engines means that most airline passengers, unless they’re self-proclaimed aviation enthusiasts, likely give little thought to the complex machinery lifting them into the air.

"Many people board a plane without knowing who manufactures the engine – and often, they don’t even care," says Caroline Day, head of marketing, strategy, and future programs at Rolls-Royce, in an interview with Dinogo Travel.

However, she notes, increasing awareness of the climate crisis is slowly shifting this attitude.

In today’s interconnected world, engine manufacturers can no longer focus solely on aircraft makers and airlines – the average traveler is becoming part of the conversation as well.

More and more travelers are becoming aware of their carbon footprint and are holding airlines accountable for it.

"Thanks to social media, we’re now seeing much more public engagement, which is fantastic," says Day.

"We’re very aware of the pressures from climate change. I like to think we’re proving we’re doing our part," she continues. "We’re focused on using less fuel and cutting down emissions."

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5