Culinary Wisdom from the Spirits of Black Appalachians

A few years back, I was invited to conduct a cooking demonstration in Hindman, Kentucky, at Dumplin’s and Dancin’, a gathering of farmers, dancers, chefs, and food advocates dedicated to preserving Appalachian culinary and musical traditions. They asked me to showcase my grandmother’s chicken and dumplings, Food Network-style. As a writer, my instinct was to simply craft something to read aloud. But the mountain folks were persistent. Feeling anxious, I came prepared with a wealth of history.

I hang a dress that my grandmother had stitched and worn on the kitchen door. Her photograph rests on the prep table as I begin. I lift the heavy stockpot, adding chicken, water, and salt. My grandmother used pieces from a whole chicken; I opt for just the breast. While the chicken simmers, I prepare the dumplings: two cups of self-rising flour, half a cup of shortening, and one cup of milk. I blend the shortening into the flour, then mix in the buttermilk. Flour dusted on the table, I roll out the dough and cut it into one-and-a-half-inch squares with a knife. The steam from the bubbling pot brushes my face. Once the chicken is cooked, I strain the broth, allow the chicken to cool, then shred it. The dough squares go into the boiling broth, and I lower the heat to thicken it all up. Finally, I add the chicken. The tender pieces float in a bowl surrounded by swirls of golden fat and fluffy dumplings. I serve the meal alongside a slice of cornbread and smile at my grandmother’s photograph, seeing her as a kitchen spirit. I thank her for being present.

My grandmother cared for my fevers, kissed my bruises, and nurtured my dreams. She filled her pots and our bellies just as her mother and grandmothers had done for generations. Through slavery, manumission, the Great Depression, wars, poverty, segregation, the Civil Rights Movement, and racism, women of her strength always find a way.

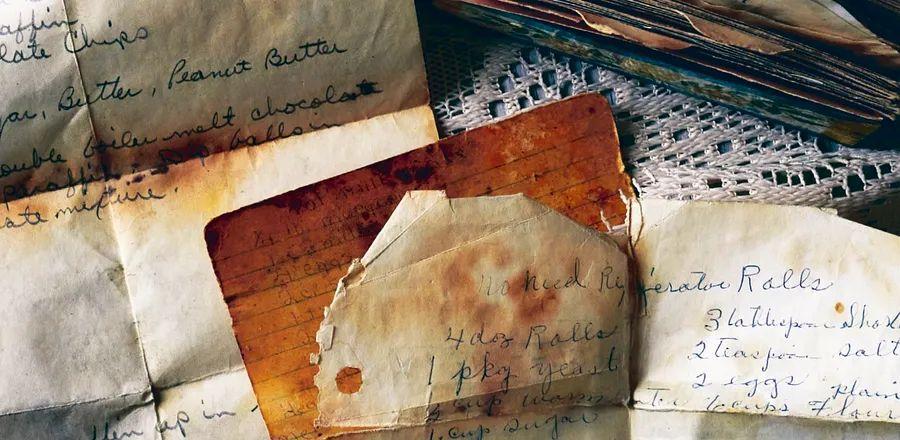

Years ago, when I departed from my grandmother’s home, she loaded my car with food: jars of vibrant red canned tomatoes for soup, paper bags of dried apples for fried pies, treasured recipes, whole cakes, jars of relish, and green beans.

Photos by Kelly Marshall

A jar of green beans she preserved still rests on my counter. I refuse to open it, as it’s the last jar she gave me before her passing. I carefully position the Mason jar within my sight while cooking. I possess some of my grandmother’s pots and serving dishes, welcoming each kitchen spirit with open arms.

I pick up the knife, the spoon, and the apron.

They observe me.

I express my gratitude.

One sweltering night, during a writing retreat in Florida, I woke up in tears. Although she has been gone for over 250 years, I could distinctly hear Grandma Aggy’s voice—urgent and unwavering.

She remarks:

We rested in the kitchen's corner, where the scent of fried meat, copper, and salt filled the air, heavy and humid enough to make me feel ill. In the early hours, before the plantation came alive, I lay drowsily, swatting at gnats near my eyes, drenched in sweat. In those moments teetering between sleep and wakefulness, I heard my mother sing my name, though not in your tongue. Her voice floated through the window like a feather, circling my head like a bird before vanishing into the rafters while I lay in the dark.

We fetch buckets to draw water from the well, empty the slop jars, and collect eggs from the henhouse along with a bit of jowl from the smokehouse. We render fat for both biscuits and soap. We make lye soap from stored ashes and sew a dress for Misses, who desires something fancier, so we send a knapsack with David to deliver to Sally at the Bowmans’ place for alterations. We draw more water, light a fire in the backyard to wash, boil clothes in lye soap, hang them out to dry, fold them, and gather vegetables from the garden. We pick worms off the tobacco before Marse Bowman sends his workers to assist. We milk the cows, churn the butter, feed the chickens, and slop the hogs. Late at night, we harvest beans from our small garden, fry up some hoecakes from our rations, and save a little for ourselves. We cook and share our meals.

We cook. We share our meals. We heal together. I know that the women in my family have been kitchen spirits for generations, watching over our daughters, granddaughters, sons, and grandsons.

Saying:

Just a bit more.

Lower the flame.

Not too much salt.

Please take some; we have more than enough.

I envision myself many years ahead, standing in the kitchens of my great-grandchildren, nodding in approval as they cook, softly whispering, “That’s it. Keep going. There will always be enough for everyone.”

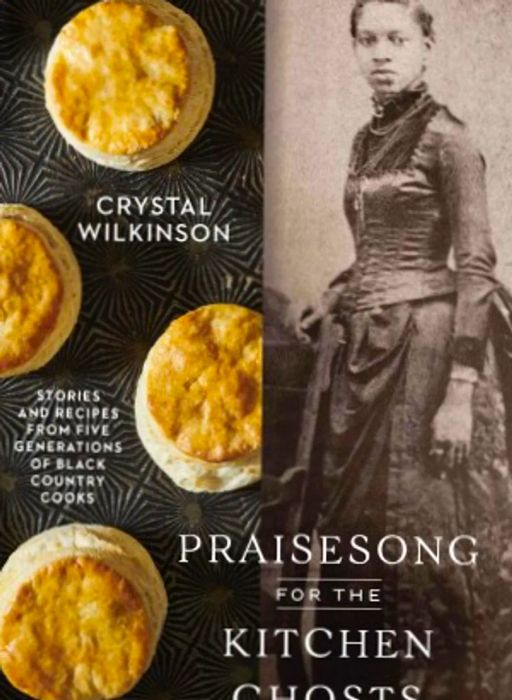

Reprinted with permission from Praisesong for the Kitchen Ghosts: Stories and Recipes from Five Generations of Black Country Cooks by Crystal Wilkinson, copyright 2024. Photographs by Kelly Marshall, copyright 2024. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5