I Joined Scientific Teams Aiming to Preserve Australia’s Great Barrier Reef — Here’s What I Discovered

The Wavelength 4 vessel anchored near Opal Reef in Australia.

Photo: Courtesy of Wavelength Reef Cruises

The Wavelength 4 vessel anchored near Opal Reef in Australia.

Photo: Courtesy of Wavelength Reef CruisesOn a late January day at Opal Reef, roughly 30 miles off Queensland’s northeastern coast, something unusual was happening. I found myself on the deck of a 64-foot catamaran surrounded by plastic tubs fitted with electrodes, filled with live coral fragments, gradually being heated in seawater.

“This is a rapid stress test,” explained John Edmondson, marine biologist and operator of Wavelength Reef Cruises. It’s designed to simulate the warming waters that have caused coral bleaching in this region for years, as part of several ongoing experiments aimed at protecting the Great Barrier Reef from climate change.

I was part of a research team from the University of Technology Sydney on a full-day outing, collecting data and samples from the underwater ecosystems. One scientist focused on how algae photosynthesize and provide nutrients to corals, while another investigated bacteria. Meanwhile, two Ph.D. candidates captured gases released by corals to assess their stress levels, with the scent of sulfur indicating potential issues.

Just 200 feet away from this floating lab, many visitors from another Wavelength vessel were snorkeling and diving on the crescent-shaped reef, learning about conservation from their own team of researchers.

Tourism meets science. This is the modern experience of the Great Barrier Reef, where research and commerce collaborate to seek solutions.

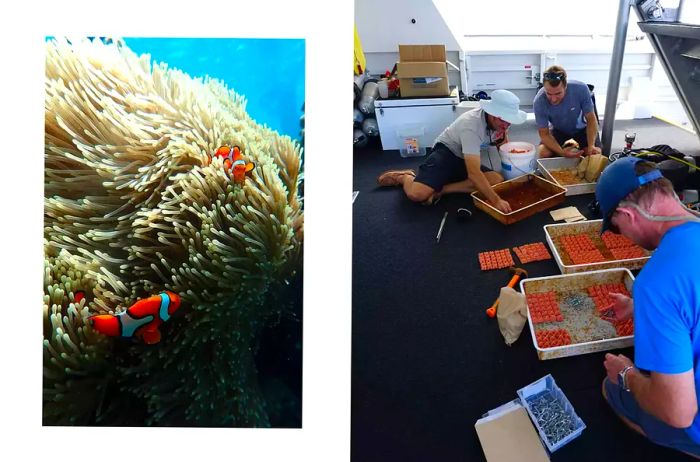

From left: Clownfish swim among sea anemones; the Wavelength 4 crew places larvae onto settlement tiles to monitor reef reproduction.

Courtesy of Wavelength Reef Cruises

From left: Clownfish swim among sea anemones; the Wavelength 4 crew places larvae onto settlement tiles to monitor reef reproduction.

Courtesy of Wavelength Reef CruisesWavelength is one of six commercial operators in the northern reef area between Cairns and Port Douglas participating in the Coral Nurture Program. This initiative brings together scientists and tourism operators who rely on the reef's health for their livelihoods. The program aims to restore marine habitats, primarily using simple masonry nails and Coralclips—stainless-steel devices created by Edmondson and his marine biologist wife, Jenny. They use these to attach coral fragments to damaged reef structures, known in Australia as bommies. The process resembles propagating plant cuttings in a garden, but this garden spans 1,429 miles and includes 3,000 distinct reef systems, numerous hard and soft corals, and around 9,000 marine species.

Since its inception in 2018, the program has successfully planted over 70,000 corals, boasting an impressive survival rate of 85 percent. In November 2021, some of these newly planted corals spawned for the first time. According to Professor David Suggett, who co-founded the Coral Nurture Program alongside Edmondson and fellow UTS professor Emma Camp, a single planted coral fragment can produce hundreds or even thousands of corals throughout its lifetime.

Marine biologist Johnny Gaskell captures images of a coral bed within the Great Barrier Reef.

James Unsworth

Marine biologist Johnny Gaskell captures images of a coral bed within the Great Barrier Reef.

James UnsworthTo protect the reef, scientists must first gain a deeper understanding of it. Since 1998, the reef has experienced five mass bleaching events, resulting in the loss of an astonishing half of its live corals. “Everyone is returning to the fundamentals,” Suggett noted. “We need to comprehend how corals grow and what factors influence their growth—all this crucial data that has been overlooked. Prior to the bleaching events, we didn’t require these tools because the reef was naturally resilient.”

From Cairns, I took a flight to the Whitsunday Islands, located about 300 miles to the south. Marine biologist Johnny Gaskell has been actively involved in planting corals and seeding larvae throughout the archipelago. Many of the reefs surrounding these 74 islands suffered damage from Cyclone Debbie in 2017. Through innovative techniques like 'coral IVF' and larvae management, Gaskell and his team are dedicated to restoring the lost ecosystems.

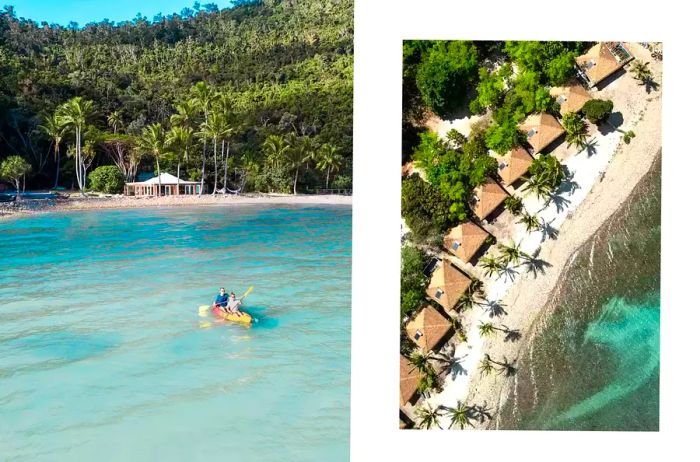

Gaskell and biologist James Unsworth, associated with the eco-friendly tour operator Ocean Rafting, picked me up on an inflatable speedboat from my accommodation, Elysian Retreat—the only carbon-negative resort in the area. This retreat features ten solar-powered cabins nestled along the pristine southern shore of Long Island, serving as a gateway to the Whitsundays.

We raced over to Manta Ray Bay on nearby Hook Island, one of eight designated sites in the Whitsundays where reef restoration efforts are underway. Gaskell highlighted the man-made frames submerged deep below the surface where transplanted corals are gradually repopulating the bay.

From left: Kayaking near Elysian Retreat in the Whitsunday Islands; the ten solar-powered villas boast verandas with beach views.

Courtesy of Elysian Retreat

From left: Kayaking near Elysian Retreat in the Whitsunday Islands; the ten solar-powered villas boast verandas with beach views.

Courtesy of Elysian RetreatWe also visited Daydream Island Resort & Living Reef, a charming low-rise property where Gaskell guided me through some land-based coral nurseries before unveiling the reef itself: a stunning 656-foot stretch of coral that encircles the resort, which he was tasked with designing and establishing as a centerpiece in 2014. This incredible biosphere, subject to the same unpredictable conditions as the ocean, now hosts over 100 fish species and 80 coral species, serving as a vital indicator of the overall health of the Great Barrier Reef.

Nestled within this microcosm is “Steve,” the very first coral Gaskell ever planted. Since then, coral growth has been so abundant that he finds it challenging to locate his protégé amidst the intricate array of sculptural forms. Steve has endured a cyclone, bleaching events, and waves of toxic agricultural runoff brought into the ocean by tropical rains.

“There have been highs and lows — it’s truly been a roller-coaster journey for Steve,” Gaskell remarked with a grin. “He became the test case for coral restoration and then had to weather Cyclone Debbie.” If Steve represents the forefront of the reef’s future, then his thriving condition is promising for us all.

This story originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Dinogo under the headline 'Reef Revival.'

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5