In This Isolated Indian Village, Names Are Sung Instead of Spoken

Phiisha Khongsit, a 39-year-old mother of four, sits in the shade outside her thatch-roof home. Her daughters—ages 14, 10, and 6—play in the yard nearby. As lunch approaches, she gently calls to them with a cheerful five-second melody in a high pitch. After taking a deep breath, she follows with another tune, and then another. Khongsit’s daughters have musical names—and they’re certainly not alone in this practice.

In the secluded, forested village of Kongthong in northeastern India’s Meghalaya state, every inhabitant carries a song for a name. Unlike popular tourist destinations like Uttar Pradesh or Rajasthan, travelers flock to Meghalaya for its natural beauty and rich Indigenous cultures. Those in the know visit Kongthong to witness the tradition of musical names, a custom entirely unique to this village.

Khongsit and the roughly 700 residents of Kongthong belong to the Khāsi community, the largest among the region’s three main ethnic groups. The Khāsi are a matrilineal community, tracing their heritage through their mothers. Together with the Garo and Jaintia groups of Meghalaya, they are among the last in India to maintain this lineage practice. Here, girl children are celebrated, unlike in many parts of India where boys are often preferred.

Kongthong is the only village known to uphold the ancient musical naming tradition of jingrwai iawbei, which translates from Khāsi as “a song sung in honor of the ‘root ancestress’ [founding female ancestor].” In accordance with matrilineal customs and jingrwai iawbei practices, mothers create short melodies that serve as their children’s names. Each name is unique, and once a person passes away, their musical name fades with them. Historically, the community has relied on oral tradition, so the origins of jingrwai iawbei remain uncertain.

Photograph by Paiastar Khongjee

“The jingrwai iawbei tradition has given Kongthong a truly distinctive identity [in the region],” says Dr. Piyashi Dutta, a native of Meghalaya and coauthor of the first written account of the jingrwai iawbei practice. “The term jingrwai iawbei is closely tied to matriliny, reflecting the respect for mothers and the clan’s [founding female ancestor]. Composing the tune and the tune itself serve as ways to honor the founding female ancestor, seek her blessings, and express gratitude for her protection over the clan.”

In the village, both followers of the Indigenous Niam Khāsi religion (a monotheistic belief system embraced by about 85 percent of Kongthong’s population) and Christian residents engage in jingrwai iawbei. Everyone is addressed with a melody—regardless of gender, age, relationship, or social status. Khongsit’s eldest daughter, who is resting in the shade with her mother, demonstrates how she calls to her mom using a tune.

Right after giving birth, each new mother in Kongthong creates a unique melody that becomes her baby’s name. After nine months of pregnancy, mothers experience overwhelming joy upon meeting their newborn, and these feelings are expressed not through words, but through song. “I find it easy to create a tune,” Khongsit smiles, cradling her two-month-old baby boy. “I can do it in just minutes.”

In Kongthong, there are two kinds of melodic names: longer songs lasting 15 to 20 seconds for summoning people from Mytour, such as across a field, and shorter, five-second versions for those nearby. Khongsit demonstrates both the long and short melodies of her children’s names. “The shorter tune functions like a nickname,” notes local guide Phidingstar Khongsit.

Alongside their musical names, children are also given a more formal name, which may be assigned during a Niam Khāsi ceremony known as jer khun or during a Christian baptism, depending on the family's beliefs. Following Khāsi matrilineal customs, the child’s official name is typically selected by the father's mother or occasionally by the father's sister. However, these conventional names are primarily for official purposes, like identification. The jingrwai iawbei serves as the everyday identity for the people of Kongthong, with their melodic names being their lifelong identifiers.

The residents of Kongthong hold the belief that musical names can shield loved ones from malevolent spirits. Therefore, when villagers enter the deep forest to gather food or collect bamboo for building, they rely solely on their musical names, avoiding their conventional names to prevent evil spirits from recognizing them and bringing misfortune.

The jingrwai iawbei tradition of Kongthong has intrigued not only scholars like Dutta but also creatives such as filmmaker Oinam Doren, whose 2016 documentary My Name Is Eeooow is the sole film documenting this practice. In 2017, it earned the Intangible Culture Prize at the 15th RAI Film Festival. “No one in Kongthong shares the same jingrwai iawbei,” Oinam explains. “In that way, they are copyrighted names.”

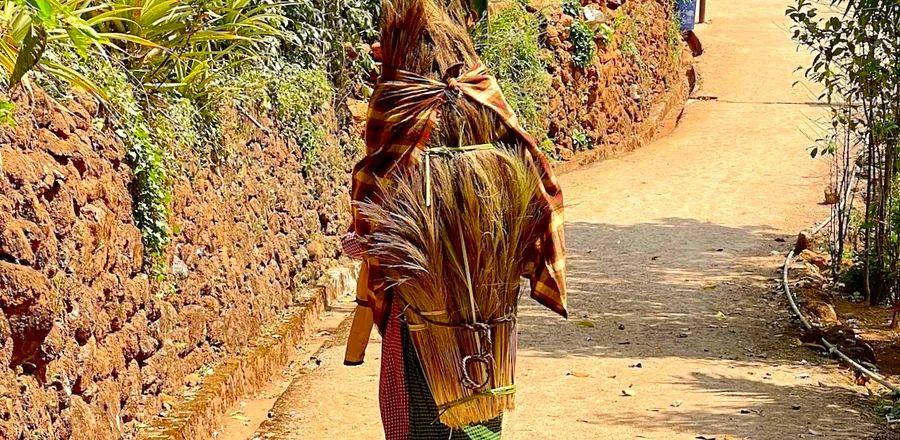

Photo by Anne Pinto-Rodrigues

The 52-minute film highlights the precarious future of the naming tradition, as many young villagers leave Kongthong, which mainly depends on subsistence farming and cultivating a specific grass for brooms, in search of higher education and better job prospects.

“The risk is that oral traditions like jingrwai iawbei might gradually fade away,” cautions Dutta. She believes that if villagers can generate sufficient income to thrive without relocating, the tradition will have a better chance of enduring.

Recent infrastructure improvements, such as new road construction, have enhanced the village’s connectivity and opened up more business opportunities. Additionally, broom grass cultivation has become increasingly popular. Locals craft brooms and sell them to traders from Shillong for around 80 cents per pound. In Khongsit’s yard, fluffy tufts of broom grass are spread out to dry in the sunlight. As awareness of jingrwai iawbei grows, tourism is also increasing, providing additional income to residents. The Indigenous Agro Tourism Co-operative Society organizes village tours and can be contacted through its Facebook page, with tours starting at approximately $7 per person.

As the people of Kongthong become more influenced by mainstream Indian culture, the jingrwai iawbei tradition is evolving. Recently, one woman named her child after a popular Bollywood song from the romantic action movie Kaho Naa . . . Pyaar Hai (2000). Oinam, however, is not taken aback and maintains a pragmatic view of this change. “Cultures and traditions aren’t museum pieces,” he asserts. “They’re not fixed. They will naturally evolve over time.”

For now, the air in Kongthong resonates with the sweet sounds of musical calls as villagers reach out to their loved ones. However, on Khongsit’s front porch, the atmosphere is serene and still as she gently holds her sleeping baby boy in her arms.

Evaluation :

5/5