The hidden, ancient wonders beneath Turkey's surface are nothing short of extraordinary.

Rich in ancient marvels, Turkey, positioned at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, has been a pivotal hub for many great empires. These empires have left behind archaeological gems that rival the country's stunning natural beauty.

However, not all of Turkey’s treasures are visible, basking in the warm sunlight above ground.

Equally captivating, yet often overlooked, are the underground historical relics, some dating back over 12,000 years, waiting to be discovered.

Some of these hidden sites are well-known, such as the Basilica Cistern in Istanbul. This Roman-era underground reservoir has been open to tourists for decades and even made an appearance in the iconic James Bond film, “From Russia with Love.”

Some may not be as widely recognized, but they are equally awe-inspiring and intriguing.

Here are some of Turkey’s most remarkable underground wonders awaiting exploration:

Şerefiye Underground Cistern (Theodosius Cistern), Faith, Istanbul

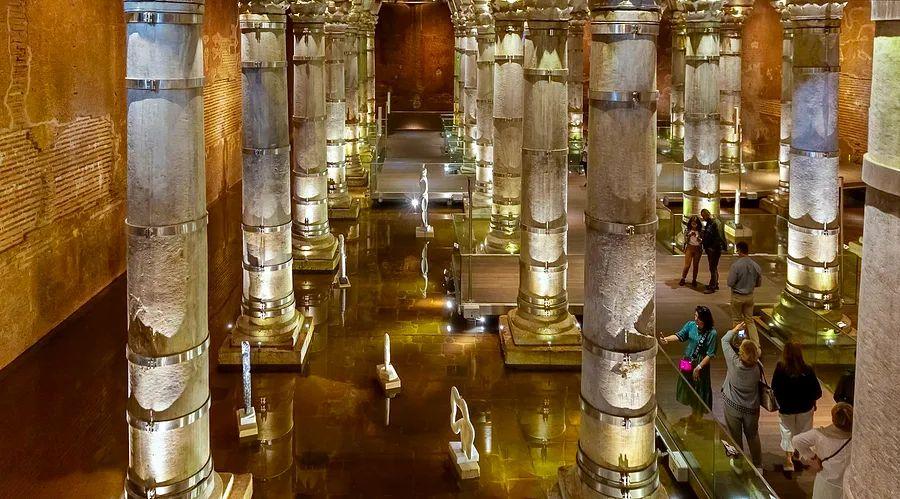

Much like the Basilica Cistern, this graceful underground reservoir was constructed during the late Roman era to secure water supply for Constantinople, the ancient name for Istanbul.

In contrast to the Basilica, this hidden chamber lay forgotten for centuries, only rediscovered less than 15 years ago.

The Şerefiye Cistern was built during the reign of Theodosius II, the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Emperor who ruled from 402 to 450 CE. Today, it lies in Istanbul's Fatih district.

Its purpose was to store fresh water transported from the Belgrade Forest, located north of Istanbul near the Black Sea. This water was carried through a 155-mile canal system, including the ancient Aqueduct of Valens, which still stands in Fatih, before being distributed to the city's residents.

Spanning 82 by 147 feet (25 by 45 meters) with a ceiling nearly 36 feet high, and featuring walls eight feet thick and 32 marble columns, the structure—also known as the Theodosius Cistern—is as grand in scale as it is in beauty.

However, sometime around the late 18th or early 19th century, the cistern was forgotten after a large private estate was constructed on the site, causing it to remain concealed for many years.

The municipality of Istanbul took control of the site in the early 20th century, but it wasn't until 2010, when some modern additions were removed, that the cistern's underground entrance was rediscovered.

This 1,600-year-old water reservoir opened its doors to the public in 2018. Inside, columns adorned with Corinthian capitals gleam with brilliance, while polished brass rings reflect the colors and movements of various cultural events and installations.

Upon entering the cistern, the thick, protective walls create a cocoon, shutting out the noise of the outside world. The sounds of bustling streets are replaced by the soothing, rhythmic flow of water.

Dara Cisterns, Mardin

When archaeological work began in Dara in 1986, it was a modest settlement situated on a windswept, verdant plain about 19 miles (30 kilometers) from the historic city of Mardin in southeastern Turkey.

Aside from local herders guiding their livestock through the ruins of this 6th-century garrison town, few ventured to the area.

Today, the site has revealed a wealth of treasures, including rock-cut tombs, an olive processing workshop, and a network of underground cisterns.

One of the cisterns is so vast that locals once believed it to be a zindan, or dungeon, and wove elaborate stories of prisoners chained in the dark, relying on fleeting rays of sunlight to track the passing days.

In truth, the cisterns served a more practical purpose, storing water brought down from the surrounding mountains to supply both the local population and Roman soldiers stationed in Dara.

Derinkuyu, Nevşehir, Cappadocia

In 1963, a Turkish farmer noticed that his chickens mysteriously disappeared and then reappeared. Curious to uncover the cause, he followed their tracks to a crack in the tufa rock, the same volcanic material that forms Cappadocia’s famous peribaca fairy chimneys, and stumbled upon an entrance to an 18-story-deep underground cave system.

Derinkuyu, which translates to “the deep well” in English, was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1985. It once served as a refuge for up to 20,000 people, and today, visitors can walk the same paths that early Christians used to escape Arab invaders centuries ago.

Although fresh air flows through deep ventilation shafts, the atmosphere inside Derinkuyu is thick and becomes more humid as you descend 328 feet (100 meters).

At times, the narrow path forces visitors to duck under low-hanging rocks, twisting in unexpected directions. The muffled sounds of voices reverberate off the stone walls, while shadowy figures of fellow explorers emerge in the dim light.

Exploring the eight floors open to the public, visitors encounter remnants of churches, stables, wine presses, and abandoned tombs, where the past seamlessly blends with the present.

Rümeli Han Tunnel, Taksim, Istanbul

The stately buildings that line Istanbul’s bustling Istiklal Caddesi once sheltered corset-makers, carpet vendors, and exclusive clubs frequented by émigrés who had fled revolutionary Russia.

In grand venues like Rümeli Han, Istanbul’s elite gathered to dine, while artists, actors, and singers graced the stage. Whether they made use of the hidden tunnels beneath the building, which remained concealed until their discovery in 2017, remains a mystery.

Rümeli Han was constructed in 1894 for Sarıcazade Ragıp Pasha, the chief steward of Sultan Abdülhamid II. Renovation work that began just over five years ago uncovered the building’s long-hidden underground passages.

The tunnel is now accessible to the public, with a simple sign taped to the elegant marble facade of the building, quietly announcing its existence.

Inside, tightly packed ochre-colored clay bricks shut out the world above. Windowless chambers, placed at regular intervals along the walls, lead from one to the next, eventually reaching stairwells—now locked—that once connected to the street above.

The exact purpose of the tunnels remains unclear. Perhaps they served as a hidden route for the city's elite, allowing them to move unnoticed between secret meetings and clandestine encounters.

Sancaklar Mosque, Büyükçekmece, Istanbul

From a distance, all that is visible of the post-modern Sancaklar Mosque are its solid grey dry stone walls and a rectangular minaret towering above. The mosque sits in a secluded suburb on the outskirts of Istanbul.

Beneath the surface, however, lies something that seems entirely out of this world.

Externally, the mosque appears as a fusion of past and future. Sparse vegetation sways gently in the breeze, while in the distance, pragmatic apartment blocks line the horizon. The dry stone walls evoke the feel of a traditional farm, while the pattern of parallel lines running down the gentle slope resembles that of ancient archaeological sites.

Inside, the space is serene and womb-like. The only adornments are the raw stone masonry and thick slabs of reinforced concrete, creating a minimalist atmosphere of calm.

This is a unique and striking space. Every seat in the building’s amphitheater offers a direct view of the mihrab, the part of the mosque that indicates the direction of Mecca. Here, instead of a traditional intricately carved niche, the mihrab is symbolized by a single beam of light.

In contrast to traditional mosque designs, Sancaklar lacks a central dome or any dome at all. Above, a smooth expanse of concrete arches, designed in the style of a Zen garden, enhances the tranquil atmosphere.

Sancaklar Mosque is both awe-inspiring and imposing. Completed in 2012, it embodies the ongoing tension between the manmade and the natural, symbolizing our place within that balance.

Göbeklitepe, Şanlıurfa

A futuristic dome sits just outside Şanlıurfa in southeastern Turkey, contrasting sharply with the natural beauty of the rolling hills around it. From an archaeological perspective, what it shelters is even more unsettling.

Inside the dome, visitors look down upon massive stone stele – T-shaped pillars weighing about five tons each, etched with carvings of wild animals along their sides.

These stone structures date back to the pre-Pottery Neolithic period, around 9600-8200 BCE. In 2018, UNESCO recognized Göbeklitepe as the earliest known example of monumental human architecture. By comparison, Stonehenge, with its construction between 3000-2500 BCE, now seems almost juvenile.

Beyond its age, the discovery of this ancient sanctuary in 1994 revolutionized archaeology. Scholars believe the T-shaped pillars were erected by hunter-gatherers as a place of worship, a concept once thought to be exclusive to settled agricultural societies.

When viewed in their original setting, it’s difficult to imagine how these enormous stones were ever transported and positioned by human hands, or by any means.

To truly appreciate the scale and grandeur of Göbeklitepe and to understand the effort behind its creation, a visit to the full-scale replica in the Şanlıurfa Archaeology Museum is highly recommended.

Yeraltı Camii, Karaköy, Istanbul

Tucked away between buildings near the entrance to the Golden Horn, the Yeraltı Mosque in Karaköy, Istanbul, is easy to miss. A humble door leads into a minimalist interior where repetition and clean lines dominate the design.

Inside, 42 low-set piers are arranged in parallel rows. Even on the hottest days, the space remains refreshingly cool, thanks to seven-foot-thick walls and the chill rising from the red carpet underfoot.

A strange green glow emanates from the far end, but at first glance, this mosque might not appear to hold much intrigue.

Appearances can be deceiving.

Yeraltı, meaning 'underground,' was originally a dungeon situated in the basement of a fort built by the Byzantines in the 8th century CE.

It also served as the northern anchor for a massive chain that stretched across to Istanbul’s Topkapı Palace—once the heart of the Ottoman Empire—on the opposite shore. This chain was intended to prevent enemy ships from reaching the city, but like many ambitious plans, it failed, ultimately allowing Fatih Sultan Mehmet to conquer the city in 1453.

Over the centuries, the fort suffered damage, was repurposed, and eventually transformed into a mosque in 1757 by Grand Vizier Bahir Mustafa Paşa.

And that strange glow? In 1640, a Nakşibendi dervish dreamt that the bodies of two Arab soldiers, believed to have been involved in the failed 7th-century siege of Constantinople, were buried here.

During Ramadan, it’s customary for people to visit and pray at their graves, which are illuminated by bright neon lights, adding an unexpectedly festive atmosphere to this normally serene mosque.

Evaluation :

5/5