The Significance of Chinatown to America—and to Me

This piece is part of Dinogo, A Retrospective. In honor of Dinogo's 15-year anniversary, our editors and cofounders have chosen this story as one of our top 15 favorites. We hope you find it as enjoyable as we do.

Manhattan’s Chinatown is my hometown. Forty-five years ago, I drifted through my baptism at the historic Transfiguration Church on Mott Street, a place where countless Chinese and other immigrant families have marked new beginnings with vibrant weddings and solemn farewells with funerals. My family isn’t religious, so I believe the baptism was more about blessing my connection to the neighborhood than to any divine figure. Chinatown is where my grandmother toiled as a seamstress and my grandfather worked in a fortune cookie factory. Even during elementary school on Long Island, my brother and I wore outfits she crafted and enjoyed cookies he folded in our lunches.

Most Sundays, we would immerse ourselves in the bustling crowd on our way to the small apartment on Madison Street that our grandparents shared with three other relatives. Through the eyes of children during these family visits, we marveled at precarious fruit stands, toy bins, and fishy puddles; loving hands would pinch our cheeks and reward us with tangy fruit candy. Chinatown was our space to embrace our Chinese identity, a contrast to our daily life surrounded mostly by white classmates. Our upbringing was sharply divided. As a budding writer in the East Village, I sought a different lifestyle. I began to frequent Chinatown for everyday needs—language classes, fresh produce, and delicious steamed buns—and for deeper reasons, to forge a connection to something larger than myself. Growing up as a Chinese American in Long Island, I often felt out of place. In Chinatown, I blended in unless I chose to stand out, and I started to realize that this sense of physical comfort and anonymity is a privilege. Visiting Chinatown gave me a glimpse of belonging, as I yearned to better understand my family's journey and the significance of this place to them.

Chinatown emerged from diaspora but also embodies the universal human desire to gather and create a home. It’s the quintessential American story.

Over a decade ago, I authored a book, American Chinatown (Simon & Schuster), exploring five of the most notable Chinatowns in the U.S., including the oldest in San Francisco, where I had just relocated. I spent time with the late historian and architect Phil Choy, who showed me how to interpret the unique, pagoda-roofed skyline as a narrative of Chinese American resilience and self-creation post the 1906 earthquake. I engaged with passionate teens reclaiming their heritage through vibrant lion dance troupes and neighborhood tours. I also met new arrivals, whose open hearts and minds embraced new possibilities. As they adjusted to their new lives, I learned alongside them. Regardless of their backgrounds, the people I spoke with shared tales of hardships, yet there was a prevailing thread of optimism in the journeys that brought them here.

Photo by Alex Lau; illustration by Xinmei Liu

Recent years have left many Americans reeling from the fragility of our sense of belonging. The rise in anti-Asian hate crimes and harassment nationwide has made my older relatives hesitant to go out alone, even in places that once felt like home. Many beloved mom-and-pop shops in Chinatown have closed down; those still operating now shut their doors earlier to ensure their safety before nightfall. I never imagined my friends and I would be discussing how to protect ourselves on public transit or while walking alone at night. Lately, I've been reflecting on how fear and racism were foundational to the creation of the first Chinatowns. It’s the parallel story we often avoid, a troubling but intrinsic aspect of the immigrant experience that is just as American as the dream itself.

Recently, I guest-lectured a class of Stanford University medical students on Asian American history, racism, and public health. I was constantly reminded of the significance of language: When a cholera epidemic struck New York City in 1832, the Board of Health labeled it “the Oriental cholera.” Later in the century, Chinatown was depicted as the abode of “an inferior race” rife with “foul vapors.” Chinese women were barred from entering the country, labeled as “prostitutes,” “dirty,” and “morally corrupt,” yet at the same time, they were exoticized and exploited by white men.

This ongoing sense of otherness connects directly to the term “the China virus.” Visitors have always flocked to Chinatown for its mix of the seemingly exotic yet familiar, whether it’s savoring dim sum, hearing another language, or admiring the pagoda rooftops. This perpetual foreignness poses a challenge. Following the tragic Atlanta spa shootings that claimed the lives of six Asian women, journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones tweeted that “anti-Asian & anti-Black racism and violence run in tandem,” emerging from a society “where nationalism has been reignited and normalized.” She emphasized that both groups were brought to the U.S. for labor with no intention of granting them full and equal citizenship alongside white individuals.

Photo by Alex Lau; illustration by Xinmei Liu

Chinatown embodies a place of contradictions. It functions as both a scapegoat and a sanctuary. The original Chinatowns were ghettos for male Chinese laborers, who lived among but apart from whites, while Chinese women were denied entry to prevent the formation of families. Yet a Chinatown like San Francisco’s is now recognized as a historic neighborhood, a gateway, a representation of the American dream realized. Many Chinatowns have been diminishing over the years due to gentrification and continue to rely on a volatile tourism market. The ongoing questions about the significance of Chinatown—its value and how to protect its future—are familiar, but have become more pressing in light of the pandemic.

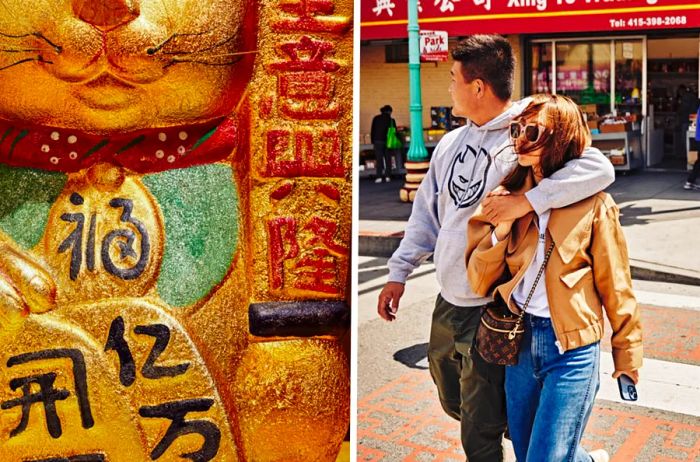

One sunny spring afternoon, I took a stroll through San Francisco’s Chinatown. I hadn’t visited the area much in the past two years—hardly going anywhere at all—and the familiar vibrancy of life in Portsmouth Square, one of my favorite spots for people-watching, was reassuring: children laughing on the play structures while caregivers chatted on the benches; elders making their rounds with their hands folded behind them. A few blocks away on Waverly Place, one of the oldest lanes in the neighborhood, I stopped by to see chef Brandon Jew. His restaurant, the Michelin-starred Mister Jiu’s, is only the third business to inhabit the 10,000-square-foot space at 28 Waverly Place, following the iconic Four Seas restaurant, where he recalls attending his uncle’s wedding banquet in the upstairs hall. (The restaurant's name is a reclamation, correcting the misspelling of his family’s name upon their arrival in America.)

Two men stood leisurely smoking in the alley as music drifted from beneath the eaves of the Eng Family Benevolent Association. Outside the restaurant, vibrant painted goldfish swam along the sidewalk, which had reopened in January for a four-day-a-week service. Jew launched Mister Jiu’s in 2016, celebrated for its inventive, carefully crafted Chinese American dishes that showcase seasonal local ingredients, after honing his skills in esteemed California kitchens like Zuni Café and Quince. At this year’s James Beard Awards, he received accolades for best chef in California and best restaurant cookbook for Mister Jiu’s in Chinatown (Ten Speed Press), coauthored with Tienlon Ho. Raised in San Francisco, Jew has deep ties to Chinatown, where he participated in Chinese New Year festivities with his kung fu class as a child.

“What draws Chinese Americans back to this neighborhood is the fact that this was our origin,” Jew shared, while his six-month-old son, Bo, who had just started crawling, made his way toward me. We conversed in the dining area, which overlooks Grant Avenue and the sun-bleached peak of the iconic Transamerica Pyramid. Directly across the street lies the Wok Shop, a cherished kitchen supply store run by Tane Chan, who has been selling Chinese cookware since 1972.

Photos by Alex Lau

Outside, Chinatown still seemed quiet. Yet behind this seemingly dormant façade, renewal was evident. Jew highlighted the newly renovated playground that had reopened across the street; the upcoming $66 million redesign of Portsmouth Square by the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department; and the anticipated September launch of the Central Subway, an underground light rail that will connect Chinatown to the neighborhoods south of Market Street. He noted that this physical and civic investment in the community indicated much-needed support during a time of despair, symbolizing hope.

For Jew, the attacks on Asians in Chinatown and across the Bay Area during the pandemic reinforced his dedication to the community and deepened his awareness of racial injustice. The perseverance of his neighbors motivated him to continue operating Mister Jiu’s and instilled in him a profound sense of responsibility toward the elders who had supported him.

Being reminded of what that older generation went through, in this time of renewed hate, it helps shape your understanding of yourself. And that you deserve a place.

“There is strength in this community,” Jew remarked. At 42, he belongs to a generation that had thought public hostility was a thing of the past, especially living in the Bay Area, which has a rich Asian American history dating back to the mid-1800s. The violence directed at Asian seniors left him shocked, prompting him to urgently advocate for Chinatown on social media and beyond, raising awareness against AAPI hate. The restaurant organized fundraisers to support Cut Fruit Collective and the Chinatown Community Development Center. “Remembering the struggles of the older generation during this time of renewed hate helps you understand your own identity. It reminds you that you deserve a place,” he reflected. “That matters.”

Conversations with Jew made me yearn for the familiar rhythms of my own Chinatown, prompting a trip to New York City. For the past few years, I had been exchanging thoughts on the neighborhood’s condition with Grace Young, the James Beard Award-winning author and culinary historian. Having lived in New York for over 40 years, she began visiting Chinatown daily in January 2020 to check on establishments like Hop Lee, a restaurant that has long served a working-class clientele of veterans, postal workers, and local teachers from P.S.1. She has maintained this routine ever since. “The immediate rejection of Chinatown drained the life out of the neighborhood,” she told me. Restaurants and markets were deserted, and street vendors lost their customers. In the pandemic’s initial three months, businesses in Chinatown experienced revenue declines of up to 80 percent. By March 2022, nearly a quarter of the ground-floor storefronts in New York’s Chinatown were vacant.

A petite, birdlike woman with glasses and a warm smile, Young, 66, had always considered herself a reserved individual. However, witnessing the struggles of low-income immigrants, workers, and business owners fighting for survival transformed her into an activist. “I never imagined losing Chinatown was even a possibility,” she expressed. She refused to stand idly by and let it happen.

Young discovered her voice as a passionate advocate, launching a video series titled “Coronavirus: Chinatown Stories” to highlight the economic struggles of Chinatown residents. She collaborated with nonprofits like Asian Americans for Equality and Welcome to Chinatown to fundraise for the community and initiated social media campaigns with the James Beard Foundation, including #LoveAAPI and #SaveChineseRestaurants. “I want people to express their support through love,” Young told me one afternoon while we navigated around weekend visitors on Canal Street. Though the crowds hadn’t returned to pre-pandemic levels, their presence was uplifting. “All these people come here for the food and to honor those who maintain these cherished traditions. In challenging times, everyone can show their support by being visible with that love.”

People in Chinatown perhaps understand better than most what it means to look out for one another.

Her humanitarian initiatives have garnered recognition and funding from the James Beard and Julia Child foundations; the former commended Young’s “efforts to preserve America’s Chinatowns in the face of Asian American and Pacific Islander hate,” while the latter recognized her “significant contributions to maintaining and sharing Chinese culinary traditions.” The acknowledgment from these historically white institutions felt significant: Chinatown mattered to them as well. “I don’t have any grand vision for the future,” Young said, as we sat on a bench in Columbus Park, observing seniors engaged in card games and young people playing basketball nearby. We shared stories about our families and highlighted special places: a favorite eatery here, a cherished shop there. “But I respond to what resonates with me: Chinatown narrates the story of America.”

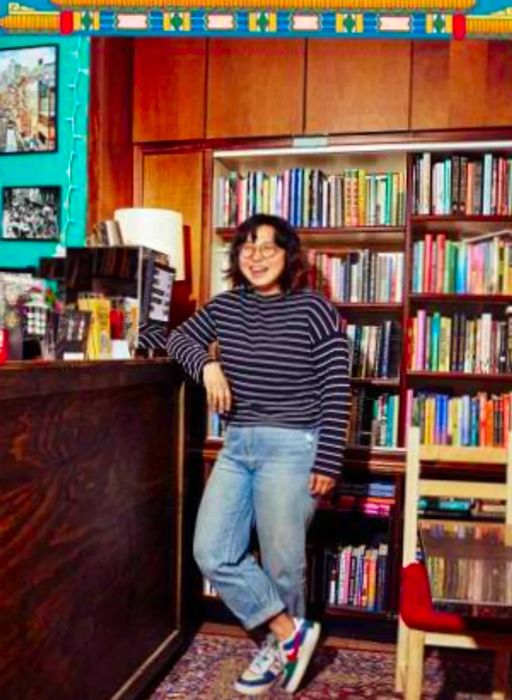

The rich history of Chinatown and the Asian American resistance movement rooted there serve as a significant foundation for Lucy Yu. In December 2021, she opened Yu and Me Books, a charming bookshop and café adorned with string lights on the east side of Columbus Park, located among Chinatown’s funeral parlor row. Six months into what had been a whirlwind for her business, I sat with Yu, 27, as she engaged with customers and prepared coffee drinks from her espresso machine. Behind her, a vibrant aquamarine wall showcased framed prints, paintings, and photographs by the late Corky Lee, a pioneering photojournalist who began documenting Chinatown and Asian American life and activism in the 1970s.

Photo by Alex Lau; illustration by Xinmei Liu

Before opening her bookstore, Yu worked as a chemical engineer and then as a supply chain manager. “It was a personal dream of mine,” she shared. “I was pleasantly surprised to find it resonated with so many. My neighbor’s grandparents visited and said, ‘I grew up on this block. I’ve never seen anything like this here, and I’m so glad you’re here.’ That means the world to me.”

Part of her mission is to foster comfort and community. In mid-March, just a month after Christina Yuna Lee was murdered in her Chinatown apartment nearby, the bookstore hosted an event distributing free pepper spray and personal alarms provided by the nonprofit Soar Over Hate. A thousand attendees showed up, with some waiting for two hours. Brooklyn artist Leanne Gan created art for those who came. In a time of trauma and grief, the community was seeking healing together.

“I often joke that I’m three kids in a trench coat,” Yu laughed. “I have no idea what I’m doing.” But she’s courageous enough to ask herself, What would make me feel safer? Pepper spray: sure. A sense of community: absolutely. And enjoying drinks and dumplings with friends and neighbors in Chinatown? Always a great idea.

The writer Charles Yu shared with me that when it comes to place, “we all inhabit a blend of emotional feelings, ideas, and mental assumptions,” whether we are aware of it or not. “This resonates particularly strongly with Chinatown.” His novel Interior Chinatown (Vintage), which won the 2020 National Book Award, explores the evolving mythology of the neighborhood and its inhabitants, exposing stereotypes that diminish Asian lives. Yu noted that the writing of the book was shaped by his shifting perspective on his parents’ immigration story following President Donald Trump’s election. Fifty years into their American journey, the nation returned to discussions about who belongs and who doesn’t. Everything was seen through a new lens.

Yu challenges stereotypes by portraying individuals with rich inner lives filled with fears, regrets, and aspirations. In Interior Chinatown, we meet Willis Wu, who resides in a cramped one-room apartment in Chinatown and aspires to be Kung Fu Guy—a role that offers him the highest respect available for someone like him. This serves as sharp, satirical commentary, but the real tragedy is what he has yet to grasp: he can be a leading man, fully realized and steering his own narrative. He can be more than just a background character.

In many ways, Yu remarked, imagination fuels our hopes. The deeply rooted American belief that hard work leads to success and a sense of belonging has always inspired Chinatown. However, the Asian American community, both within and beyond the neighborhood, now feels increasingly uncertain about its place and safety. This realization carries a harsh weight. Nevertheless, I still uphold the vision of Chinatown as a land brimming with possibilities—imbued with both fear and hope. It deserves recognition in its full humanity, just as we do.

Photos by Alex Lau

What does Chinatown signify for me, years after my initial encounter? I remain passionately driven to stand in solidarity with the community and its meaning: We exist. We’ve always existed. It’s about claiming our identity as Americans and advocating for that right, even when it feels uncomfortable and frightening. Though it’s been a while since I engaged daily with Chinatown, connecting with some of the most vocal advocates in the area has rekindled a sense of faith within me. Perhaps better than many, the people of Chinatown understand what it means to support one another. The path through these challenging and divisive times remains uncertain. Yet maybe it’s reassuring to know we’re navigating this together, even if we’re stumbling along the way.

Evaluation :

5/5